How Nintendo Reinvented Zelda for Breath of the Wild

Breath of the Wild feels different than any other Zelda game, but the puzzle-solving that put the series on the map is still at its core.

SAN FRANCISCO – The Legend of Zelda franchise dates back more than 30 years, and its latest installment is finally here. If you guessed that keeping an aging franchise feeling fresh and inventive is tough, well, you guessed right.

Breath of the Wild (launching March 3 for Nintendo Switch and Wii U) feels different than any Zelda game that came before it, but the logical puzzle-solving that put the series on the map is still at Breath of the Wild’s core, as three of its developers revealed.

I attended a panel at GDC 2017 entitled “Change and Constant: Breaking Conventions with The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.” Designer Hidemaro Fujibayashi, technical director Takuhiro Dohta and artist Satoru Takizawa all gave their input, and revealed their behind-the-scenes tips and tricks that helped make Breath of the Wild feel modern without compromising any classic Zelda paradigms.

To make a new Zelda game, the team had to channel the franchise’s past while finding new ways to keep it fresh.

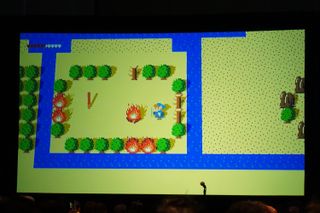

Fujibayashi spoke first, explaining a process he called “multiplicative gameplay.” He showed a screenshot that looked very much like the first Legend of Zelda game on the NES, save that Link was decked out in blue rather than green, and a few unfamiliar items were scattered across the stage. To pitch the game, Fujibayashi created this 2D prototype, in which he could shake trees with the wind, roll logs into the river, and shoot arrows through flames to create fire arrows.

MORE: Critics Going Crazy Over Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

Breath of the Wild, in full 3D, works largely the same way. Rather than invest tons of resources in making hundreds of small, unique puzzles, Fujibayashi instead gave players a toolbox to apply to the whole world as they see fit. Players can bake fruit with torches, roll boulders downhill to crush enemies, or toss foes’ projectiles right back at them. Multiplicative gameplay lets players devise their own ingenious solutions, while still forcing them to think logically.

Dohta spoke next, and gave something akin to a science lecture. He discussed two distinctive systems that appear in Breath of the Wild: a physics engine, which is a necessity for any action game, and a chemistry engine, which sounds much less familiar. Game physics, Dohta explained, are about telling “clever lies” to the player to make in-game physics controllable, responsive, optimized and (somewhat) realistic.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

For example: In Breath of the Wild, Link can freeze objects with the Stasis skill. If he then hits the object repeatedly, it will go flying when unfrozen. Even in Hyrule, the law of Conservation of Energy still applies.

A chemistry engine, on the other hand, is a term that doesn’t often come up in games development. Dohta described it as a system that affects the “state” of objects in-game rather than their movement. Fire, water, and ice are “elements” whereas trees, rocks, characters and weapons are “materials. Breath of the Wild features a chemistry engine that dictates what happens between elements and elements, elements and materials, and materials and materials.

This could result in chaining metal blocks together for an electric shock, or lighting a stick on fire. This kind of common-sense approach to design, Dohta said, is what helps players solve puzzles based on what they know to be true in real life.

MORE: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild - Switch or Wii U?

Finally, Takizawa discussed the challenges of creating an art style to fit the game. Wind Waker looked very cartoony; Twilight Princess looked more realistic; Skyward Sword was bright and colorful. Each art style helped determine not only the game’s overall tone, but player expectations as well. Gamers might expect different physics in Wind Waker than Twilight Princess, and that would affect how they approached puzzle-solving in the world.

Takizawa explained that the perfect art style for a game made it “easy to lie.” In Breath of the Wild, he tried to balance playability and reality. A fantasy adventure game can’t strive for perfect realism, he explained, because it would interfere with how the game’s weapons and magic feel.

On the other hand, players still need a modicum of realism to balance out pure playability, otherwise they have no idea what the constraints of the setting are. The art style for Breath of the Wild, said Takizawa, should be “refreshing and full-flavored,” like a Japanese beer. (Dohta, too, initially came up with the chemistry engine while drinking Japanese beer, so perhaps the old ways really do work best.)

The main thrust of the panel wasn’t shocking: To make a new Zelda game, the team had to channel the franchise’s past while finding new ways to keep it fresh. Still, for Zelda fans – particularly those who are interested in game development themselves – the discussion provided plenty of food for thought, and a substantive glimpse into the process behind one of gaming’s best-known series. Breath of the Wild will launch on March 3 for the Nintendo Switch and Wii U, and cost $60.

Marshall Honorof is a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.