Google's New Titan Key Looks Super Secure - There’s Just One Problem

Google's upcoming Titan Key is a physical device that may be able to render 2FA security nearly impregnable.

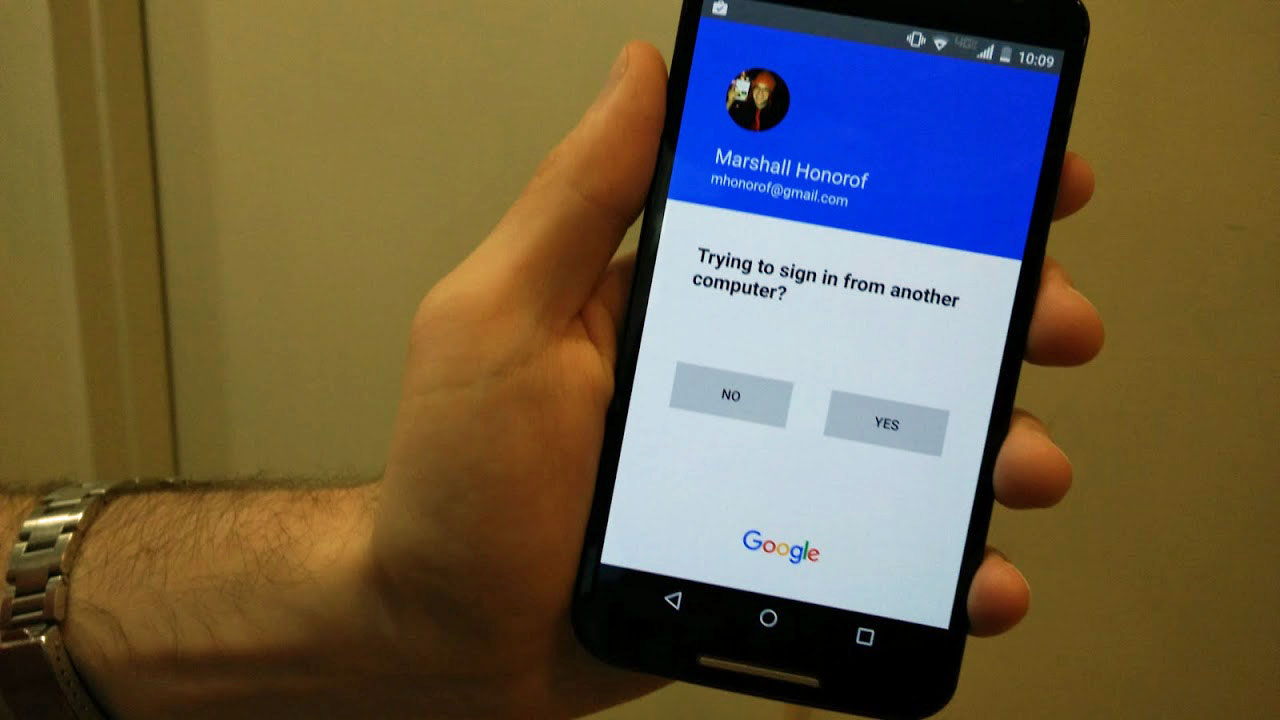

Activating two-factor authentication (2FA) on your e-mail, social media and financial accounts is a fantastic idea. By tying logins to one of your personal devices, you can foil most cybercriminals who want to compromise your identity. "Most," however, does not equal "all," and that distinction can be vital if you're a politician, business leader, reporter — or Google employee.

Google's upcoming Titan Key is a physical device that may be able to render 2FA security nearly impregnable. The trouble will be getting people to use one.

Keys to success

CNET tried out the Titan Key in an extended hands-on, and if you're familiar with physical security keys, you're probably already familiar with the basic concept. Like Yubikey and similar devices (which Google already supports), the Titan Key is a physical USB or Bluetooth dongle. After logging into a Google account with your username and password, you have to either plug in the USB key or connect to the Bluetooth dongle. This is generally much more secure than a phone-based 2FA code, since there's no way for a malefactor to intercept a physical key short of theft.

MORE: How to Enable 2FA

The devices will cost about $50 together, or about $20 to $25 individually. They'll be out within the next few months, but Google has not nailed down a price or release date yet.

Other than that, the keys really seem to be as straightforward as Google describes them. The Titan Key has only one purpose: providing ironclad 2FA security without relying on a phone or tablet. After all, phones often have trouble receiving text messages in foreign countries, maintaining a battery charge for more than a day — or staying completely safe from cybercriminals.

On Twitter, security researcher Shane Huntley pointed out that 2FA codes sent to phones are eminently phishable, and he is by no means the only one. In his example, an attacker sets up a fake-but-convincing website, then directs a user to it. The user inputs his or her username and password. In response, the attacker attempts to log in to the real website, which sends an SMS code to the original user. The user inputs his or her code into the fake site, and that's the end of that. The attacker has now fully compromised an important account with some rudimentary HTML and careful timing.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Adoption challenges

Savvy users, of course, realize that the situation described above is extremely inefficient, and would not work as a large-scale phishing attack. However, Google isn't concerned about phone-based 2FA letting down everyday users; it's worried about savvy hackers trying to spear-phish politicians and other high-profile targets.

By using methods just like the one described, Google's internal security team was able to fool Google employees into giving up their credentials and 2FA codes. If Google employees can fall for a sufficiently sophisticated attack, what chance does the average congressman have?

However, convincing people to carry around yet another gadget constantly will most likely be an uphill struggle. Even now, Google can barely convince any of its users to use code-based 2FA. If fewer than 10 percent of Google account holders want to activate free 2FA on devices they already own, the chances of them purchasing $25 dongles are not promising. That's especially true when you consider that, without a dongle, you may not be able to access your account at all.

Imagine forgetting to stash your key in your backpack before you head into the office — or worse, before you leave for a week on a business trip. Like standard 2FA, there are backup protocols, but that's yet another layer of setup between the end-user and his or her data.

Still, if Google can't convince everyone to use the Titan Key, perhaps it can at least convince the right people to use it. If the Facebook hearings are anything to go by, the American government generally has a poor understanding of how the Internet works, as well as the reasonable precautions that it can take to keep its employees safe online.

Given the choice between carrying around a USB dongle and leaking vital American secrets to a spear-phisher at a server farm somewhere in Eastern Europe, many high-profile individuals will probably go for the former.

Marshall Honorof is a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.