Apple Isn't Being Honest About Terrorist's iPhone

Apple says it's been ordered to 'backdoor' the San Bernardino shooter's iPhone. That's not quite true, and it's important to understand why.

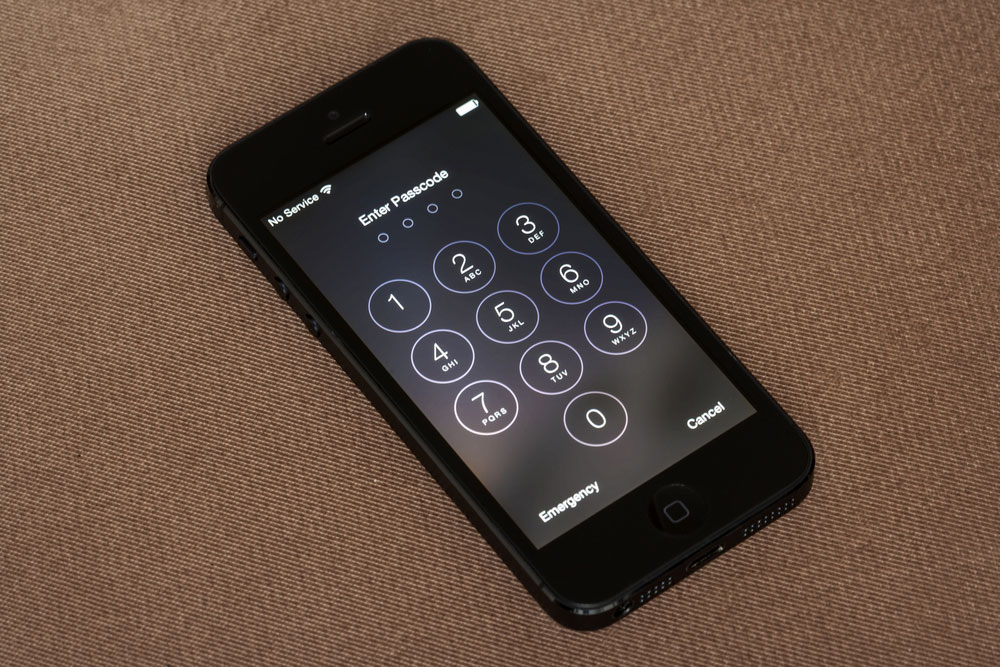

A federal judge yesterday (Feb. 16) ordered Apple to comply with an FBI request regarding the decryption of an iPhone 5c used by Syed Rizwan Farook, who, along with his wife, killed 14 people in the San Bernardino massacre in December.

Apple CEO Tim Cook refused, writing in an open letter on Apple's website that "the U.S. government has asked us for something we simply do not have, and something we consider too dangerous to create. They have asked us to build a backdoor to the iPhone."

But Cook is being disingenuous. Apple is not being asked to hand over a backdoor or a master key. It's not being asked to decrypt Farook's iPhone. Rather, Apple is being asked to let FBI technicians decrypt the phone themselves. That's very different.

Judge Sheri Pym wrote in her court order that "Apple shall assist in enabling the search of a cellular telephone [specified as Farook's device] .... by providing reasonable technical assistance to assist law enforcement agents in obtaining access to the the data on the subject device."

Specifically, Pym ordered Apple to disable two security features on Farook's iPhone: first, the rate limiter which incrementally slows down the rate at which you can input successive incorrect PINs; and second, the self-destruct trigger which erases the content of the iPhone after 10 incorrect PIN entries.

RELATED: iPhone Back Door Will Save Lives

Once those features are disabled, the FBI might be able to brute-force Farook's PIN without risk of erasing all the data on it. That "might" depends on what kind of PIN Farook used to lock the phone's screen, because the PIN encrypts and decrypts the phone's contents.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

If Farook used a four-digit PIN, then the PIN will be "cracked" in less than an hour. A six-digit PIN will probably take several hours. But if Farook used a long, complex alphanumeric passphrase, it could take months or years. (The phone was Farook's work phone, and belonged to the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health.)

But disabling the rate limiter and the self-destruct trigger is not the same as giving the FBI a backdoor into Apple's encryption protocols. It's not even giving the FBI special tools to crack into the phone -- the FBI already has those tools. Rather, it's just stepping out of the way to let the FBI do its job.

There are a couple of ways in which Apple could disable those features. A technician could install an Apple-signed firmware update from a computer, preferably Farook's own. Or, less likely, Apple could push out an over-the-air update specifically targeting Farook's phone. In either case, the change would apply only to Farook's device, and not anyone else's.

Tim Cook was right when he argued in Apple's statement yesterday that "this software — which does not exist today — would have the potential to unlock any iPhone in someone’s physical possession."

But the FBI isn't about to release this code into the wild, and Apple could design the update so that it works only on Farook's phone.

Apple opposes this request because it sets a dangerous precedent. If Apple complies, other law-enforcement agencies around the world will be able to cite this as proof that Apple will cave to demands to decrypt a phone.

"Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices," Cook argued. "In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks."

From a legal and political standpoint, Apple's argument is completely legitimate. Every law-enforcement and intelligence agency worldwide wants a backdoor into Apple products. And by refusing to comply with the order, Apple is trying to force a higher court to decide the constitutional merits of the case, and possibly take it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

But technically speaking, disabling the anti-brute-force features isn't the same as creating a backdoor. And in any case, disabling those features may not even be possible on newer iPhones.

As security experts Robert Graham, Dan Guido and Jonathan Zdziarski pointed out in separate blog posts, the iPhone 5s and later models store the PIN and handle the encryption using a Secure Enclave, which is impossible to alter with a firmware update without erasing the device's contents. If so, then the FBI is lucky that Farook used an iPhone 5c. (A former Apple employee, John Kelley, argued on Twitter that the Secure Enclave could indeed be altered safely.)

Unlocking Farook's iPhone won't bring back the victims of the San Bernardino massacre. The data on the phone may help prevent further attacks, but will more likely be used to locate possible accomplices and build cases against them.

And the authorities aren't being completely honest, either, when they say such requests are a matter of national security. The case of Farook's iPhone may not be. The NSA would be brought in if a real serious, imminent threat were involved. Judging from recent statements by the NSA's current and former directors, both of whom went against the FBI and supported Apple's encryption efforts, the NSA probably doesn't need Apple's help to break into an iPhone.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

-

Lee_Saenz I'll get in the iPhone for a fee. I know the information wouldn't be admissible in court, but at least they'll have the knowledge to see whats in the terrorist's iPhone. I would charge the FBI and want my criminal record completely wiped clean, and then we have a deal. I wont give you my name, but you are the FBI and can contact me in person if you want. The fee would be a little steep, tax free 300K... and the clean record, which is free for you. I would do it at home, in my own PC... I want immunity while I work, and don't need lessons on the laws I will break for national security. I don't want a job either, just this once I'll help you out... and no recognition please... I want to remain anonymous, or NO DEAL!!Reply -

Alexander_K "But technically speaking, disabling the anti-brute-force features isn't the same as creating a backdoor. And in any case, disabling those features may not even be possible on newer iPhones."Reply

That's plain wrong. Apple needs to create a specific Firmware version in order to "stepping out of the way to let the FBI do its job", and they need to hand it over to them. First, this is exactly what we call a "backdoor". Second: what prevents the FBI from ripping this Firmware off of the phone, disassembling it and then using it on other cases, where they *don't* have a warrant?

"But the FBI isn't about to release this code into the wild" maybe not into the wild, but they will probably release it to other agencies.

No offense to your patriotism, but we know since Snowden that US Government agencies are not always benevolent and that they are often very willing to use every means possible to infringe on peoples privacy.

We don't need Apple handing them the tools to do so. -

brucek2 Apple's language, designed for a layman, may be a little imprecise. But it paints exactly the right picture. By allowing the FBI to remove the anti-hacking measures, they make the phone easily crackable. And in legal terms, once they've done it once, and it is a matter of record that this build of the software exists, than it can be easily and repeatedly asked for.Reply

Today it's to "combat terrorism" (although these particular terrorists are already dead, and any information on the phone is weeks old); tomorrow it could be because you might have ordered soda in too large of a serving size. And that's just for the US. The second Apple agrees to do this for the US, every other government will demand the same tools, some which won't even pretend to have any valid reason.

I look forward to a day when our government can demonstrate that it will use extraordinary tools for extraordinary purposes only. Until then, the only safe policy is to not allow the tools to exist in the first place. -

Dave_47 Paul, you are disregarding the main issue. Sure Apple can unlock this particular phone with modest effort. The greater issue is whether Apple can legally continue to manufacture devices containing strong encryption and no government backdoor. That is the issue Apple is fighting, and for the sake of all of us, I hope they win at the Supreme Court.Reply -

cvxxxv There is no legal reason to need the information that may be in the phone. But there is compelling security reaons to secure the contents. Soon pay by phone will be a norm in the US as it is and has been in many other countries. The public has more to fear form criminals than from terrorists.Reply -

Jasey_ I am sorry about the people that died in San Bernadino, there is a country of 323 million people sacrificing security of 94 million people with iphones will not stop terrorism, it will just make it worse because as soon as anyone finds out that it's hacked then they will use other means. If you want to stop terrorism then the US has to stop terrorizing middle east countries abroad.Reply -

sporkster My heart goes out to the victims of the San Bernardino massacre. But this is really dangerous for Apple to unlock the Farook's phone at the request of the law enforcement because in the future, this will set the precendent for future requests from law enforcement to break into any iphone. Hope Apple takes this all the way to Supreme Court and they win.Reply -

cvxxxv I'm with you on this!!! If people know what the laws contained they would be terrified. Laws still on the books from ancient times and precedents that made sense in 1800 but not today.Reply