WannaCry Ransomware Attack: What You Need to Know

Here's what we know, and what we don't yet know, about the ongoing WannaCry ransomware attack.

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

UPDATED 4:54 p.m. EDT Monday, May 15, to add possible North Korean connection, as well as other updates.

UPDATED 3:00 p.m. EDT Friday, May 19, to add that WannaCry fails to spread to machines running Windows XP.

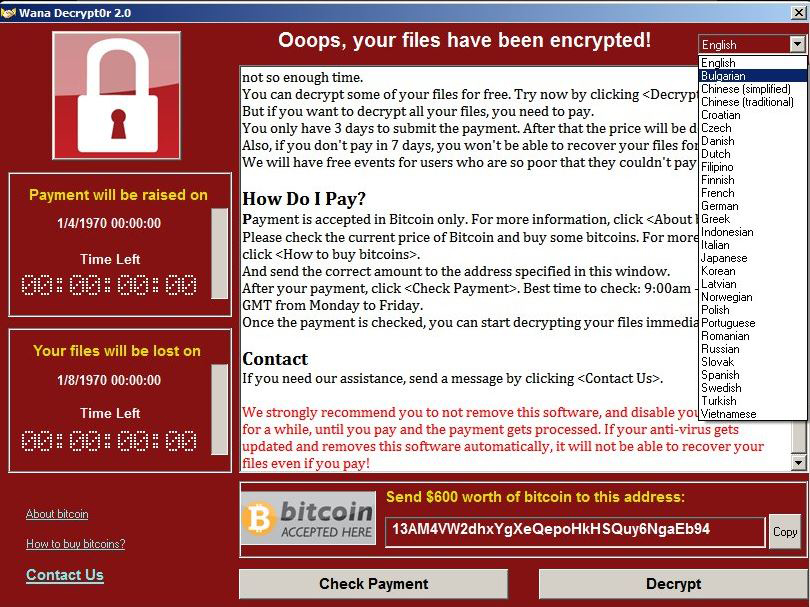

Encrypting ransomware is far from new, but that didn't stop a strain dubbed WannaCry (also called WanaCryptor 2.0, WCry, WanaCrypt or WCrypt) from locking down systems around the globe on Friday (May 12). So how did this attack manage to cripple so many systems, and is it coming back?

Article continues below

What does WannaCry do?

The ransomware encrypts most of the user files on a Windows PC with virtually unbreakable encryption. A message is posted on the computer's screen informing the user that he must pay a ransom — usually about $300 — in the online cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Two countdown clocks on the screen tell the user how much time remains before the ransom is doubled (usually 3 days), and how much time remains before the encrypted files are deleted altogether (usually a week).

However, Windows PCs running Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows 8.1 and Windows 10 that have installed Microsoft's system updates since March should be immune to WannaCry infection, at least for now. Late Friday, Microsoft took the extraordinary step of releasing patches against WannaCry for Windows XP and Windows 8, neither of which are still supported.

[UPDATE Friday, May 19: It turns out that the original version of WannaCry has trouble remotely infecting at least the 32-bit version of Windows XP. Windows Vista and later remain vulnerable if left unpatched, and newer versions of WannaCry might be able to fix the problem and infect XP.

"The worm that spreads WannaCry does not work for XP," Jerome Segura, lead malware intelligence analyst for Malwarebytes, told Tom's Guide Friday. "You'd have to install the ransomware by other means, which is why there aren't many infections on XP at all."]

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

WannaCry does not infect computers running macOS/Mac OS X or Linux. However, it can infect computers that are running Windows in emulation software or virtual machines, and Macs that can boot into Windows.

MORE: Best Antivirus - Top Software for PC, Mac and Android

Where did WannaCry come from?

We don't yet know. This is actually the second variant of the WannaCry malware. The first appeared a few months ago and spread via phishing emails, which require the recipient of the email to open an attachment before the malware can try to infect a computer.

This new version spreads much faster. It incorporates ETERNALBLUE, a software exploit (a method of punching through a piece of software's security) that was developed years ago by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). In April, a group called the ShadowBrokers posted the source code for ETERNALBLUE and several other NSA tools online for anyone to see and use.

On Friday, a hacktivist group called SpamTech claimed responsibility for the attack, but without offering proof. For now, that claim is not being taken seriously.

UPDATE: Slight but significant clues have established a possible North Korean link to WannaCry.

Google researcher Neel Mehta cryptically tweeted out two file signatures Monday. One was for WannaCry; the other was for Contopee, malware used in an an attack in February 2016 on the central bank of Bangladesh that netted $81 million for the attackers.

Matthieu Suiche, a French security researcher based in Dubai, followed Mehta's lead and quickly showed striking similarities between Contopee and an early variant of WannaCry, found in February 2017, that did not use the ETERNALBLUE exploit. Russian antivirus firm Kaspersky Lab also noted the similarities.

Crucially, Contopee has been tied to the Lazarus Group, the attackers who nearly destroyed the computer systems of Sony Pictures Entertainment in the September 2014. And most security researchers, as well as the U.S. government, have blamed North Korea for that attack.

Kaspersky admits that the similarities may be part of a "false flag" attack aimed at pinning blame on North Korea. Claudio Guarnieri, an Italian security researcher based in Berlin, admits that there are similarities between the two strains of malware, but also that "this type of code is widely available and the basis might be reused or acquired."

How does WannaCry work?

Once inside a business or organization's network, WannaCry uses the ETERNALBLUE exploit to leverage a flaw in Microsoft's Server Message Block (SMB) protocol. It will spread to any connected Windows PC that has not been updated to guard against ETERNALBLUE. Once it lands on a vulnerable system, it encrypts office, image, movie, database and email files, and demands a ransom of at least $300.

How did WannaCry spread?

We don't yet know how it travels from the internet to computer systems or networks. Unlike a lot of the malware that spreads today, WannaCry doesn't appear to rely on the social engineering tricks seen in phishing emails as ransomware usually does.

Instead, it appears to move from system to system on its own. The rapid spread of the malware Friday, and the lack so far of any samples of phishing emails specific to this attack, indicate that WannaCry may be a computer worm, spreading throughout the world without human assistance.

Can WannaCry be stopped?

Amazingly, the initial WannaCry outbreak ended by accident on Friday. While he analyzed the ransomware's code, a 22-year-old information-security professional in England who goes by the pseudonym MalwareTech noticed a web address in the code.

Following standard procedure, he investigated the address and discovered that no one had registered it. Once he set up a server at that address, he noticed that the WannaCry samples he and other researchers were analyzing suddenly stopped infecting machines. It turns out that the domain name functioned as a kill-switch, which may have been designed to stop detection of WannaCry by researchers using "sandboxed" virtual machines.

Is WannaCry coming back?

It almost certainly will. Several new variants and copycats have already been spotted. One used a different web address as a kill switch, and was quickly shut down; another had no kill switch, but had a faulty payload that failed to encrypt any files. But other variants will not repeat those mistakes.

Is WannaCry going to attack my computer?

It certainly will try. We've yet to see accounts of WannaCry hitting home Windows machines, and the lack of such reports indicates that the malware may have an easier time infecting workplace computer networks that are more likely than home machines to have the Microsoft SMB file-sharing protocol open to the internet. But that doesn't mean home machines aren't being infected, and it would be easy for cybercriminals to repurpose the ransomware so that it attacked machines via phishing emails or corrupted websites.

What can you do to prevent infection by WannaCry?

The most important thing you can do is install the system updates marked as important in Windows Update. To do so, open the start menu, type "windows update" into the text prompt, and select Windows Update from the results. Then, follow the on-screen instructions to install updates.

As mentioned above, Microsoft has also released patches for Windows XP and Windows 8, but it's possible that Windows Update on those machines may not have access to the patches. If so, you can download the patches manually using the links at the bottom of this Microsoft security advisory.

Be sure to choose the link for your specific version of Windows XP or Windows 8, noting especially whether you have the x86 (32-bit) or x64 (64-bit) versions of the OS. If you're not sure, open the start menu, click Control Panel, change View to Small Icons and then click System. A page should appear displaying information about your computer and its operating system.

What can I do if I'm infected by WannaCry?

Unfortunately, there's not a lot you can do. Your files will have been strongly encrypted, and you won't be able to crack the code. Bleeping Computer points out that you just might be able to recover some lost files by using the free ShadowExplorer utility, which will locate your computer's automatic file backups.

Symantec says that the ransomware deletes most of the user's files after it encrypts copies of them, which means that some files might be recoverable using a common undelete tool. But the Symantec blog posting also notes that original files on the user's Desktop or My Documents folders, as well as on any removable drives, would be fully overwritten instead of deleted, and hence unrecoverable.

As for paying the ransom, that might not work. The ransomware appears to have been hastily put together, and doesn't appear to have any kind of method by which a victim's ransom payment will automatically unlock the victim's files. Instead, it seems the criminals behind this will have to manually unlock the victim's files, but doing so would likely reveal their locations to authorities around the world.

"Paying the ransom does not guarantee the encrypted files will be released," the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Computer Emergency Readiness Team said in an advisory Friday. "It only guarantees that the malicious actors receive the victim’s money, and in some cases, their banking information. In addition, decrypting files does not mean the malware infection itself has been removed."

Matthew Hickey, a British software researcher who uncovered WannaCrypt's clunky payment system, told Wired that the ransomware's authors may not even be out to make money.

"I absolutely believe this was sent by someone trying to cause as much destruction as possible," Hickey told Wired.

Henry was a managing editor at Tom’s Guide covering streaming media, laptops and all things Apple, reviewing devices and services for the past seven years. Prior to joining Tom's Guide, he reviewed software and hardware for TechRadar Pro, and interviewed artists for Patek Philippe International Magazine. He's also covered the wild world of professional wrestling for Cageside Seats, interviewing athletes and other industry veterans.

-

Paul_324 Always make daily offline backups to drives that you physically unplug immediately after backing up. Then, if you wake up one morning/come home from work one day and you notice your computer is infected, wipe the drive, reinstall windows, and restore your backed up files.Reply

Club Benefits

Club Benefits