Why the iPhone 5S Will Kill Your Point-and-Shoot Camera

Point-and-shoot cameras can go home now. The new upgrades in the iPhone 5S camera make it clear that smartphones will be taking the place of traditional cameras.

You may not care about the fingerprint reader or space-gray color option for the new iPhone 5S. But its camera could really change how you use your phone — and make you stop using a point-and-shoot camera.

Not only iPhones, but also many Android and even Windows models have pushed the limits of what a smartphone camera can do, making the inclination to lug a point-and-shoot camera ever smaller. Apple seems to have nudged smartphone photography further along with the iPhone 5S camera, which promises better low-light photos and high-speed photography to compete with the more-sophisticated point-and-shoots. It also blows past "real" cameras with a new flash technology that should provide better color than any traditional cameras can.

MORE: Top 7 Features of Apple’s iPhone 5s

"The value proposition for a compact camera or a camcorder has decreased once again," Chris Chute, director for imaging research at analyst firm IDC, told Tom's Guide. "It's just another example of adding features that could only be found on standalone [cameras] to the mobile platform."

Why big pixels matter

It's curious that Apple started down in the weeds by talking about the phone's new image sensor and larger pixels. But the sensor is where the iPhone's transformation into camera killer began.

The first three iPhone models (original, 3G and 3GS) had abysmal cameras that, ironically, may have jump-started the photo-app craze. Apps like Hipstamatic and later Instagram applied various arty effects to iPhone photos, at first mostly to hide how crappy the unadorned pictures looked.

In 2010, Apple got serious about photos, introducing a sensor in the iPhone 4 with a just-emerging technology called (unfortunately) backside illumination. This tech moves a lot of the wiring to the back of the sensor where it won't block light from reaching the pixels in the front. (That sounds like common sense, but wasn't easy to do.)

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Apple didn’t invent the tech, but the company put it to good use. All things being equal, more light = better photos, especially in dark places like the pubs and music halls where those Hipstamatic hipsters hang out.

Apple has pushed the photographic upgrade farther with the 5S. According to its presentation, the new iPhone gets an additional 15 percent of imaging area from the same-sized chip and uses that gain to make bigger pixels, not more of them. Apple even called out the size of each pixel: 1.5 microns across. (A micron is one-thousandth of a millimeter, or about 0.000039 inch.)

MORE: Smartphone Camera Shootout 2013

"That's important in going beyond the megapixel discussions," Ben Arnold, director of industry analysis for consumer technology at research firm NPD, told Tom's Guide. He also credited Apple with giving just enough jargon to make a point, without overwhelming people.

That measure, known as pixel pitch, really is significant, as it allows Apple to meet and even exceed the quality of point-and-shoot cameras. Canon's well-regarded PowerShot point-and-shoots, for example, have pixel pitches ranging from 1.3 to 1.9 microns. Its Elph 330 HS (priced at $180) has a pixel pitch of 1.54 microns. (Of course, other factors, such as the lens and image processor, play an important role in image quality; and it's too early to know how the whole camera system of the iPhone 5S will compare.)

"If Apple takes the camera feature seriously, they're on the right track with the larger pixels. … That's clearly a benefit on the new models," said Chute.

The iPhone 5S camera is still no match for an SLR, however. For example, Canon's $900 (with lens) Rebel T5i has a pixels pitch of 4.3 microns, resulting in pixels that that are more than eight times the size of the new iPhone's.

High-speed photography

More tangible than the new sensor geometry is what it (and the processor) can do, including shooting 10 photos per second. The iPhone analyzes this burst of images and picks the best one to use as the final photograph. Sony pioneered similar technology several years ago in its Cybershot point-and-shoot cameras and then expanded out to higher-end models, such as its NEX Mirrorless cameras. That was a killer feature that point-and-shoots had over smartphone cameras. Not anymore.

The new iPhone camera can also capture video faster, at up to 120 frames per second. Play that back at the standard 30 fps for video, and you have 4X slo-mo. Just imagine the "Oh no!" videos of cats slowly heading into collisions with household objects that will flood Instagram and Vine.

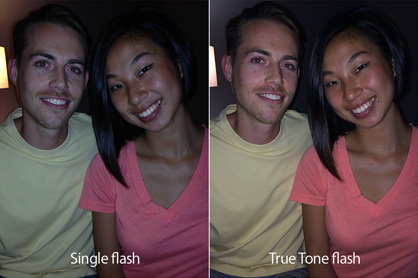

Color-balanced flash

The most impressive feature, though, is what Apple calls a True Tone Flash. Typical camera flash has the slight bluish color of daylight. That's great for brightening up shadows in a sunny-day photo. But it's a buzz killer at night. That lovely orangey color of a sunset, candlelight or even an incandescent light bulb is blown away in a blitz of blue.

By mixing the light from two LEDs — one white and one amber — the iPhone 5S promises to match the lighting in any environment, complementing rather than contrasting with it. It's an advance remarkable both for how much it can improve photos and for how long it took someone to utilize long-existing technology to make that improvement.

Smartphone cameras may not have technically surpassed the quality of the better point-and-shoots. But they are getting so close that even more people may decide it's time to leave that other camera at home.

Follow Sean Captain @seancaptain. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Sean Captain is a freelance technology and science writer, editor and photographer. At Tom's Guide, he has reviewed cameras, including most of Sony's Alpha A6000-series mirrorless cameras, as well as other photography-related content. He has also written for Fast Company, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Wired.

-

house70 "It's curious that Apple started down in the weeds by talking about the phone's new image sensor and larger pixels. But the sensor is where the iPhone's transformation into camera killer began."Reply

Obviously the 'Captain' here never heard of HTC One.

Only thing missing here is the signature "typed from my precious iDevice". Really uninformed fanboi article. -

kyzarvs Have they managed to fit a good optical zoom lens into an iPhone?Reply

No? Not sure how it's going to make a real camera redundant then... -

Onus Absurd on its face, when you consider the price, AND that further expenses will be ongoing, due to data plan rates.Reply

-

glasssplinter Like kyzarvs said, is there an optical zoom? Then they will never replace a REAL camera. Don't get me wrong, the ability to quickly snap a picture and email it is very convenient but anything that I actually care about quality I'm using a REAL camera. Oh and I can change the batteries in my REAL camera if they run out. Can the icrap do that? Phone camera does not equal REAL camera quality.Reply -

wopr11 "Did the Lumia series not try to make this clear? Wow such apple bias. "Reply

Easy to tell when a "journalist" writes something that apple tells them to write - and how to write it. -

gagaga 90% of what is on Tom's appears 2 days after other sites, and now they are printing apple-supplied advertorials as articles.Reply -

jldevoy Most reviewers seem to fawn over anything Apple does, the Lumia line have been pushing better cameras for a year and all reviewers could say was there's no instagram etc...i'm not sure I would buy the best camera phone on the market then turn all my photos into grainy shitty instagram snaps that all look the same.Reply -

razor512 A good lens is one of the most important important parts of a camera as it works with the larger pixels to provide them with enough light. A tiny lens significantly lowers your low light performance. A canon 5D with a high end L lens offers better image quality than a canon 1dx with a cheap lens. The iphone 5 camera heavily relies on software lens correction to deal with the extreme barrel distortion in addition to distortion around the center of the image due to the shape and flawed design of the lens. You can see this for your self by taking a picture of some sand or anything finely textured then look at the changes in sharpness and how certain non sharp details are actually stretched due to the lens correction. From the looks of it, the 5s may still have that issue.Reply