Tom's Guide Verdict

This is the DNA test service to beat if your interest in genealogy drives your interest in your genes. Stick to that, and AncestryDNA can do a lot to tell your family's story.

Pros

- +

Good privacy options

- +

Can pinpoint ancestry down to individual counties (but don't count on this)

- +

Large user base increases your odds of finding missing relatives

- +

Amazing ability to weave DNA data and historical records together

- +

Two-step verification supported

Cons

- -

Limited test-kit purchasing options

- -

Add-on subscriptions can get expensive

- -

Listing of DNA traits is a mess

- -

Only just added health data

- -

Keeps your browser logged in for too long

Why you can trust Tom's Guide

The most widely used DNA test service has one job but offers to do two.

That is, AncestryDNA provides an immensely capable, DNA-powered heritage-tracing service that easily earns its purchase price. You can also pay extra to get some DNA-derived data on personal traits that's hard to browse and of limited value.

If you're curious about where in the world you came from, this is the test to get. If, however, you want to know what makes up you, 23andMe will probably serve you better.

AncestryDNA pricing and onboarding

The process at Ancestry starts with ordering a test kit: $99 for the core origins and ethnicity test, or $119 for a combination of that and personal-traits testing.

You can buy either through Ancestry's site or at Amazon. Since the former carries shipping charges of $9.95 (seven to 10 business days), or $24.95 (two to three business days) while Amazon offers free or cheaper shipping plus the occasional discount, the only reason to buy direct is to avoid telling Amazon that you bought a DNA test kit.

I bought one via Amazon. It arrived a day later than Amazon's estimate.

However you get the kit, you'll have to set up an account at Ancestry, which requires providing your name, email and password as well as a billing address.

You also have to consent to Ancestry's basic testing, then choose to approve or decline having anonymized genetic data shared for research purposes and finally decide if you want to be visible to potential relatives (as determined by DNA matching) on the service.

How the AncestryDNA Kit works

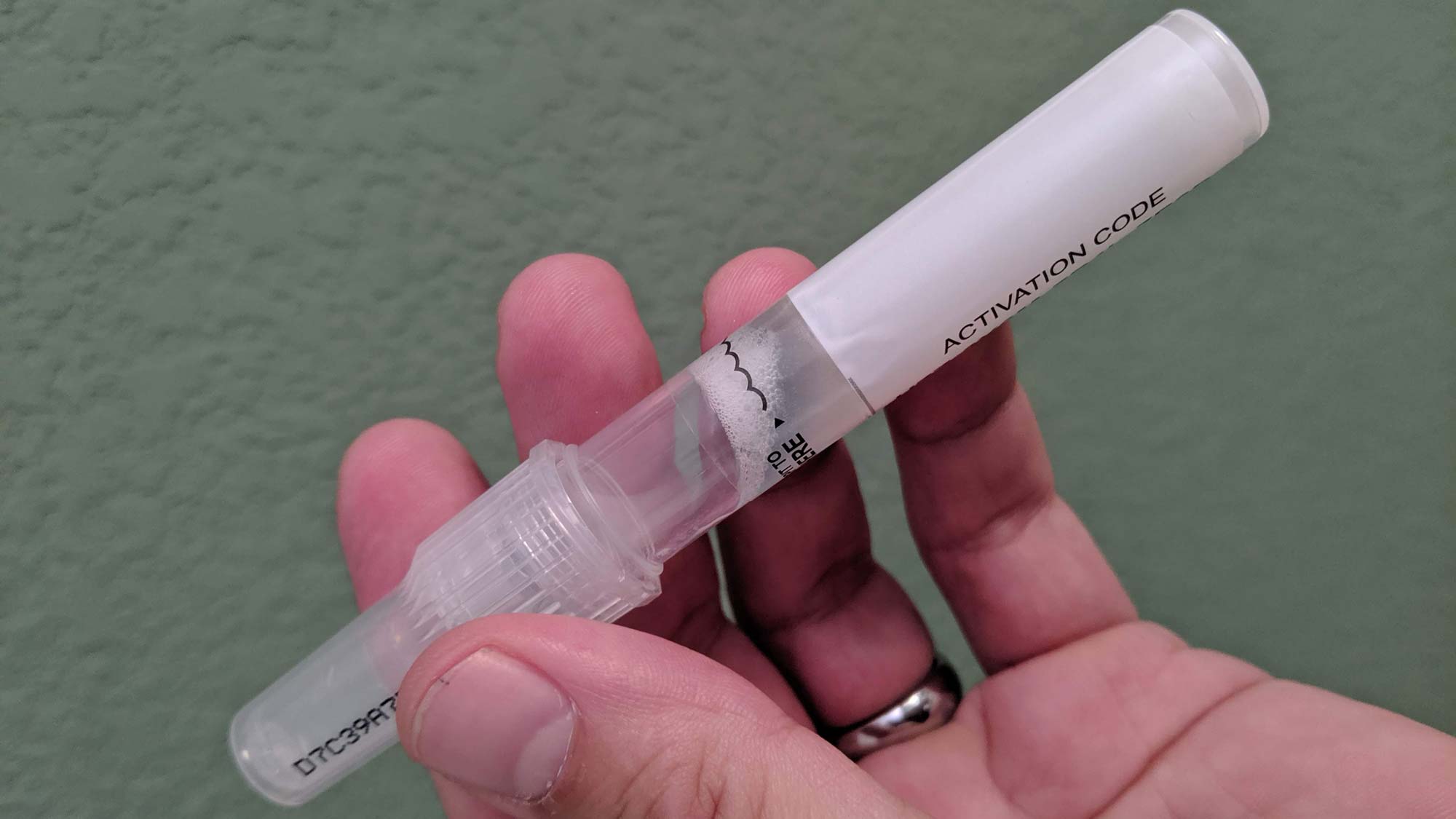

The kit itself features a plastic cylinder with printed instructions, the important part being: "Do not eat, drink, smoke or chew gum for 30 minutes before giving your saliva sample." It also features an activation code that you need to add to your account.

After that fast, you spit into this tube, screw on a top that will release a blue stabilizing solution (without an audible click to indicate you've properly sealed the tube, that may not be obvious), place the sealed tube in the sample bag and then put it in the pre-addressed, prepaid box. I trust that will be one of the strangest things you ever put in the mail.

Ancestry sent an email confirmation of the kit's arrival three days after I mailed it, with this advisory: "Your DNA results will likely take 6-8 weeks, but due to high demand, they may take longer."

An email nine days later reported that my results were in.

AncestryDNA heritage: Exploring your origins

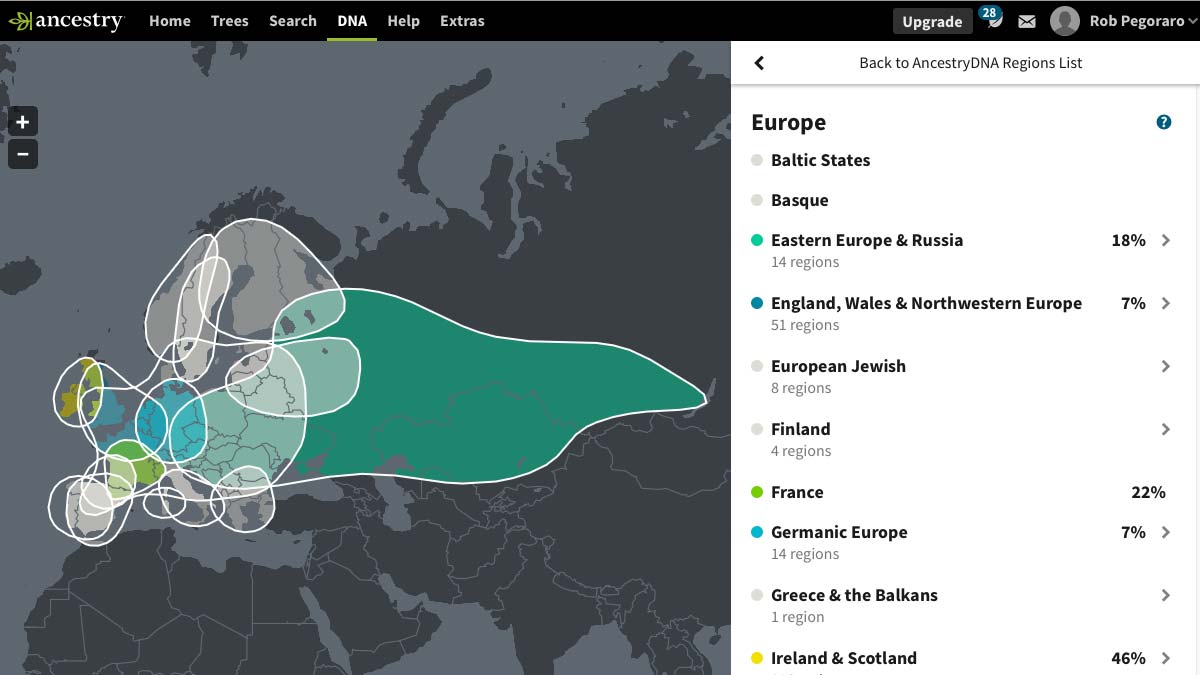

The most fascinating part — certainly the biggest potential time suck — of AncestryDNA is its exploration of your heritage. That starts with a map showing clouds of probability: The exact percentages shown, on inspection, can be much less exact.

For example, Ancestry's estimate that I have 8% Eastern European or Russian heritage (down from 18% after an October recalculation) came with this note: "Your ethnicity estimate is 18%, but it can range from 0-27%."

That overall figure seems correct, since my grandmother on my dad's side was Croatian. Ancestry's estimate that I'm 28% Irish or Scottish also seems about right: My grandmother on my mom's side was born in Ireland. Ancestry touts the ability to pinpoint ancestry down to county levels, but that specificity did not emerge in my own data.

Ancestry also reported zero Italian ancestry, contrary to all the records we have on my dad's side of the family. I don't know what to make of that.

"There are things like non-paternity," said Joann Bodurtha, a professor of genetic medicine at the Johns Hopkins Department of Genetic Medicine, when asked to comment about the generic possibilities for DNA tests to deliver results contrary to records. "It isn't impossible that the shoe salesman wasn't in town, you know."

My father, his brother and their parents are all deceased, so there's not much I can do to unwind that mystery.

One reason to think AncestryDNA may have a point there: Its reference database of 15 million customers and counting gives it the biggest sample size in the consumer-DNA-test business. On the other hand, it does not do mitochondrial or Y-chromosome testing, so it cannot trace paternal or maternal lines more than five generations back.

AncestryDNA U.S. Discovery and World Explorer services

Ancestry's earlier identity as a genealogy service shines in its ability to pluck out matching records from various databases. In minutes, it had surfaced such data points as my mom's father's military-service records and census data from my dad's childhood in Michigan. Now I know that people have been misspelling "Pegoraro" in America for over a century.

Plugging in all this historical documentation will cost you, however. Ancestry's U.S. Discovery service costs $19.99 a month, or $99 for six months, while its World Explorer, with access to non-American records, runs $34.99 a month, or $149 for six months. You're well advised to grab as much data as possible during your two-week free trial.

The power of crowdsourcing also shines through in Ancestry. With some 14 million users, per a Technology Review estimate, the odds are high that some of your relatives have already begun assembling a family tree. Ancestry can help you piggyback on those records with features such as ThruLines, which locates matching data based both on your DNA and family trees already on the site.

In my case, those odds were 100%: The day after Ancestry invited me to check my results, I got a text message from one of my cousins — now genetically verified as such — saying she’d seen my profile there.

AncestryDNA traits testing

Ancestry becomes less useful when it offers DNA guidance on 26 personal traits. Most are physical, such as the state of your hair (straight or curly? light or dark? subject to hair loss or not?), your propensity to develop a unibrow (really), and finger length (is your ring finger longer than your index finger, aka the "have you really looked at your hand, man?" question).

A second set can explain why you've never liked cilantro, or sneeze when it's sunny, or are especially sensitive to sweet, bitter or umami tastes. And the last batch estimates what sort of levels you have of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamins C, D and E.

This $20 option offers the possibility of enlightenment, but the presentation is a mess. There's no flat list of each trait as recorded, forcing you to click from screen to screen as if you're in the throes of a pageview-hogging slideshow.

AncestryDNA security and privacy

My initial setup at Ancestry ran aground when the site errored out after 1Password provided a 24-character password. But a 12-character password generated by that password manager did work, and the site did not reject auto-filled passwords afterward.

The site did, however, keep me logged in over long periods and even through browser and computer restarts, raising the risk of snooping on unattended and unlocked computers. I did not find a setting to cancel that, and activating its two-step verification — only provided via text messages — did not make the site log me out faster.

Ancestry offers the option of logging in via Facebook. We would advise against doing that, as the social network has quite enough data about all of us already.

Ancestry says it stores your genetic data without your name attached and encrypts it throughout. This company reserves the right to engage in behavioral targeting at other sites but provides an opt-out.

As for government curiosity, Ancestry's posted law-enforcement guidelines say it requires a warrant for the disclosure of any genetic information. Since early 2016, it has posted a transparency report adding up how often governments have demanded data about its customers; in 2018, it received 10 such demands in the U.S. and complied with seven.

AncestryDNA vs. 23andMe

Your motivation for taking a DNA test may drive your decision between AncestryDNA and its rival 23andMe more than the features and quirks of either service. If you want insights about your health, AncestryDNA only just began trying to cater to that market — its AncestryHealth service is provided through a network of doctors and is unavailable in New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island. But if you're seeking data about your heritage, Ancestry's ability to layer historical documentation on top of genetic information makes it unmatched.

That said, 23andMe offers a substantially better interface in many aspects, especially its treatment of personal traits. It also exceeds Ancestry's security, both in its default behavior and its support for two-step verification. But because 23andMe runs its full suite of tests, including for health risks, you need to be comfortable with its potential to create facts you may not want to know about, while AncestryDNA doesn't pose that risk.

Bottom line

Untangling your past remains the dominant use for DNA tests, and in that area AncestryDNA has secured itself some compelling advantages. It has the largest user base, meaning the best odds of locating long-lost relatives, it comes from a company that specializes in genealogy, and it offers the potential — at an ongoing extra cost — to flesh out your family tree with historical documentation.

But its initial upsell option of genetic-traits testing saddles you with an inefficient interface, and AncestryDNA’s new, add-on health service comes with its own limits. If not knowing what predispositions might kill you decades from now is more a feature than a bug, then AncestryDNA easily earns your business.

Rob Pegoraro tries to make sense of computers, consumer electronics, telecom services, the Internet, software and other things that beep or blink for a variety of online and print outlets.