Why Apple Should Rethink the iPhone's Name and Its Entire Product Line

Experts agree that Apple has a problem: its product line is getting too complicated and its brands are getting confusing. It's time to follow Jobs' prime directive and get back to basics.

What's Apple going to call the next iPhone? iPhone XI or iPhone 11? What about the R variant? Will the next be named XIR, 11R or XRS? Perhaps it's time for Apple to rethink its iPhone naming.

And its entire product line, too, because it's all quickly turning into a cluster-you-know-what.

Apple's main competitor has been thinking about renaming its flagship phones for a while. In 2018, Samsung Mobile CEO DJ Koh said that the company will stick to Galaxy, but it was thinking of dropping the S and numbering system after the 10. Rumors of the company rebranding its 2020 phones resurfaced again last month.

But Apple's problem is not only naming its future phones. It's about the iPhone line itself and the rest of the Apple products.

Right now, someone working at the Apple Store can't honestly help the average Joe when asked if it is better to buy the iPhone XR or the XS. "Well, the XR has a bigger screen, which is better, but the XS smaller screen has a higher quality, although it can burn," John Appleseed will tell a buyer, "but both products run at the same speed and have more or less the same specs — except the XS has two cameras instead of one camera. AND both have Animoji…." It doesn't sound like a clear explanation in any way. There's not a clear distinction and a clear message.

The same applies to other Apple products. For example: laypeople — not tech heads — get easily confused by the MacBook and the MacBook Air. The "Air" had a meaning back when all the other MacBooks were heavier — but now the former is clearly lighter than the latter. So what the hell does Air mean for me?

The truth is that Apple's product line is a mess. And thus consumers are getting confused.

Simplification was the key to Apple's success

There was a time when Apple's product line was a lot easier to understand.

“Historically, Apple has founded its business in simplicity,” said branding expert Joseph Anthony, CEO of the Hero Group Inc. "Now, they are hurting themselves with so many product variants."

For Anthony, at some point you have to ask yourself if there is a way to simplify this instead of making so many different SKUs. (SKUs are stock keeping units, a technical way to refer to each distinct product you can order from a company.)

MORE: Best Smartphones - Here Are the 10 Best Phones Available

This will be a hard exercise. The Cupertino, California, company is facing extreme pressure from two sides. First, Asian manufacturers are releasing myriad models at different price points — phones and electronics that match Apple's quality and, in some case, surpass them in functionality.

Second, consumers are no longer keen to pay Apple's premium prices for upgraded products that have dubious positive impact on their lives. With phones and electronics turned into commodities with little distinctions between each other, Tim Cook and his minions are struggling to keep people from escaping their ecosystem by introducing new (slightly) cheaper products for those who can't afford the top of the line.

This is not a new situation for Apple. Back in the '90s, facing extreme competition from Microsoft and the PC clones, Apple fell into the same trap of trying to have multiple products to cater to consumers and professionals. In a few years, the company's product line had grown to dozens of product lines and hundreds of SKUs.

"Apple has founded its business in simplicity. It was always the benchmark, but now they are hurting themselves with so many product variants." —Joseph Anthony, CEO, Hero Group Inc.

When Steve Jobs came back to Apple in 1997, there was the PowerBook, the Power Macintosh, the Macintosh Performa, the Macintosh LC, the Network Servers, the Workgroup Servers, the Newton, the Newton MessagePad, the eMate, the StyleWriter, the LaserWriter, the Multiple Scan Displays, the ColorSync Displays lines. And all of those had multiple numbers attached to them, things like 3400, 5500, 7300, 8600 or 9600. And that's only from memory — I'm sure I'm missing more stuff.

MORE: Galaxy S10 Plus vs. iPhone XS Max: Which $1,000 Phone Wins?

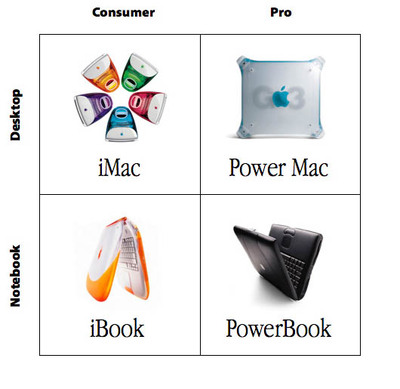

Obviously, buyers were confused. And Apple's development, manufacturing and product stocking was a total mess. So, the first thing Jobs did when he replaced Gil Amelio as interim CEO was to call each product manager and axe — well, almost everything. He brutally simplified the product line and rebranded half of it, creating his famous 2 x 2 Apple product quadrant.

Apple products were divided in two: Consumer and Pro. And those were going to be divided in desktop and notebook. That's it. The iMac and the PowerMac, the iBook and the PowerBook. All of a sudden, consumers had a clear idea of what to buy. Sure, these products have different specs. You could buy a Power Mac in good, better and best configurations, each with different processor speeds and different RAM and storage options. But you knew what you were getting from the beginning: a computer for professionals. Same with the other products.

"General best practices for naming are to think many generations ahead and ensure extensibility for an evergreen system," Jake Hancock, a partner of brand strategy at global branding company Lippincott, told us over email. Jobs' quadrant system guaranteed that.

But as the company became bigger and more successful, complexity started to build up in the product line. The iPod came — with variants like nano, mini and shuffle. The iPhone, of course, went from simply iPhone to iPhone 3G and 3GS, the 3G meaning a communication standard and the S the revision to the original 3G. After the 4, the numbering sequence started, adding the S suffix every other year. And there was the iPad, with the Mini, the Air and the Pro.

Bionic, Retina, Liquid Display, Neural Engine, QuantumAudio, TrueDepth. One of those is fake, but 99 percent of people don't know that — or what the hell these things mean.

Things got a lot more complex, but at least there was some logic to it all. The MacBook Air, for example, had a clear branding.

But eventually the company fell victim to its own innovation, as Anthony told me. The prefixes and suffixes that were supposed to add context instead became confusing. "When you see Pro you instantly think it is for professionals," Anthony said. "But R or S doesn't really mean anything [...] adding a letter is not enough to inform the consumer."

That is true. If you are layperson, this doesn't add any context. You need to educate yourself before making a decision, and that's not good.

Even worse: in this competitive market, Apple is overemphasizing features by giving them new brand names, like Bionic, Retina, Liquid Display, Neural Engine, QuantumAudio, TrueDepth… One of those is fake (QuantumAudio), but 99 percent of people won't know that — or what the hell the other things mean for that matter. And that's a problem.

The solution is complex

"Parallel conventions across product families offer another way to simplify the [buyer's journey]," Hancock points out. "A Pro and Air version of iPhones may not be right, but in a perfect world, the brand could create one disciplined approach across all products."

But we don't live in a perfect world and there is not a simple solution for all this. It is a problem that affects both the (excess of) product SKUs and a promotional issue, with names that lead to confusion.

Obviously, Apple needs to keep competing with Android manufacturers regarding phones, so it needs products to address other segments if it wants to keep people buying hardware, and its ecosystem thriving. The App Store and its subscription services have became the growth engine for the company, and you need lots of people using your hardware to keep that engine going.

"A Pro and Air version of iPhones may not be right, but in a perfect world, the brand could create one disciplined approach across all products." —Jake Hancock, partner of brand strategy, Lippincott

So how do you solve this product mess? According to Hero Group's CEO, at some point you have to ask yourself if there is a way to simplify the product line like Jobs did.

But, in addition to that, you need a better branding strategy. Apple has been the gold standard of what branding should be, Anthony said. It needs to create a master brand that it can continue to invest in over time, adding meaningful sub-brands that give consumers a clear idea of what these products to do for them, to quickly understand their attributes.

One obvious solution for the iPhone is to drop the numbering and the S convention and just use iPhone or iPhone X. "Like the automotive industry, just use the release year to identify them," Anthony tells me. People already know that, if they are buying the 2019 model, that's going to be "the best phone that Apple has ever built." It is obvious.

MORE: Apple's Big 'Show Time' Event March 25: Three Things to Expect

Hancock points out that there "will be greater emphasis on the model names (S versus R) and less on the generation names, which have less relevance to customers who either want newest/best or most affordable — or special features like size or color — and have little personal investment in version 10 or version 11."

But the S and the R don't tell much, like we already discovered. You need sub-brands that instantly tell regular consumers what they are buying without being part of the fanboy club. "iPhone X versus iPhone X Pro or whatever you want to call it," Anthony said, "but you need to create a language that gives a more distinct idea of what it is, which will result on a more efficient business model."

"The key for Apple will be learning how much complexity their customers are willing to learn and remember," Hancock told me. “My guess is they are nearing the limit with multiple coexisting generations and versions of alphanumeric names."

I believe that we are way past that limit already. Apple needs to come up with a new Jobsian product matrix. Not a 2 x 2, obviously, but one that allows them to keep growing, building their brands and expanding their products without being confusing for consumers. That much is clear.

Credit: Tom's Guide

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Jesus Diaz founded the new Sploid for Gawker Media after seven years working at Gizmodo, where he helmed the lost-in-a-bar iPhone 4 story and wrote old angry man rants, among other things. He's a creative director, screenwriter, and producer at The Magic Sauce, and currently writes for Fast Company and Tom's Guide.