FBI Head: Apple, Google Encryption Leads to 'Dark Place'

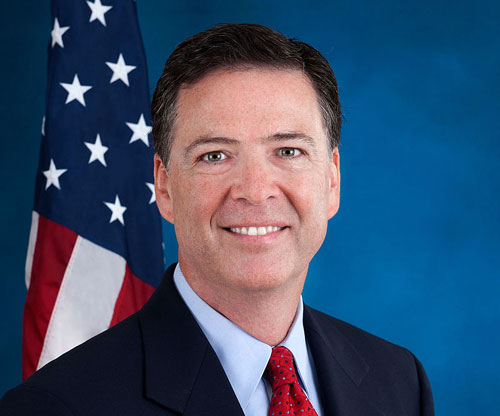

FBI Director James Comey told a Washington audience that the privacy features of Android and iOS devices would let criminals go free.

FBI Director James Comey gave a strong speech today (Oct. 16) explaining why law enforcement should have access to data on encrypted smartphones. But he failed to cite any examples in which such law-enforcement access could have made the difference between life and death.

"Technology has become the tool of choice for some very dangerous people," Comey told the audience at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., in a speech entitled "Going Dark: Are Technology, Privacy, and Public Safety on a Collision Course?"

"Those charged with protecting our people aren't always able to access the evidence we need to prosecute crime and prevent terrorism," Comey said. "We have the legal authority to intercept and access communications and information pursuant to court order, but we often lack the technical ability to do so."

MORE: How to Encrypt Your Files and Folders

For those reasons, Comey explained, the FBI is seriously concerned about the encryption features in Apple's and Google's latest mobile operating systems, both of which would render data on a phone inaccessible to anyone but the phone's authorized user. In law-enforcement slang, the data would "go dark."

"The information stored on many iPhones and other Apple devices will be encrypted by default," Comey said. "Google announced plans to follow suit with its Android operating system. This means the companies themselves won't be able to unlock phones, laptops and tablets to reveal photos, documents, e-mail and recordings stored within."

"Both companies are run by good people, responding to what they perceive is a market demand," he said. "But the place they are leading us is one we shouldn’t go to without careful thought and debate.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

"If the challenges of real-time interception threaten to leave us in the dark," Comey said, "encryption threatens to lead all of us to a very dark place."

The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994 mandates that telecommunications companies must give police the ability to listen in on telephone conversations. CALEA covers landlines and cellular carriers, and was expanded in 2004 to cover Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) providers and broadband Internet service providers.

For the past few years, the FBI has sought another expansion of CALEA, this time to gain access to encrypted Internet-based communications such as instant messaging and social networking. The White House has refused to act on the FBI's requests.

"If a suspected criminal is in his car, and he switches from cellular coverage to Wi-Fi, we may be out of luck," Comey said in his speech. "If he switches from one app to another, or from cellular voice service to a voice or messaging app, we may lose him."

"There will come a day — and it comes every day in this business," Comey said, "where it will matter a great deal to innocent people that we in law enforcement can't access certain types of data or information, even with legal authorization."

Imperfect examples

Comey made a distinction between monitoring "data in motion," which he defined as "real-time court-ordered interception of phone calls, e-mail and text messages and chat sessions," and examining "data at rest," or "court-ordered access to data stored on our devices, such as e-mail, text messages, photos and videos."

Accessing data in motion involves intercepting communications as they are made, similar to a wiretap, and would be clearly covered by an expansion of CALEA. Accessing data at rest involves examining archives of communications that have already taken place; such examinations are covered by search warrants and require no legal expansion.

Comey made clear that losing access to communications archived on cellphones was a primary concern. He cited four cases in which examination of data stored on cellphones was instrumental in winning convictions. Yet each example was far from ideal.

One case concerned the murder of a 12-year-old Louisiana boy, in which evidence on both the victim's and perpetrator's phones helped convict the killer. Comey didn't explain how decryption could have prevented the murder.

In another, GPS location data on a suspect's smartphone tied him to a fatal hit-and-run accident in Sacramento — but Comey didn't mention that cellular-tower triangulation and tower logs could have also put the suspect in the right time and place.

The two other cases involved archived text messages, which are not retained by cellular carriers for long, if at all. (The FBI has pushed for legislation that would compel carriers to retain text messages for two years.)

One involved a Los Angeles toddler beaten to death by her mother; text-message archives established that both parents knew of the crime and tried to cover it up. The other involved a Kansas City heroin ring whose organization was revealed from archived text messages on searched phones.

Comey did not say, however, that cellphone data had cracked cold cases or led to new suspects — it simply added to evidence against existing suspects.

Comey cited a fifth case, this one in Kansas, where a deleted cellphone video helped exonerate several men facing rape charges. He didn't make clear whether the phone in question belonged to one of the suspects -- who would have reason to unlock encrypted devices that could prove their innocence — or to someone else who might have been implicated instead.

In a question-and-answer session following his speech, Comey was asked if he could cite a specific case in which someone would not have been rescued as a result of cellphone encryption. He could not.

"It's time that the post-Snowden pendulum be seen as having swung too far in one direction," Comey said. "Have we become so suspicious of government, and of law enforcement, that we will let bad guys walk away?"

- 12 Mobile Privacy and Security Apps

- Can You Hide Anything from the NSA?

- 12 Computer-Security Mistakes You're Probably Making

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and gaming. Follow him at @snd_wagenseil. Follow Tom's Guide at @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

-

junkeymonkey that's right your privacy needs to be illegal and you should put all of you out there for them to keep tabs on you at all times as they see fit .. I mean who the hell do you think you are keeping you life privet?? shame on youReply

all I read in civics class about America and communism I now wonder if they got that wrong ??

the commies said '' we will change and take over America with out firing a shot'' looks like there close to doing that .. ever notice how after 911 how your rights have quickly dwindled away in the name of freedom and home land security ??? like just to get a job or driver license you now have to clear and be reported to the gov for there ok to be hired ?? ya in order to punish the threats to us we got to punish ourselves first look at pictures of commi states police ,Russia china so on from 20 years ago to today they look like military forces now look at you police force in town its not the cops in the nice blue uniform that shows up it the military bdu dressed guy with a m16

democracy and communist is now a gray area and a thin line between them

folks say well we got the Constitution and bill of rights , well them s just a piece of paper and is only as strong as YOU to back it up not your elected officials -

hajila ReplyAnd BTW, even if you get a warrant I will never ever hand over my password for my encryption. My personal stuff is mine and will always remain mine!

That's okay Hardy because they don't need your password. They have the ciphers to open up anything they please. Just stay on the right side of the law or stay small enough to go unnoticed and you'll be fine. Otherwise, I'm sad to say, they can get anything they please.

-

cats_Paw "One case concerned the murder of a 12-year-old Louisiana boy, in which evidence on both the victim's and perpetrator's phones helped convict the killer. Comey didn't explain how decryption could have prevented the murder."Reply

If you need to access the phone of someone dumb enough to keep incriminating evidence on his phone in order to get a conviction, perhaps you need to hire smarter people.

oh wait... smarter people dont like the FBI.

-

Skylyne Reply

It really depends on which encryption method is used, as the alphabet agencies have most encryption methods cracked. There are still some methods of encryption that are up in the air, concerning whether the NSA has cracked it, but it doesn't mean they definitely have. By default it's best to assume they have it cracked, but the likelihood of them using such a cipher is quite low; you'd have to really pose a substantial threat to national security, as decrypting someone's phone with a cipher is a pretty big deal. While it's possible they could plug it into a laptop and rip everything off in ten minutes, that forces them to admit there is no safe encryption; and admitting that would then cause every known intelligence agency to focus even harder on cracking encryption further... and that creates a giant shit storm of cyber insanity. It's within the interest of national security to keep what little encryption secrets we have left quiet.14392395 said:That's okay Hardy because they don't need your password. They have the ciphers to open up anything they please. Just stay on the right side of the law or stay small enough to go unnoticed and you'll be fine. Otherwise, I'm sad to say, they can get anything they please.

In fact, I'm sure Snowden has something leading to the NSA's potential capabilities of AES cracking. If he does, I would assume he didn't leak them for a similar reason. Admitting he even has such a thing would cause some serious problems in the security and hacking community alone, and agencies like NSA and GCHQ would have a field day over this information (both literally and sarcastically). It would be a very tough thing for everyone to swallow, if all encryption was cracked by now. While agencies could take advantage of that, it then creates more problems than it solves.

There's a much bigger picture they are trying to keep on the DL than many want to believe; and it's all for good reason. I may not support it, but it is fairly logical in their position.. -

junkeymonkey likw osoma Obama care -- government strong arming at its bestReply

''oh wait... smarter people dont like the FBI.''---

no that's wrong , its the fbi don't like smart people out smarting them

-

HEXiT i love how there claiming this is to stop crime.Reply

when all the evidence was gathered after a crime happend.

it hasnt stopped anything, just helped secure a conviction after the fact.

which they probably had enough evidence for anyway without going through the user data.

i mean come on the terrorists (the reason these powers were given) are in the middle east. thats where they need to be gathering data, both from the web and on the ground. not sitting at home like a barnacle sticking your feelers out and grabbing what ever passes your terminals to the interweb

technology cant keep us safe and any 1 that thinks it can is mistaken. it can help you prove your case after the fact but theres little to no chance of catching something before it happens... case in point the Boston bombings. the guys had phones, they communicated about what they were doing for months before hand but was there any 1 there to stop them on the day? NO!. the government were clueless (or so they claim)

-

Marcus Marik The government can crack any *individual* encrypted system by throwing enough computing power at them. What they can't do is crack *all* of them. They're whining and moaning because encryption forces them to limit themselves to a small set of genuine suspects (i.e. what they're supposed to do anyway) rather than spying on everybody.Reply

-

everygamer Encryption is a double-edged sword, we protect personal information, but the bad people of the world have ways to communicate and plan in secret. It's always finding that balance between personal security and national security that makes sense.Reply

At the end of the day, if Apple and Goole encrypt the data, the FBI, CIA and NSA can still access that data by supenaing Google and Apple to provide the data. This is the balance, we protect our private data, and the government has to go through proper legal process to obtain personal data. Seems the fair way to do it. -

jakjawagon Replythe place they are leading us is one we shouldn’t go to without careful thought and debate.

Like all the careful thought and debate that nobody (at least publicly) had before the NSA and GCHQ started intercepting internet traffic. -

The Shootist The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.Reply

INCLUDES DIGITAL DEVICES