Net Neutrality Won't Save the Internet. Competition Will

Breaking up broadband monopolies to provide real competition, not net neutrality regulations, will give Americans faster, cheaper broadband.

Judging by what you might have read online, you'd think the world was about to end with the imminent rollback of existing net neutrality rules, due for a vote by the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) on Dec. 14.

The reversal would give "major corporations — like Verizon and Comcast — the power to block mobile apps, slow websites and even control which news outlets we can access," according to the ACLU.

"Comcast, Verizon and AT&T ... want to gut FCC rules and then pass bad legislation that allows extra fees, throttling & censorship," said the digital-activist group Fight for the Future.

The rule change "paves the way for an internet that works more like cable television, where wealthy insiders decide which speakers can reach a broad audience," warned the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Oh please. I oppose the FCC's proposal to reserve its 2015 decision reclassifying broadband as a utility, but the major internet service providers (ISPs) are not likely to change the way they do business as a result. They make tons of money under the existing rules, and they also made plenty of money before the rules were changed.

"If the internet was not a terrible dystopia in 2014, there's not a ton of reasons to think that companies are going to do any of these awful things that they didn't seem to have any reason to do before," said Julian Sanchez, an analyst with the libertarian Cato Institute, on Wisconsin Public Radio last month.

MORE: What Is Net Neutrality?

Instead of getting angry about net neutrality, we should be outraged that we Americans pay more for broadband and have slower speeds than consumers in almost every other developed country.

We should demand that the government force the major broadband ISPs (mostly, cable-TV companies) to open up their last-mile networks (the physical connections between customers' homes and ISP facilities) to competition — to "unbundle local loops," in industry parlance.

But such forced unbundling is unlikely to happen in the current political climate. The cable ISPs will fight such action tooth and nail, as it completely undermines their business model.

"We should be outraged that we pay more for broadband and have slower speeds than consumers in almost every other developed country."

So, as an imperfect substitute for local-loop unbundling, we can instead choose to let Verizon, AT&T, Google and other companies roll out technologies such as VDSL, satellite broadband and 5G fixed-wireless broadband to compete with the cable companies. Such moves are already underway, and they've even got support in Congress. They deserve our support.

Why I'm neutral about net neutrality

The quest for net neutrality is a well-intentioned distraction, a palliative half-measure aimed at preventing the stagnant U.S. broadband market from getting worse. It won't get us what we really need: faster speed and lower prices.

No one can agree on what net neutrality exactly means. Are "fast lanes" allowed? Can companies "throttle" bandwidth-hogging consumers? It's like arguing about the shape of a cloud — people make it look like whatever they want to see.

Tim Wu, the Columbia law professor who came up with the phrase "net neutrality" 15 years ago while he was at the University of Virginia, wrote in his paper introducing the concept that "broadband carriers should not be allowed to discriminate in how they treat traffic on their broadband network."

Most proponents (and opponents) of net neutrality would agree. But there's more.

Wu's entire sentence for the above quotation: "Absent evidence of harm to the local network or the interests of other users, broadband carriers should not be allowed to discriminate in how they treat traffic on their broadband network on the basis of internetwork criteria."

The first clause means that broadband ISPs should be able to throttle bandwidth hogs. If a customer needs more bandwidth, Wu argued in 2002, the customer can pay for more. Many of today's net-neutrality advocates might be disappointed with that interpretation.

"The bright line between the open internet and the local ISP networks has been washed away."

The second clause — "on the basis of internetwork criteria" — is even more relevant today than when Wu wrote it.

In his paper, Wu drew a bright line between the open internet and the local, "last-mile" networks that broadband operators own and control. Broadband ISPs should "police what they own," Wu said, but they should not discriminate among the many forms and sources of content passing through their local networks on the way to consumers.

Fifteen years out of date

The problem is that, in 2017, the bright line between the open internet and the local ISP networks has been washed away. Today, Facebook, Netflix, Google and other large online content providers can bypass the open internet to get data more quickly to your ISP — and to you.

They can connect their own networks directly to your ISP's local network in a procedure known as "peering." They can also use a "content-delivery network," or CDN, to place servers caching their content geographically close to, or even within, your ISP's local network.

When I watch a movie on Netflix, the video stream doesn't have to travel from California through a dozen different autonomous networks (the big blobs that make up the internet "backbone") to my living room in Brooklyn. Instead, it needs to travel only a few miles from a Netflix server that's near, or even inside, Time Warner Cable's local New York City network.

This arrangement violates some definitions of net neutrality. It gives Netflix an advantage — a "fast lane" — over other streaming services that can't afford to pay for CDNs. And by hooking into that local Netflix server instead of reaching all the across the continent, the ISP is arguably discriminating in favor of one streaming service at the expense of others.

But this arrangement also gives me what I want: faster speed without greater cost. Only the most bloody-minded net-neutrality proponents would argue that this is a bad thing. Most people would agree that peering and CDNs benefit the consumer.

MORE: We've Already Squandered Net Neutrality – And That's OK

The mobile model

It's that kind of consumer benefit that the FCC considered a couple of years ago when it chose not to penalize T-Mobile for "zero-rating" certain sources of video content over the company's mobile networks.

Zero rating means that content from some providers — in this case, Netflix, HBO and a dozen other big-name video providers — doesn't count against a mobile customer's monthly data allotment. T-Mobile's plan discriminated against smaller video streamers, yet the FCC let it slide because it benefited consumers, at least in the short term.

As technology-business analyst Ben Thompson pointed out in a recent blog post, this (plus T-Mobile's aggressive pricing) benefited consumers in the long term, too. T-Mobile gained lots of new customers, sparking a price war in the U.S. cellular market that led to plunging subscription costs and more cellular broadband data for consumers.

That's exactly the kind of price war the U.S. home broadband market needs.

"Increasing competition would not only have the same positive outcomes for customers that T-Mobile demonstrated," said Thompson in his blog post, "but would solve the (mostly theoretical) net-neutrality issue at the same time: The greatest check on an ISP is the likelihood of an unsatisfied customer leaving."

Sadly, the competition isn't there yet. While American consumers can choose from among four big nationwide cellular carriers and half a dozen smaller ones, most consumers have only two choices for home broadband: a pricey but fairly fast cable-broadband provider and a cheaper but pitifully slow DSL provider.

Fast fiber-to-the-home broadband, often provided by a telephone company, exists in some places as a third alternative, but its coverage is patchy and is likely to stay that way. My boss can get fiber at his house in New Jersey, but I can't get it in Brooklyn.

A decade ago, Verizon spent millions rolling out its Fios fiber-broadband service to several areas in the Northeast, but in 2010, stopped the expansion in favor of "filling in" territory the company already controlled. Google Fiber reached four cities, then stopped expanding a year ago.

Only AT&T's expansion is continuing, bringing fiber broadband to more locations in California, the South and parts of the Midwest. A University of California, Berkeley, study found that AT&T's fiber coverage was rolling out primarily to wealthy communities.

MORE: Could Net Neutrality Ruin the Internet?

The accidental industry

Cable companies got into the ISP business by a historical accident that shaped the entire broadband industry and led directly to the demand for net neutrality.

In most developed countries, the telephone company's lines are the primary conduit to access the internet. The U.S. started that way too — I remember having the Verizon guy install a second dial-up line in my apartment in 2000 so my wife and I could go online and use the phone at the same time.

"Most consumers have only two choices for home broadband: a pricey but fast cable-broadband provider and a cheaper but slow DSL provider."

But when American consumers started demanding broadband, the phone companies couldn't deliver. Their DSL connections were much slower than the cable companies' connections. (Even today, Verizon can't guarantee me more than 7 Mbps via DSL at my address, less than half what I get with Time Warner Cable.)

The cable companies could deliver fast speeds because they had laid tens of thousands of miles of fat copper wires across the continental U.S. in the '80s and '90s as cable TV went from being a luxury to a near necessity. TV cable wasn't designed to carry two-way traffic, much less internet traffic, but it was quickly adapted to broadband delivery.

Why the cable-TV model is a dead end for broadband

This stopgap, jerry-rigged solution to the demand for widespread broadband access works just fine technically. The problem is that these accidental broadband ISPs still think like cable companies.

Cable companies operate their television-transmission businesses on a local-monopoly basis. They got exclusive television-connection rights to specific towns and neighborhoods in deals made decades ago. There are no such exclusivity rights for broadband, but the costs to build out a competing last-mile broadband network infrastructure are enormous, which is one reason Verizon gave up on its fiber-network expansion.

As a result, the ISP business can be pretty profitable for cable companies.

"It's just very simple economics," Wu told The New York Times in 2014. "The average market has one or two serious internet providers, and they set their prices at monopoly or duopoly pricing."

But once there's no more new territory left to seize, the only way to grow your business if you're a cable-TV operator is to keep raising your rates. Because your customers are captive and can't jump to a different cable-TV provider, you can get away with that every couple of years.

Cable companies pay big cable channels like ESPN and Fox News a few bucks per subscriber per month for the right to carry the channels' signals. But when a cable channel is just starting out, it's the other way around — it pays cable operators for "carriage" of its signals.

So, if cable companies can charge some cable channels for carriage, why can't they charge Facebook or Netflix as well? Why can't they pick and choose which online services their customers can access? The rollback of net-neutrality regulations might make this possible.

This nightmare scenario of internet-content packages — basically, turning the internet into cable TV — is what American broadband consumers are worried about. They don't want cable companies controlling what they can see and do on the internet. That's perfectly reasonable, but net-neutrality regulations may be the wrong solution.

Let loose the lions of competition

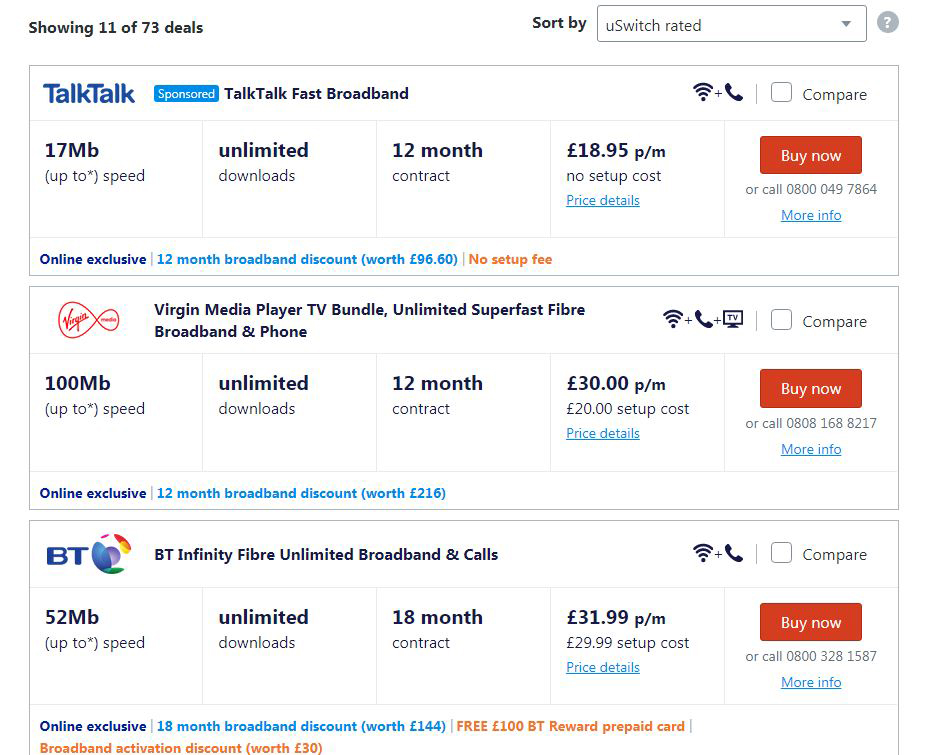

What if you could choose among six or eight different broadband providers and could easily switch from one to the other? That's the situation in many European countries and in South Korea. (For example, here’s what you can get if you live near the American Embassy in London.)

Most of those countries didn't have quite the same level of cable-TV saturation we did, so broadband comes over phone lines as well as cable. Modern phone-line broadband can be very fast; the latest VDSL technologies match or surpass cable-broadband speeds. (The catch is that the VDSL customer often has to be less than a mile from the nearest switching station.)

European and South Korean customers also pay less, often $30or $40 per month, compared to the $60 or $80 many American broadband customers pay. European governments forced the phone and cable companies to unbundle their local loops and open up their broadband lines to competing services, which then scrambled to offer customers the best deals.

But, you may ask, what about that ISP in Portugal that offers different content packages for different kinds of apps, as Rep. Ro Khanna, D-California, tweeted about?

That example is very misleading. The image Khanna forwarded shows the ISP's zero-rated mobile-data add-ons, not home broadband. Choose one of these app bundles, which is an optional supplement to your regular phone service, and those apps' data won't count toward your monthly mobile data usage.

(If you check elsewhere on that ISP's website, you'll see that the company also offers a fiber-based gigabyte-speed home internet, TV and landline-phone bundle for only $70 per month, with no data limits.)

"Wireless broadband will play an ever-larger role in broadband infrastructure." -- Peter Rysavy, president, Rysavy Research

In the U.S., the government forced the telephone companies to unbundle their lines, too — but only for dial-up. Remember EarthLink, MindSpring and NetZero? They were among several dial-up ISPs that used legacy phone-company lines. In a perfect world, every U.S. broadband customer could buy service from them as well as from the cable company.

But in 2002, the FCC decided that broadband was a luxury, not a necessity, and classified it as an optional "information service" rather than as a "communication service" and a public utility. As a result, except in special cases, broadband providers were not obligated to open up their lines to competitors. The providers were only obligated to play by vague net-neutrality-ish rules.

The FCC did belatedly reclassify broadband as a communication service in 2015, but only because Verizon persuaded a judge to nullify the existing weak net-neutrality rules. (That reclassification is what the FCC now plans to reverse.) But the FCC still didn't force broadband providers to open up their lines; it mandated only that they not block any internet content.

Surprisingly, with a few exceptions, net-neutrality advocates have said little about the advantages of opening up broadband to free-market competition. It's the simplest and easiest way to make broadband cheaper and faster for consumers. The ISPs are probably happy that few U.S. customers have considered this issue and instead are worried about net neutrality.

The future may be wireless

So, absent local-loop unbundling, what could give us more broadband choice? Well, just this month, The Wall Street Journal reported that Verizon will roll out wireless home broadband service in a few cities next year.

The service will be based on a "5G" fixed-wireless protocol (I'm using quotations because "5G" hasn't been officially defined) that delivers high-bandwidth broadband at short distances. Customers will have to place routers in windows within the line of sight of the transmitter, which can't be too far away. Prices haven't been announced, but they won't be cheap — at first.

"Wireless is coming up fast as a competitor, especially 5G in a few years that may have effectively greater bandwidth, because it has a vastly cheaper last-mile rollout to the home," Rob Graham, a networking and information-security expert based in Atlanta, told Tom's Guide.

Verizon's not alone. Last year, Google bought Webpass, a company that beams wireless broadband to antennas atop apartment buildings, which then feed via Ethernet to residential units below. This service is already operating in several U.S. cities. And AT&T is testing its own fixed-wireless service.

"Wireless broadband will play an ever-larger role in broadband infrastructure and number of broadband connections," Peter Rysavy, president of Rysavy Research LLC in Oregon, told Tom's Guide. "Challenges are formidable, but none of them are showstoppers, and all [are] resolvable as technology matures over the next several years."

Building out fixed-wireless broadband networks will cost less than laying copper cable or fiber-optic lines. Transmitters can be placed on tall buildings or phone poles, and there won't be a "last mile" to wire to the customer's home.

Two U.S. senators, John Thune, R-South Dakota, and Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, recently drafted legislation that would "fast track" rollout of 5G networks by cutting through local restrictions, in some cases mandating that mandatory local impact reviews regarding deployment of network infrastructure be completed in 90 days.

And don't forget VDSL. It's ideal for cities — the consumer can get very fast broadband over regular telephone lines as long as the company switching station is within half a mile of the customer's home. But like fiber, VDSL is not widely deployed. (This website can tell you what's available in your ZIP code.)

Graham said VDSL is not ideal for many U.S. customers.

"America is more spread out than Europe," he pointed out.

But he said that for the free market to work, "you have to allow some differentiation of product among the broadband providers."

"Net neutrality," Graham added, "strangles any attempt at differentiation."

Rysavy pointed out that broadband from low-Earth-orbit satellites should also help shake up the market. A company called OneWeb plans to offer medium-speed (up to 50 Mbps) satellite broadband to rural areas beginning in 2019, and the private rocket-maker SpaceX plans a similar venture.

"With the rise of 5G, as well as new LEO-satellite broadband services coming online in the next couple of years, broadband competition should increase, which will make the market competitive," Rysavy said.

With luck (and government oversight that encourages new technologies), other companies will jump into the fixed-wireless business, too, breaking the cable monopoly. This will, hopefully, lead to a broadband price war, finally giving U.S. customers the fast, cheap broadband that other rich nations enjoy — and making us forget we ever worried about net neutrality.

Best Security Cameras

The Arlo Q is an excellent security camera with great video quality, strong motion and sound detection and a generous free cloud-storage plan.

The $60 Mini O 1080p is a bargain security camera that provides good-enough video, excellent audio and the essential tools most users need for basic home monitoring.

The Netgear Arlo Pro 2 provides a great combination of software, free cloud storage and video quality.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

-

ithurtswhenipee While I agree we should adopt the European model, to not worry about net neutrality is foolish. Considering that opening up the last mile to competition is the way to go, doing so will require far more laws, regulations, hardware infrastructure, IPS's. This is also not even on the table while repealing net neutrality can and may be done deal with the stroke of a pen. Net neutrality isn't the ideal solution to keeping ISP's at bay, but it is currently the only thing we have.Reply -

iosubx755 The usa will never adopt the European model. Why? because money and greed are very American vs giving people a right to use the internet as a common utility like using water and electricity.Reply -

gpadshore10 There are more insidious and sinister aspects to ending net neutrality which are more long term and very political. Already, Sinclair Broadcasting is busy trying to corner the rural market for talk radio, the best way to control how the "masses" think and vote. Many, if not most ISP markets are single supplier. Get control of these and then make people pay for sites which YOU don't like and they will be silenced only reinforcing your message. This is potentially headed toward an Orwellian "1984" in the 21st century. DO NOT GO GENTLY INTO THAT DARK NIGHT!!Reply -

cyborg_trader This all sounds great, but with our government and business lobbying, the consumer will never win! Several high-speed providers in a town, good luck with that.Reply -

iosubx755 Reply20481206 said:This all sounds great, but with our government and business lobbying, the consumer will never win! Several high-speed providers in a town, good luck with that.

Yep I quit yesterday its for the rich. Screw that shit man, -

DJScribbl It looks like Google Fiber is available in 12 Cities. Not 4, as referenced in the article.Reply

https://fiber.google.com/newcities/ -

iosubx755 Reply20483442 said:It looks like Google Fiber is available in 12 Cities. Not 4, as referenced in the article.

https://fiber.google.com/newcities/

US Constitution 1 and 4. -

jpishgar ReplyThey make tons of money under the existing rules, and they also made plenty of money before the rules were changed.

And they are about to make a whole lot more. One of the arguments made by those hoping to dismantle net neutrality during the proceedings was that none of the ISPs involved in benefiting from this deregulation would dare risk the public relations nightmare that would ensue if they should start introducing fast lanes and segmenting access to sites and services. Well, that's all fine and dandy, but outrage means absolutely nothing in the shadow of oligopoly control.

Where I live, ComCast is the only choice. You can have ComCast, or you can have no internet. This is by design, as ComCast and it's colleague oligopolies have gone to great lengths to produce competition-busting controls over municipal areas by setting up sweetheart deals with municipal governments and negotiating easements with exclusivity. In the event ComCast introduced metered access, requests I pay an additional $19.99 for their "NetFlix XFinity Blast Bundle!", my public outrage would have absolutely no impact on their sales. The very reason that utilities are regulated the way they are is because they are required for survival, and in the overwhelming majority of cases there are no alternatives.

Instead of getting angry about net neutrality, we should be outraged that we Americans pay more for broadband and have slower speeds than consumers in almost every other developed country.

I, unlike ISPs in the near future, have the bandwidth for both. I can be outraged, miffed, ticked, irked, and perturbed by the fact that Americans pay more for broadband access and receive significantly less than in all other developed nations. I can also be incensed that one of the handful of actual functional regulations keeping internet access from becoming as balkanized as cable TV was ended. This isn't an either or. Net neutrality served as a stop-gap to arrest the exacerbation of the other problem of shoddy access at overpriced cost - and now that too is gone.

Only the most bloody-minded net-neutrality proponents would argue that this is a bad thing. Most people would agree that peering and CDNs benefit the consumer.

A substantial number of my tax dollars (and yours) went into creating the technology that ISPs are selling back to me. Are we getting royalties on that, somewhere, that I don't know about? Is there a discount hidden in the myriad charges in my bloated monthly bill? Additionally, a substantial amount of my tax dollars and those of my neighbors goes into maintaining, operating, and keeping safe the land upon which the poles and infrastructure is leased to the ISPs. AT&T, Verizon, and ComCast all pay an effective tax rate considerably lower than what you or I happen to pay (21-32.25% CSIMarket). So while I heartily agree with your assessment that peering and CDNs benefit the consumer, those take place on the service-side, not the ISP side - and they aren't even close to offering a fair trade on this end. Moreover, the deregulation that occurred in rolling back net neutrality did not take place at the local level for states and municipalities, but rather at the national level. This doesn't open up the market to competition - it crushes it.

What economist in their right mind would assert that deregulation of a monopoly or oligopoly encouraged innovation and competition? By reducing the "burdensome regulation on ComCast, it will allow them to __________". I can't really fill in the blank there without laughing. That the most hated company in the entirety of the United States - so much so that it had to rebrand as Xfinity - would voluntarily encourage competition or investment in infrastructure when it just simple does not have to is sparkle pony imagining.

As for the differences between our state of regulation and affordable access to broadband where our European (and other developed nations) counterparts are concerned, there's one massive missing piece of the pie here that isn't taken into consideration. Anti-trust laws are still very much enforced and in effect in those nations. Monopolies and oligopolies are not tolerated, particularly with matters of goods and services of necessity. The EU literally has "National Competition Authorities" to ensure that competition is neither distorted nor restricted. I'd be super in favor of rolling back net neutrality and intensely deregulating internet access markets... provided AT&T, Verizon, ComCast, and Time Warner all get shattered into a hundred pieces. AT&T should be familiar with the process, having been blown up before back in the days of "Ma Bell". Deregulate to your heart's content! As a consumer, I'd like to pick and choose from 12 ISPs who compete with each other, rather than just the one.

Kudos for making the case that perhaps the destruction of net neutrality isn't the internet apocalypse, but it's a straw too many and a bridge too far for most consumers. The internet is a need today, not a want, and with the elimination of net neutrality we are more and more at the mercy of less than a handful of ISPs acting in concerted effort to divvy up access and squeeze every last dime from their option-devoid market.

I will be consistently bothering my local representatives, municipal, state, and federal, to return net neutrality in the form of strong legislation. And, I'll also mention that perhaps now is the time to rev up the ol' antitrust chaingun and take a good long look at non-competitive practices of some of these ISPs.

-JP