Could 'Watch Dogs' City Hacking Really Happen?

The hackers in the video game 'Watch Dogs' hack ATMs, streetlights and more with ease. Is that really possible? We asked the experts.

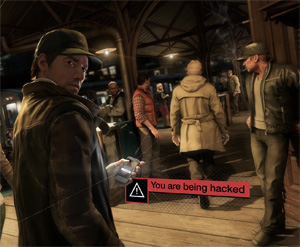

In the video game "Watch Dogs," player-character Aiden Pearce hacks a city's streetlights, drawbridges, ATMs and more — just by tapping on his smartphone.

The near-future version of Chicago in which the game takes place is tied together by a citywide operating system called ctOS, which connects everything from traffic lights and ATMs to cars and cellphones — and also collects reams of personal data on each citizen into allegedly private profiles.

Manipulating the city through ctOS forms the core of the player's actions in the game, as well as the story. But how realistic is a citywide operating system, and what are the advantages and disadvantages of such hyperconnectivity? We asked the experts.

The genesis of 'Watch Dogs'

The idea of manipulating a connected city came from conversations in the offices of game developer Ubisoft Montreal.

"We were talking about the impact of social media on society, and at the same time, we were talking about this every day around beers and coffee — we were stuck in the building at Ubisoft Montreal filled with geeks who love technology," Jonathan Morin, the game's creative director, told Tom's Guide. "So we started to think about that, and how an urban environment would extrapolate because of those technologies."

Those conversations led to ctOS, but Ubisoft also wanted to make sure its depictions of hacking in "Watch Dogs" were as accurate as possible.

In early 2013, Ubisoft Montreal reached out to Kaspersky Lab, a well-known, Moscow-based antivirus firm. Kaspersky researchers had just uncovered the massive cyberespionage campaign Red October, in which a real-life group had used sophisticated malware to infect computers and gather information on government, research and military targets around the world.

The Red October malware, like the Flame malware discovered a couple of years earlier, could collect surveillance data from a number of different sources, similar to how Pearce controls many different parts of the city from his phone.

MORE: Most-Anticipated Games of 2014

Red October and Flame could turn on a computer's microphone to record audio, and could hack webcam streams to get visual data on its targets. Red October could also collect data from smartphones and enterprise network equipment such as email and FTP servers.

When Kaspersky consultants joined the "Watch Dogs" project, Ubisoft Montreal had already worked out the game's plot, including the idea for ctOS, according to Kaspersky.

"They wanted to take a progressive approach in the gaming industry, when it comes to cybersecurity, by making their new game as authentic as possible," said Vitaly Kamluk, a Kaspersky researcher who worked with Ubisoft. "We were able to provide technical consultation and recommendations for the theoretical cyberscenarios in the game, both during in-game play and in character/plot developments."

Real-life vs. near-future hacking

That's not to say that everything Aiden, the protagonist of "Watch Dogs," does is currently possible — at least not in the way he goes about doing it. Everything hinges on ctOS.

"Something like [ctOS] does exist already, but it's not a large single system, [but] rather a number of smaller systems, working independently," Kamluk told Tom's Guide.

Ironically, it's ctOS' very comprehensiveness that makes it so susceptible to attack.

"I think the conceit that this future city has everything connected to a network is important," said Alex McGeorge, head of Washington, D.C., operations for Florida-based software security company Immunity Inc.

"[ctOS] would imply that connecting to the city's wireless [network] would provide you with a path, however convoluted, to the bridge controls, and so forth," said McGeorge, who advises companies on how to protect themselves from security threats. "If that were true today, then you could do this from a cellphone, today.

"In principle, what he [Aiden Pearce] is doing with infrastructure is entirely possible," McGeorge added. "It's just not so streamlined as to fit inside a smartphone-sized device quite yet.”

Without a centralized, all-encompassing network like ctOS, Aiden would need a lot of additional gear to hack into all the systems he accesses during the game.

For example, this May, Cesar Cerrudo, chief technology officer for Seattle-based security company IOActive Labs, demonstrated at the INFILTRATE hacking convention that he could intercept the signals transmitted by in-road traffic sensors to feed false data to the traffic-control systems of major cities in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Australia and China.

But Cerrudo's hardware was backpack-size, not smartphone-size, like Aiden's in "Watch Dogs." McGeorge said Aiden would need more than one backpack.

"I would imagine you would need a similar setup [to Cerrudo's] for each thing you're trying to hack, especially if it runs on a dedicated radio spectrum," McGeorge said. "If someone were to put forth some engineering time towards solving the power and size demands, then sure, within a few years, you could have a pocket-sized device that does that."

Why would any city implement something like ctOS?

Given the apparent ease with which Aiden hacks into ctOS to steal money, cars and information, who would ever implement a connected city like the Chicago of "Watch Dogs"?

Kevin O'Brien of Waltham, Mass.-based cloud security company CloudLock doubts that anyone would create something like ctOS.

"Doing so would create a single point of failure for some pretty critical systems, and nobody would really do it in practice," O'Brien said.

Instead, most security experts prefer to construct compartmentalized networks in which various parts of a system are kept separate. If one part is compromised, the other parts are theoretically still secure.

"Generally speaking, both network architects and organizations are allergic to the idea of a single source for all system data," O'Brien said. "This is why, for example, companies adopting cloud technologies tend towards hybrid models rather than a single vendor."

However, Kamluk argues that systems like ctOS have certain advantages.

"To reduce costs and increase efficiency, it makes sense to make it a single central, citywide system in the future in the U.S. and in other countries," Kamluk said. "Centralized approach is more convenient to use, makes it easier to maintain, and after all, it reduces the attack surface."

Furthermore, he noted, "ctOS has a kind of intrusion alert system, which can detect an attack and locate an attacker."

However, "if the system is compromised, then the attacker may get enormous power, as you see in the game," Kamluk added. "[ctOS] is vulnerable and centralized. It allows an intruder to do too much: to stop trains, to initiate blackouts, to control city traffic-light systems … To be as secure as possible, a ctOS should at least consist of multiple systems separated from each other."

But compartmentalization is not always easy to achieve.

"It's hard to design and maintain, and it's expensive — usually more expensive than anyone wants," said Dave Aitel, founder and CEO of Immunity. "So the world [of "Watch Dogs"] is believable.”

That hacking feeling

ctOS aside, the experts we consulted said that the hacking depicted in "Watch Dogs" is a far cry from the experience of today's hackers.

"Hacking generally takes a long time, requires whiteboards and other nonexciting paraphernalia, and 15 years of highly specialized knowledge not generally found in people who are also great at shooting guns and doing parkour," Aitel said.

"This is generally why hacking in the movies tends to be someone in the sidelines who has a weight problem and glasses, and not the main hero," Aitel said. "It's not that you can't be a fit hacker — and I do know a few into parkour — but usually, you spend your time sitting around reading things on a computer in a nice comfy chair."

That's not to say the "Watch Dogs" team didn't try.

"We were digging for a contemporary world," Morin told us. "A lot of people look at 'Watch Dogs' as a near-future type of experience, which is fine and understandable, but from our standpoint, we're simply creating an alternate version of Chicago in the contemporary world."

The "Watch Dogs" team also tried to make sure Aiden and the other hackers in the game were using the correct terminology.

"We went to [hacking and security conference] DEFCON, we used those guys to make sure the language we used was respectful of the underground of hacking, that the kind of words would be right," Morin said. "We also inspired the kind of graphical visual from [hacking], so it's very old-school graphics."

That "pop-cultural visual" is not quite the reality, however. "None of it is quite as sexy as hitting a button on a smartphone," O'Brien told us. "Most 'real' hacking also lacks a [graphical user interface]."

Yet "Watch Dogs" may be on to something. Though Aiden's neat and tidy graphical user interface comes from the fact that everything he wants to do exists on the single, cohesive network of ctOS, in real life, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is working on something called Plan X, a video-game-like visual interface designed to give government hackers that same cohesive experience while defending and attacking multiple networks.

DARPA's Plan X depicts network connections as shimmering spider-web-like threads, similar to what you see in "Watch Dogs." It even has Oculus Rift virtual-reality support, whereas "Watch Dogs" does not.

So even without ctOS, individuals may some day have the same range of possibilities all in one interface.

"Watch Dogs" may have taken some liberties, and done some extrapolating beyond current technological capabilities. But the hyperhackable world it depicts is not all that far-fetched. Even if Aiden's world isn't the reality of today, it's very possible that something like it is just around the corner.

Email jscharr@tomsguide.com or follow her @JillScharr and Google+. Follow us@TomsGuide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Jill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.

-

jakjawagon ReplyCerrudo's hardware was backpack-size, not smartphone-size, like Aiden's in "Watch Dogs." McGeorge said Aiden would need more than one backpack.

You could always use a smartphone to remotely control larger hardware located elsewhere. -

neon neophyte most of our infrastructure is online and sadly, easily hackable. watchdogs isnt too far off base.Reply -

MalcolmTucker It will be interesting when Apple centralizes power related to in-car entertainment, home and car security. It will become a large target; likely a bigger target than Microsoft ever was.Reply

Microsoft platforms are used to collect and manage data. But if Apple starts creating platforms and devices to manage physical things, It's not difficult to imagine it will attract much more attention of hackers because of the typical, and wealthier demographics of the usual Apple customer. -

gsfsdfsdfdf ReplyIt will be interesting when Apple centralizes power related to in-car entertainment, home and car security. It will become a large target; likely a bigger target than Microsoft ever was.

power is already centralized in SCADA

Microsoft platforms are used to collect and manage data. But if Apple starts creating platforms and devices to manage physical things, It's not difficult to imagine it will attract much more attention of hackers because of the typical, and wealthier demographics of the usual Apple customer.