What is the Syrian Electronic Army?

They took down the New York Times' website and caused the stock market to plummet. But what do we really know about the SEA?

The Syrian Electronic Army has been in the news a lot lately — in more ways than one. But who are they, what is their motivation, and why have they had so much success thus far?

They've taken down The New York Times, hijacked the Associated Press' Twitter feed and duped many into believing the White House had been bombed (the world panicked and the stock market plummeted before the deception was discovered).

This group of hackers, which supports the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, also appears to be responsible for hacking a number of other media websites, including NPR, The Washington Post and fake news site The Onion. In early August, the SEA hacked the blog of a contributor to Britain's Channel 4 news and posted a fake report of a nuclear strike on Syria.

MORE: 13 Security and Privacy Tips for the Truly Paranoid

In each case, the hacks seemed to come in response to an article or post that the SEA deemed anti-Assad.

The SEA's favored hacking methods include distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, in which hackers bombard a website with so many page views that they overwhelm the servers, effectively taking the website offline.

The SEA is also known to use phishing, which means sending official-seeming emails and websites to trick people into divulging login information. Once the SEA has this information, it places false or inflammatory posts on the compromised accounts.

Neither of these techniques is particularly sophisticated in terms of technical skill, but the SEA has been able to use them to great effect.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

The most high-profile attack came on Aug. 27, when the SEA (or an organization claiming to be the SEA) effectively knocked The New York Times' website offline.

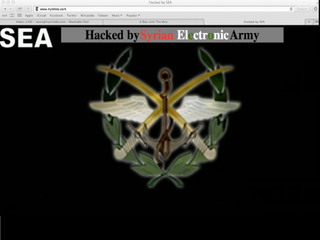

This time the SEA used a domain name system (DNS) attack, which is when attackers cause a url (in this case "www.nytimes.com") to be associated with a different webpage. In this case, visitors to "www.nytimes.com" instead found themselves on a website emblazoned with the banner "hacked by Syrian Electronic Army."

In terms of technical savvy, a DNS attack is only slightly more sophisticated than the SEA's previous attacks. However, given the prestige of its target and the amount of control — however brief — the SEA gained over The New York Times' Web domain, it appears the SEA is upping the ante of its attacks.

Who are the Syrian Hackers?

Knowing what the SEA has done and how they did it is one thing. But it's still unclear exactly who and what this group is.

"The SEA is not an organization that we understand," Kevin O'Brien, an enterprise solutions architect from cloud security company Cloudlock, told Tom's Guide.

"There's not a group of actual state hackers — [the SEA] seems to be a quasi-political group of hackers who are doing certain things in the name of a political conflict happening around the world," he wrote.

The SEA first appeared in May 2011 when its first website, Syrian-es.com, went live.

At first, this website described the SEA as a group of young Syrians with no official ties to the Syrian government who wished to "fight back" against the country's enemies. However, two weeks after the website went live, the part claiming that the group was unofficial was removed.

The SEA's ties to al-Assad

Most of the SEA's websites were registered by the Syrian Computer Society, which serves as a registry for Syrian-based websites. The Syrian Computer Society was founded by Bashar al-Assad's brother Bassel al-Assad in 1989, and Bashar al-Assad later headed it before becoming president.

The Syrian Computer Society even gave the SEA a domain name ending in ".sy" (as opposed to ".com" or ".org"), which is usually reserved for official Syrian Computer Society websites. This is the SEA's only confirmed government connection.

In a June 2011 speech, Bashar al-Assad praised a number of Syrian citizen groups for supporting his regime, including the SEA, which he said "has been a real army in virtual reality."

The SEA posted on its website that it was honored to be acknowledged, but reiterated that it had no official ties to al-Assad's government.

MORE: 5 Free PC Security Programs Worth Downloading

In 2013, a representative of the SEA describing himself as "a (not the) leader" told The Daily Dot that "we are not supported by anyone or part of the government. We are just Syrian youths who want to defend their country against the media campaign that is full of lies and fabricated news reports."

In April 2013, a U.S. Web service provider called Web.com seized hundreds of domain names registered in Syria, citing trade sanctions against Syria as the reason for the action. Due to this action a majority of the SEA's websites offline, so the SEA moved the domains "sea.sy" and "syrianelectronicarmy.com" to a Russian Web host.

All that this background tells us is that some type of group calling itself the "Syrian Electronic Army" exists. The SEA's membership, recruitment methods and internal hierarchy are still a mystery.

Without more information about how the group makes decisions and executes attacks, it's impossible to know whether the SEA is responsible for The New York Times attack or even any of the other attacks associated with the group.

For example, just because the SEA claims responsibility for a hack doesn't necessarily mean that it's responsible; the group may be trying to increase its fame by riding on others' coattails.

Similarly, there's no way to tell whether a hacker claiming to represent the SEA actually has any ties with the organization.

And it's unclear what kind of resources or training the SEA has. They may not work directly with the Syrian government, but experts suspect that the SEA's membership includes some current and former government officials.

Thus far, the SEA has only launched unsophisticated attacks, but what the group lacks in technical finesse, they've made up for in persistence. As shown by the string of high-profile disruptions they've caused, their methods are working.

Email jscharr@techmedianetwork.com or follow her @JillScharr. Follow us @TomsGuide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Jill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.

-

expl0itfinder This is the future of warfare. And it will have a much more devastating effect than any bomb or chemical ever could.Reply -

Jack Revenant expl0itfinder, while I certainly agree that internet warfare is the future, it's madness to say that it will (or can) have an impact "more devastating than any bomb or chemical". At the end of the day, this is information warfare, which can certainly have devastating impacts, but nothing near the sheer damage in loss of lives that high-yield bombs and chemical weapons (to say nothing of nuclear weapons) can inflict.Reply -

axehead15 You'd think more advanced IT security personnel work at the NY Times... Shouldn't they be able to stop this from happening?Reply -

agnickolov @axehead15: Unfortunately this post didn't provide much in terms of details, but the reality is that the attack did not take place within the NY Times -- it was carried out on their domain registrar located in Austria. Apparently they used phishing and obtained the credentials of the master admin account at the domain registrar. The original article I read on Yahoo mentioned also that the same registrar is responsible for some really high profile domains like microsoft.com, so SEA had the potential to do some serious damage for the hour to hour and a half they had their access within the registrar.Reply -

ethanolson "We are just Syrian youths who want to defend their country against the media campaign that is full of lies and fabricated news reports."Reply

So they just hack news sites and post fabricated stories themselves. Sounds very youth-ish to me. -

gm0n3y I wonder if Russia has been giving them any help? They certainly have the motive and the means.Reply -

LatanyaRPowell what Amy explained I'm shocked that some people able to profit $5047 in 1 month on the internet. discover here www.wℴrk25.ℂℴmReply