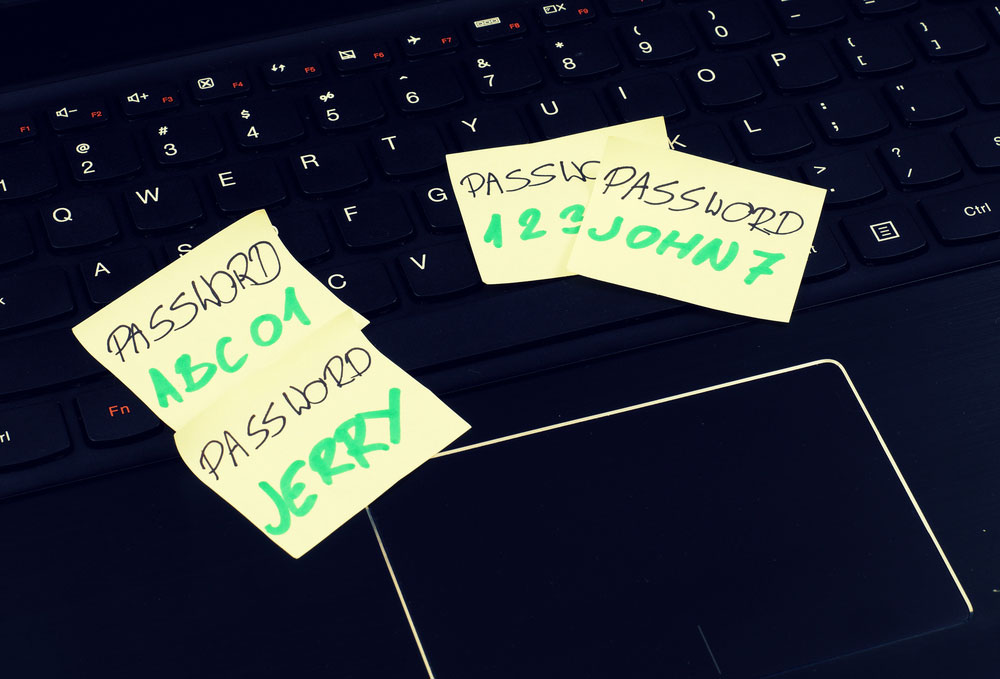

Are you one of those people? You know, the ones who use the same password for almost every website? You've heard that's a bad idea, but you think you're secure, right?

Do me a favor. Go to haveibeenpwned.com and enter your email address. Or tell a friend to. Chances are, you or your friend have had at least one instance of your personal information being exposed in a data breach. And you wouldn't be alone.

- The one password tip everyone needs to know

- Everything you know about 'secure' passwords is wrong

- Microsoft says password strength doesn't matter: here's why it does

The average computer is subject to a hacking attempt every 39 seconds, according to a University of Maryland study. The first entry point a hacker will try is almost always your password. And if you reuse a password from one site to the next, a breach at one site will often result in your account being compromised on others.

So what can you do to make sure your passwords are bulletproof? How can you limit the damage from data breaches? The best way is to never reuse passwords, and the best way to do that is by using one of the best password managers.

Old habits die hard

A recent Google study confirmed what most of us already knew: Many people will stick to using the same passwords, even if they know the passwords have already been hacked.

Despite warnings that their passwords had been compromised in data breaches, nearly 26% of users in the Google study decided to carry on with their existing passwords.

Some users in the Google survey said they thought the warnings and the password-reset process were confusing. Others didn't think a password reset was really necessary. Another survey showed that almost 83% of people use a single password for multiple websites.

For many people, poor password practice simply boils down to "security fatigue,"a weariness or reluctance to deal with computer security, often from being bombarded by messages reminding you to secure your information.

Don't count on others to protect your password

But you do need to take charge of your own password security, because you can't rely on anyone else. Some websites and online services still store user passwords as plain text. If a hacker gained access to the user database of one of those websites, your password and account details would be exposed instantly.

Most websites do encrypt passwords, but that doesn't solve everything. Hackers can crack the encrypted passwords, or "hashes," of weak passwords. They know that many people use simple words, or a combination of simple words, as passwords.

So the hackers run long lists of words through common password-encryption algorithms and save the resulting hashes. When there's another data breach, all the hackers need to do is look for hashes that match what they've already generated.

Understanding the security of the website you're dealing with is also important. A University of Cambridge study found that the worst security practices occur at sites with few incentives to keep their own content secure, such as media websites. Sites handling sensitive information, such as banking or messaging services, implemented better password security — but you can never be certain.

Alphanumeric passwords are not enough

You can create strong passwords by mixing letters, numbers and special characters. An alphanumeric password is, of course, better than a password that uses only letters. But if you're turning alphabetic passwords into alphanumeric ones by making obvious character substitutions, the results will likely be predictable and easy to crack.

For example, hackers know that many people will substitute the letter "o" with a zero ("0"), the letter "l" with a "1" and an "i" with an exclamation mark ("!"). If you do that, too, even your "complex" passwords might not be secure enough.

A common practice used by hackers to crack passwords is the dictionary attack. With this method, an automated script tries to get into an account by systematically trying every word in the dictionary as the password. The scripts can also try the most common number-letter substitutions, as detailed above.

To counter these "brute force" attacks, many websites lock out users for a limited amount of time after a certain number of wrong password entries. This anti-hacking defense mechanism is also found on iPhones, where the amount of waiting time gets longer with each wrong entry.

These prolonged account lockouts mean it can take years for a hacker, even one with the help of an automated program, to successfully break into an account.

Yet, even the strongest password can fall victim to a "keylogger," a program or device that can record everything you type into a keyboard. The logs of what you've typed are sent to a remote hacker, who can then access any password you have, no matter how strong.

Two-factor authentication

Using a password was once the only layer of account protection for you on the internet. Now smartphones or other devices can be added as another layer.

With two-factor authentication (2FA), you'll be asked for a second form of identity authentication when you log in to an account from a new device or location. If a hacker doesn't have that second "factor," then the hacker can't get into your account, even with your password.

The most prevalent form of 2FA sends a temporary passcode to your phone via an SMS text message or a smartphone app. There are also free authenticator apps, made by Google, Microsoft and several other companies, that can generate temporary passcodes right on the phone.

The second factor can also be a USB security key made by a company like Yubico or Google. These keys come in USB-A, USB-C or Lightning formats to plug into PCs and smartphones, and some also have NFC short-range radios to interact with older Android devices. A single key can be used to log in to dozens of online accounts.

Many services, such as Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Twitter, support security keys. The keys themselves do not store any user information, so if you lose one, it's almost impossible for anyone to discover that it belongs to you.

However, 2FA isn't the complete password solution, Hackers have found ways to intercept SMS messages bearing 2FA codes and to con victims into typing these codes into phony websites. Meanwhile, USB security keys cost between $15 and $70 each, depending on their features.

Password managers, more necessary than ever

The best way to keep your passwords unique and strong, and your accounts as secure as possible, is to use a password manager.

These programs can generate complex passwords and save them for you so you don't have to remember them at all. They can tell you when existing passwords are too weak and can suggest better replacements. Some of them can even change your passwords for dozens of different accounts at once in the event of a major data breach.

With a password manager, you'll need to remember only one password: the "master password" for the password manager itself. Think of it as "the one ring to rule them all" from The Lord of the Rings, and don't lose it. (Many password managers support security keys to protect the master password.)

You can try a password manager like LastPass for free to see if it's for you. Check out our list of the best password managers for more options.

Keeping ahead of the crowd

As we are introduced to newer services online, the number of online accounts that we have also increases. Instead of making account security a chore, the methods above make it easy. If you implement 2FA and a password manager and make sure you're not reusing any of your passwords, you'll be more secure than 99% of the population.

Next time there's a data breach and everyone else is rushing to change their passwords on multiple accounts, you can relax in the knowledge that you'll need to change only the password pertaining to the breached service.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Mir Ubaid is a contributing writer at Tom's Guide. He reports on the intersection of cybersecurity, privacy and public policy. His stories have also appeared on Al Jazeera English and Reuters. When he's not working, Mir spends too much time playing Counter Strike, where he's been perpetually stuck at rank Gold Nova 4 for the last five years.