The Hack Volkswagen Didn't Want Car Thieves to See

A research paper Volkswagen had suppressed for two years described how to crack the code an ignition key sends to an ignition switch.

If you own a Honda, Volkwagen, Volvo, Porsche or certain model of Cadillac, Chevrolet, Pontiac or Buick, you better watch out — thieves could steal your car by hacking the encrypted radio signal emitted by the ignition key.

That's the upshot of a research paper presented last week at the Usenix security conference in Washington, D.C., after having been suppressed by court order for two years. It details three different attacks against the wireless chips meant to prevent car thieves from cloning car keys.

The good news is that to pull this off, a thief would need access to both the legitimate key and the car it fits. The bad news is that a valet-parking attendant or an unscrupulous mechanic could do it. The worse news is that there's no easy way to fix this problem.

MORE: Volvo XC90 Test Drive: Look Ma, No Hands!

A lot of recent car-hacking research has explored interfering with the car's operation while in motion, or getting the doors to wirelessly unlock. But it's rare to find a hack that lets you start the car and then drive away.

The paper, entitled "Dismantling Megamos Crypto: Wirelessly Lockpicking a Vehicle Immobilizer," and authored by Baris Ege and Roel Verdult of Radboud University in the Netherlands and Flavio Garcia of the University of Birmingham in England, was originally meant to be presented two years ago.

But Volkswagen got an English court to apply a gag order, which was lifted only recently after the researchers redacted a single sentence.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

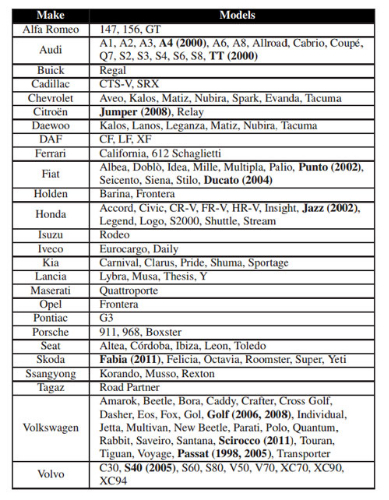

In their paper, Ege, Garcia and Verdult listed 26 vulnerable makes, among them Volkswagen, including Audi, Porsche, SEAT and Skoda models; Fiat, including Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Lancia and Maserati models; and Honda. Thirteen individual vehicles were directly studied, including a Volkswagen Golf, an Audi TT, a Volvo S40 and a Honda Fit (known as a Honda Jazz in Europe). Volkswagen told Bloomberg News that its current models were not affected.

Also listed were several General Motors models, most made overseas. They included cars made by Daewoo of South Korea, including the Chevrolet Aveo and the Pontiac G3, and the late-model Buick Regal, which is made by Opel in Germany.

The only North American-built models on the list were the Cadillac CTS-V and SRX. But because the researchers focused on cars sold in Europe, there may be other GM models as yet unlisted. No GM Models were directly tested.

All three attacks detailed in the paper involve recording the short-range radio signals sent between the transponder on a car's ignition key and a car's ignition switch, and require radio-frequency-analyzing hardware and a key programmer that together retail for about $650.

But only one attack requires a specialized encryption-cracking computer to crack all codes; decryption in the other two attacks can be performed on an ordinary laptop in time spans ranging from a few minutes to half an hour.

Automotive key exchange

A transponder is a radio coil built into modern car keys. When the key is inserted into a car's ignition switch, the switch sends a powerful radio signal to the key, which gives the key enough power to respond with a secret code. The car's computer compares that code with its own code to verify that the key is meant for that particular car.

Without a correct exchange of codes between transponder and ignition, the car won't start, even if the ignition is hot-wired. The entire system is called an "immobilizer." Immobilizer codes are meant to be impossible to crack, and immobilizer ignition keys impossible to duplicate outside of a dealership.

Since immobilizers became commonplace on new vehicles in the late 1990s, car theft has plummeted, especially in North America. The system works so well that many new cars don't need, or even have, ignition keys; instead, the driver presses a key button on a wireless keyfob that contains the transponder, then presses a Start button on the dashboard.

The lack of a physical key removes one authentication factor. But until this paper was released last week, that wasn't a problem.

Gone in 30 minutes

This long-suppressed paper threatens to end the security guaranteed by immobilizers. It may even help explain why car theft has lately been on the uptick in Europe, especially of luxury makes.

The trio focused on transponders that used the Megamos Crypto encryption algorithm, developed by Thales of France. (Thales joined Volkswagen in applying for the English injunction.)

The researchers found that the Megamos Crypto algorithm had a fundamental problem: It doesn't generate random numbers properly, giving a code-cracker an edge. The algorithm could be cracked to reveal the code in about two days using a specialized code-cracking supercomputer — probably not within the budget or area of expertise of most car thieves, but certainly achievable by a well-funded government agency.

Even then, the algorithm was not implemented correctly on all makes. On some models (the researchers wouldn't say which ones), the key transponder's memory was not locked; the key programming tool could write to the memory, forcing the transponder to reveal the secret code in about half an hour.

On other models, the codes were much shorter than they were supposed to be. Even without writing to transponder memory, a laptop could use a pre-computed "rainbow table" to get the code in a few minutes. (The one-time construction of the rainbow table, applicable to all immobilizers with short codes, would take about 5 days on a code-cracking supercomputer.)

Your bank card is safer than your car key

There isn't a lot that the average car owner can do to fix this. Ege, Garcia and Verdult advise that in the case of an unlocked key-transponder memory, the owner can lock the memory using specialized tools. But few will try something that's hard to do, may brick the immobilizer system and may not work anyway.

The researchers could only state that "it is important for the automotive industry to migrate from weak proprietary ciphers" such as Megamos Crypto to better-understood algorithms such as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). They also suggested that car makers pony up a bit more cash and start using slightly more expensive transponders that use better pseudo-random-number generators, such as those use in cellphone SIM cards or chip-and-PIN bank cards.

"For a few years already, there are contactless smart cards on the market which implement AES and have a fairly good pseudo-random number generator," the researchers write. "It is surprising that the automotive industry is reluctant to migrate to such transponders, considering the cost difference of a better chip (≤ $1 USD) in relation to the prices of high-end car models (≥ $50,000 USD)."

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.