Apple Patents Glass MacBook Keyboard That Bends Under Your Fingers

A new patent shows that Apple is working on a glass touch keyboard for MacBooks that would go way beyond haptic feedback.

A new patent by Apple shows how it may solve its MacBook keyboard woes in future iterations of the laptops.

Published Jan 31 by the USPTO (and spotted by Digital Trends), the patent seeks to bridge the gap between the physical keyboards still used on laptops and desktop computers, and the touchscreen keyboards we are all used to seeing on smartphones.

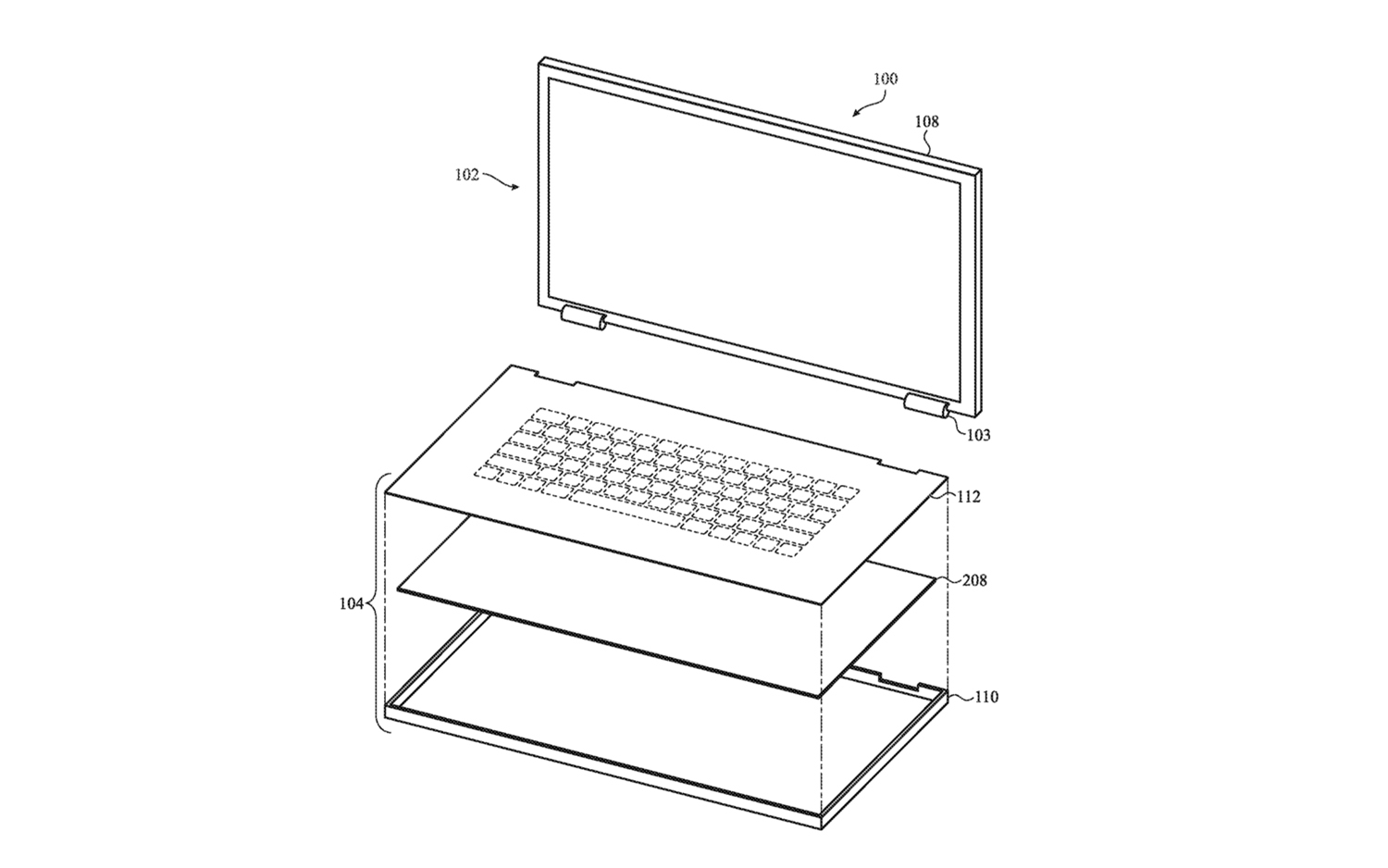

The display of the laptop in the patent looks like any other, but the bottom section sandwiches a touch-sensitive display between a glass keyboard and the bottom of the device.

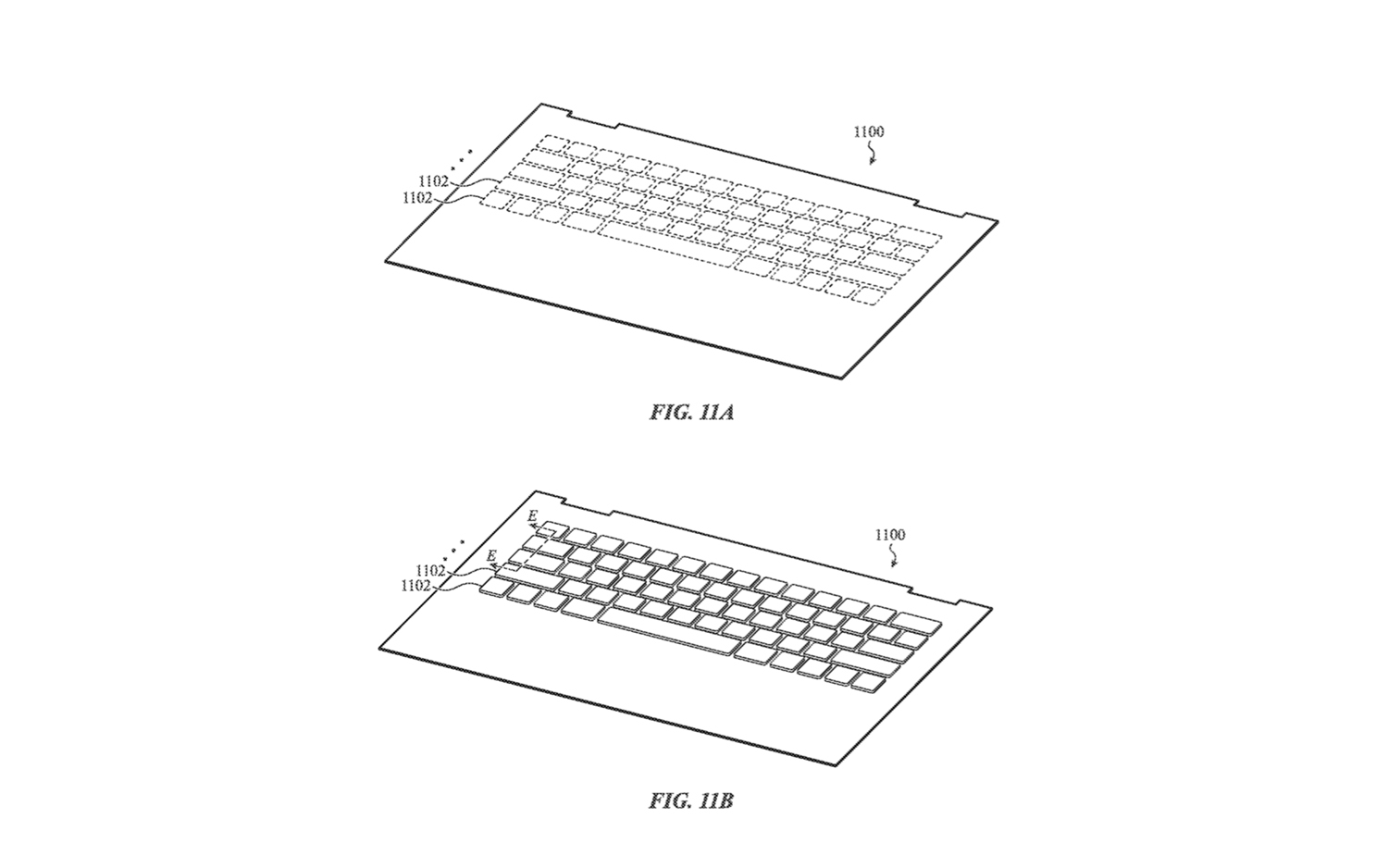

In essence, it’s going to be like your phone’s keyboard, except with a physical element on top. Phone keyboards do the job just fine. However, the key thing this patent is looking for is feedback from the keys. On a smartphone, you know if you’ve hit a key because the phone will briefly flash the character you’ve tapped and also vibrate. There’s very little feedback from just hitting the screen.

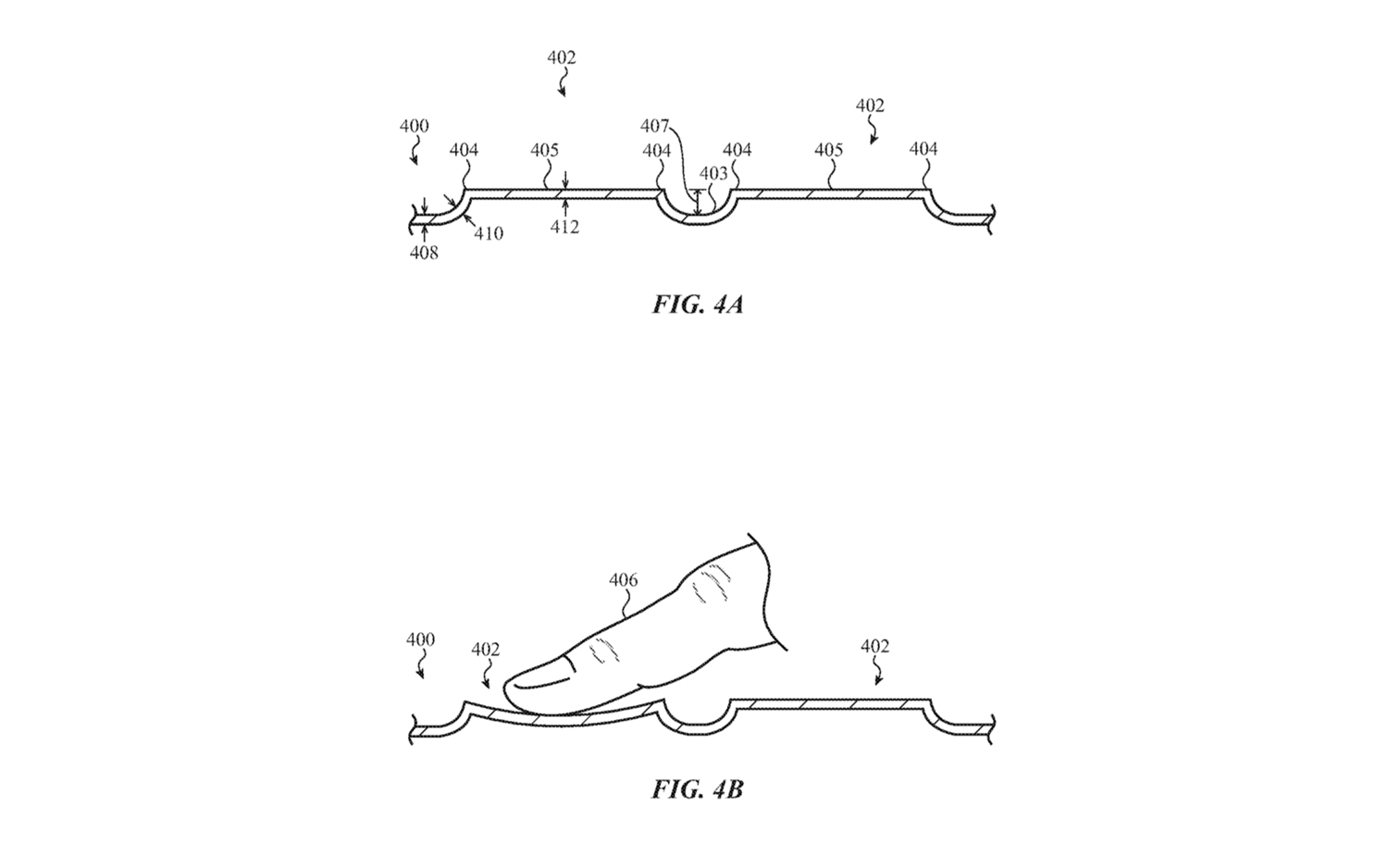

Apple’s solution is to have the glass keys bend or cause another element to buckle as you press keys, hitting the touch layer and giving you something between a touch screen and a normal physical key switch. Much of the patent is made up of possible designs for how the key would move when force is applied.

MORE: Apple MacBook Air vs. Dell XPS 13: Which Should You Buy?

A final set of considerations are made regarding enhanced feedback for key presses. Other than the act of pushing down on the key, the patent leaves room for the possibility of haptic feedback (smartphone-like vibrations for each tap), or "resilient members,’" either spring or collapsible dome structures within the key that make them harder to press, giving the user a similar feeling to typing on a normal keyboard.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

The MacBook range’s current keyboard design, using butterfly switches to give the keys a slim profile, has not well received with users, as these switches are prone to jamming if any dust finds its way into the mechanism. There have also been complaints about the space bar entering two spaces instead of one.

Your skeptic hat must be firmly on while looking at these designs; there’s no guarantee this will become part of any Apple product soon, or even ever. The whole glass keyboard layer does seem at this point in time an ambitious thing to actually make, but existing large dual screen and touch screen devices, like Lenovo’s Yoga Book, are asking questions about keeping the traditional physical keyboard.

Even if Apple’s design doesn’t pan out, it’s still a strong suggestion that the days of the keyboard as we know it are numbered.

Richard is based in London, covering news, reviews and how-tos for phones, tablets, gaming, and whatever else people need advice on. Following on from his MA in Magazine Journalism at the University of Sheffield, he's also written for WIRED U.K., The Register and Creative Bloq. When not at work, he's likely thinking about how to brew the perfect cup of specialty coffee.

-

Colif So Apple decides if their devices are going to bend in future, might as well patent it and call it a feature and not a bug :)Reply -

jsmithepa It had to happen. Last nigh episode of Orville they made rain on the bridge and if they still had mechanical keyboards, Starfleet IT would be screaming SPILL DAMAGE!Reply -

Solandri The first computer my parents bought for me was an Atari 400. It had a membrane keyboard, with a speaker underneath that would click every time you "pressed" a key, to simulate the feel of a keyclick.Reply

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Membrane_keyboard

Membrane keyboards sucked. The problem is that your sense of pressing a key seems to be based more on how much your finger physically moves, rather than how much pressure you exert. It's pretty easy to demonstrate. Close your eyes and move your finger by (say) 3 mm. It's pretty easy to do consistently. Now put an item weighing about 50 grans on you finger and try to guess its weight. It's really hard.

I think what's sending designers down the wrong path is that they're assuming all you need is haptic feedback to get a keyboard to work. It's not. The haptic feedback is just confirmation that you pressed the key. Since the feedback happens suddenly after you press the key, it's useless for helping you during the act of pressing the key. OTOH, the act of the key physically depressing gives you continuous feedback as the key moves down. Once your fingers learn that the key needs to be pressed x mm to activate, you can accurately and consistently predict how much further you need to press before the key will activate. That allows you to anticipate when the keypress will register, and begin typing the next letter even before you've typed the current letter.