DNA Test Kits: Everything You Need to Know

DNA test kits can help you learn more about your ancestry and your overall health, but they also raise concerns around privacy. Read this before you buy.

Unwinding the secrets of your heredity and health through a consumer DNA test — no doctor's appointment necessary — wasn't a possibility people even had to contemplate until a few years ago.

Now, these direct-to-consumer (DTC) DNA tests are a $100-and-up option from multiple vendors, and they're not just a possibility but also a potential problem. Buying a test online and mailing in a sample of your DNA may mean you learn things you'd rather not know — and it will create information that you probably won't want other companies to know.

All that doesn't make the answer to "should I take a DNA test?" an automatic "no." It does, however, mean that the response should never be an automatic "yes."

How DNA test kits work: Heredity, health or both

The basic process is the same for most DTC DNA test kits. You buy a kit in a store or order one online, and it arrives in the mail. You then collect a DNA sample (either by spitting into a tube or swabbing the inside of your cheek) and mail it in, and in a few weeks, you can see the results by logging in to your account at the service's site.

Those results arise after a lab extracts the DNA molecules inside the cells and then reads your genome for the tiny fraction of variants that essentially encoded you as different from every other person.

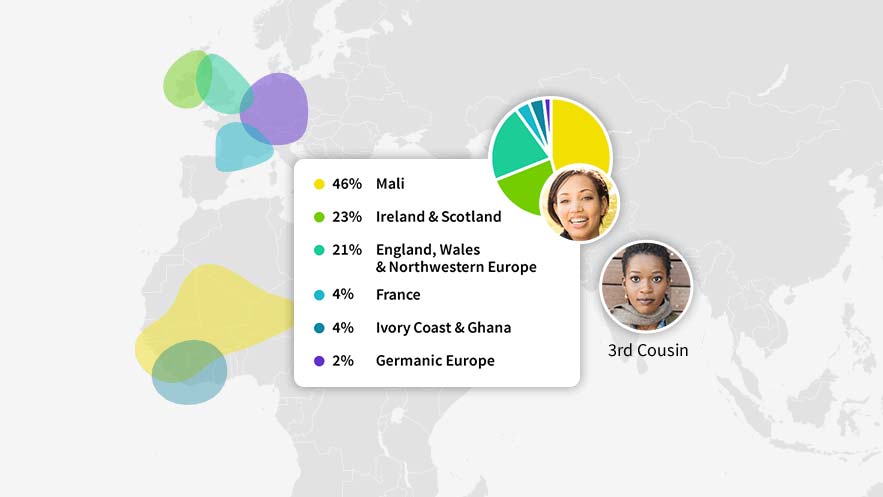

But not all consumer DNA tests look for the same genetic markers. Most tests emphasize the markers that can reveal your ancestry, looking for matches in a reference database to show where your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on came from.

That use has goosed most of the growth in DNA tests, with AncestryDNA the most popular service in this category. In February, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Technology Review estimated the company had sold 14 million test kits out of 26 million sold overall to date.

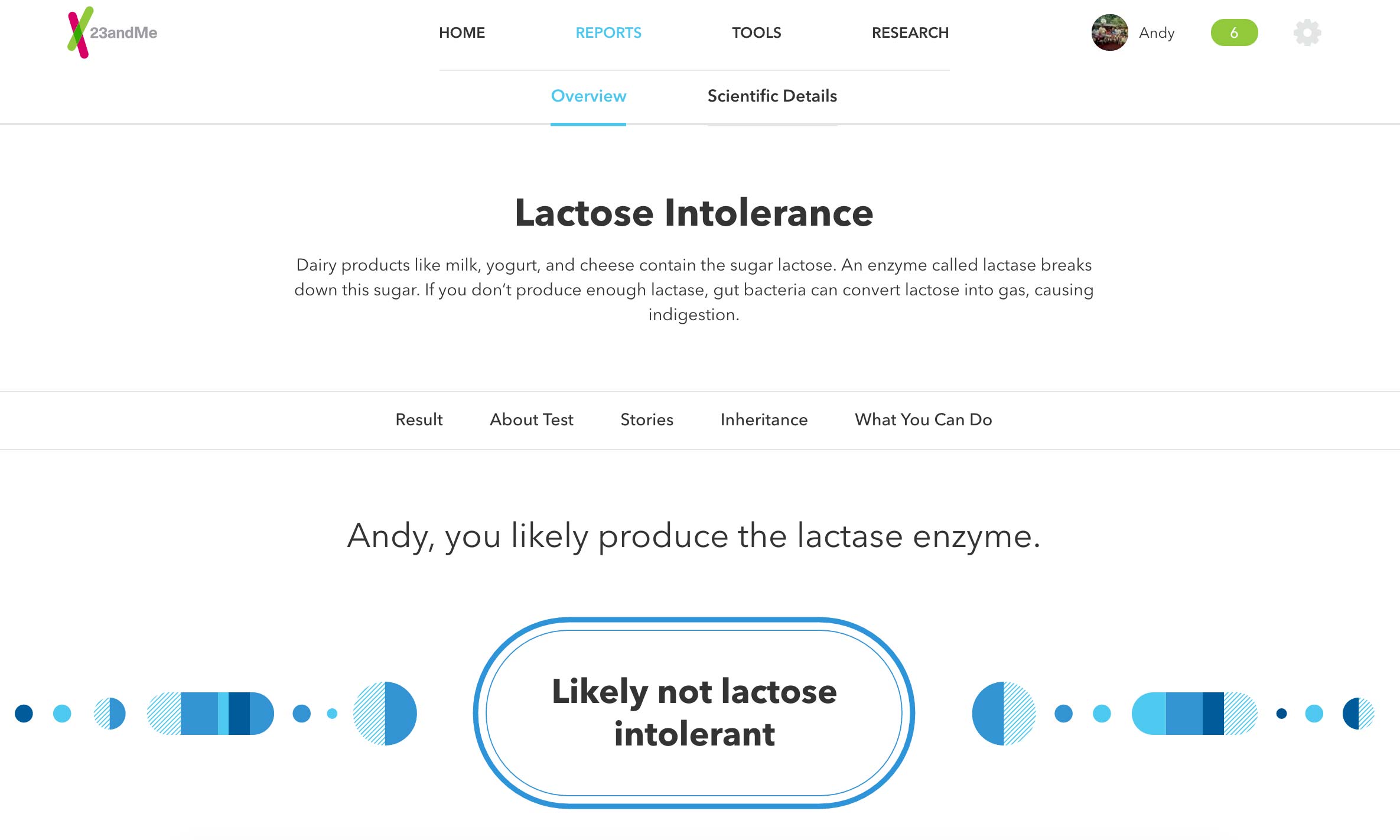

Your chromosomes can also encode for personal traits like hair color or aversion to cilantro (no, really), as well as such long-term health risks as breast cancer or Alzheimer's disease. That's the speciality of 23andMe, which has 9 million sales, as reported by Technology Review, and so may as well be the Pepsi to Ancestry's Coke.

That more sensitive health information will probably cost you extra; 23andMe, for example, charges another $100 for its Health + Ancestry DNA kit.

The remainder of the market consists of such smaller services as FamilyTreeDNA ($59), MyHeritage ($69) and Helix ($49.99).

DNA tests for ancestry: How accurate are they?

Ancestral DNA testing is a pattern-matching practice. The service will compare your variants to its own reference database — the larger that database is, the more reliable the results are likely to be — and estimate where in the world your ancestors originated. Those estimates can be precise, but it would be a mistake to put the same faith in every significant digit.

In January, the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. reported on identical twins who sent samples to five ancestry-DNA testing services, none of which reported the same ancestries for the two.

If your ancestors did not come from Europe, you are particularly likely to be misled by these tests, because their reference databases don't include enough non-European samples. Both Ancestry and 23andMe have been working to address that shortcoming, while some services — for example, African Ancestry — focus on particular non-European populations.

MORE: Best Nutrition Apps

If you want, you can also have the DNA-test service look for possible relatives among other customers who have also agreed to open their data to matching. You can then choose to contact these people through the service, as if it were a nonromantic Match.com in which people are seeking family members.

That is where things can get more interesting and dicey: Ancestry DNA testing doesn't decode as much of your chromosome as does testing for health issues, but it can still generate facts you may regret creating.

"People are finding relatives who they didn't know existed, and they're finding that they're not related to people that they thought they were related to, and that can create psychological issues that they're not prepared to deal with," said Jennifer Lynch, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco digital-rights advocacy organization.

"A friend of mine found a half-sibling that she didn't know existed, and then her dad did not actually remember ever being with this half-sibling's mother," Lynch added. (A paternity test later confirmed the father's involvement.)

The best-case scenario is more like one that a cousin of mine had: Ancestry told her of another cousin via my grandfather. My cousin and my mother were delighted to meet their newfound relative in person in New York and learn some new details about my grandfather's parents.

DNA test kit health screening: Potentially life-saving (and worrying)

The risks of analyzing DNA for your ancestry and personal traits remain far lower than the risks of having your chromosomes scanned for markers indicating future health risks.

If the report says your DNA doesn't reveal any long-term hazards, that's great. But if the findings suggest that you have an elevated risk of Parkinson's or Alzheimer's or another disease with no present cure, you now know something you didn't before but that you can't necessarily act upon.

"There are real mental-health questions about how individuals might react to certain health tests," said John Verdi, vice president for policy at the Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington-based research and advocacy group funded in part by tech companies.

Verdi cited the untreatable brain-cell-killing disorder Huntington's disease as one forecast that a DNA test can impose upon someone. "It's a pretty grim diagnosis."

A forecast could also spur you to take actions to ward off that fate, assuming you can afford what may be an elective procedure. See, for example, actress Angelina Jolie electing for a double mastectomy and the surgical removal of her ovaries and fallopian tubes after DNA testing revealed that she had exceptionally high odds of breast and ovarian cancer.

These kits leave you staring at results on a screen. And though you'll hopefully remember such generic counsel as 23andMe's reminder that "Other variables come into play, including nongenetic factors, such as your environment and lifestyle," these services don't provide much in the way of bedside manner.

For that reason, the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) has said that all DNA-test services that can yield "clinically meaningful" results should provide as much context as possible and point their customers to additional expertise.

That Washington group's latest recommendations read, "AMP strongly supports referral for genetic counseling services and the provision of educational materials to consumers of genomic testing."

DNA test kit privacy concerns: Incomplete laws

Unfortunately, you can't assume that the results of any DNA test you order won't go beyond you and your personal physician. The United States has no federal privacy law governing how companies can use your DNA test data, and even existing medical-privacy laws offer only incomplete coverage for genetic data.

In particular, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) declares that "a national and uniform basic standard is necessary to fully protect the public from discrimination," but that act covers only health insurance and employment. And even its insurance provisions exclude businesses with fewer than 15 employees and health coverage offered by the military, the Veterans Health Administration or the Indian Health Service.

GINA also says nothing about life insurance, disability insurance or long-term care.

A separate medical-privacy law, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act — or HIPAA, as in the form we've all had to sign before an appointment with a new doctor, often without reading — doesn't even govern direct-to-consumer DNA tests.

As Verdi observed, "What we are missing with genetic data is a sector-specific privacy regime." Lynch phrased things more starkly, saying, "These consumer genetic-testing services, they sort of exist in this wild, Wild West where they're not regulated."

(California residents will get much broader protection when the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, or CCPA, which does cover DNA data, enters into effect on Jan. 1, 2020.)

That means it's up to DNA-test purchasers to inspect the privacy policies and practices of the firms selling these tests. The key question Verdi cited: Do they require your upfront permission before any sharing of data with third parties, or do you have to opt out of a default setting to share data?

He noted that Ancestry and 23andMe both operate on an opt-in basis, which he noted exceeds the opt-out standard of the CCPA.

The latter firm does, however, share aggregate data with other businesses. "Aggregate" means that the information's been stripped of any details identifying you, then mashed up with equally anonymized data from others "so that you cannot reasonably be identified as an individual" from it. Last year, 23andMe signed a $300 million deal with the pharmaceutical firm GlaxoSmithKline, although customers still have to approve the sharing of their data in that effort.

MORE: Apple May Stop Police from Cracking iPhones

Both Ancestry and 23andMe also say they store DNA data separately from your personal information and encrypt it both in transit and while stored. That last step alone sets those two apart from the many, many companies that have left customer information unencrypted on their servers, leading to its compromise in a data breach.

Both of those DNA testing-kit services will also let you download your full data and then delete the company's master copy on request. But the two businesses part company in how they handle the original DNA sample you mailed in: 23andMe allows you to order the sample's destruction, while Ancestry will keep it after you delete your data unless you make an extra request for its disposal.

DNA test kits and law enforcement

DNA testing has become increasingly important in criminal investigations and sometimes essential to solving them. In April of 2018, for example, California police cracked a decades-old serial-murder case by uploading a long-stored crime-scene sample of DNA to a relative-finding site called GEDmatch that lets people upload their own DNA results.

That instance didn't involve law-enforcement investigators making private data public, but the databases of a commercial DNA-test service are a different matter. Ancestry and 23andMe say they require a warrant for any police query of their databases.

Those companies also document these queries (as well as national-security demands) in regular "transparency reports" that track how many times the businesses turned over any information.

Ancestry's annual transparency report says the company complied with 7 of 10 valid law-enforcement requests in 2018, none of which revealed genetic data, because all involved credit card fraud or identity theft. Meanwhile, 23andMe's latest quarterly report said that zero customer data was disclosed in the first quarter of this year.

FamilyTreeDNA, however, chose a different route when it began allowing police to upload crime-scene samples for possible matches — and the company did not disclose that policy to its customers. The business confirmed this policy only months afterward, when BuzzFeed News learned of it independently.

The company later explained that decision in a corporate post. FamilyTreeDNA said that police-created accounts have no more access to the company's database than any other paid user, so "they would not be violating user privacy and confidentiality."

At some point, FamilyTree DNA also deleted the transparency report it had posted, although the Internet Archive retains a copy. This report shows that in the first quarter of 2018, the company had disclosed no genetic information of any of its customers to law enforcement.

Are DNA test kits right for you?

Seeing sales that cut the prices of these DNA test kits by 40% or even 50% can invite quick clicks of a buy button, but this is the last purchase you should rush into. In some circumstances, you shouldn't even think of buying one.

Verdi, for instance, drew up on his past experience as a class-action lawyer to advise people facing possible legal entanglement to decline DNA testing. "I would imagine circumstances where attorneys would urge clients not to generate any new health information," he said.

He added that he has not used any of these services either.

"I am, for better or worse, not a heredity geek," he said. The medical aspects don't appeal to him, he said, as somebody in apparently excellent health, either. "No doctor has indicated to me that I would benefit from such a test."

MORE: 4 Ways the Apple Watch Could Step Up on Fitness

Lynch hasn't taken a DNA test either and said that potential customers should remember that much of their DNA is identical to that of close relatives, who may not want it shared. "If you upload your own information, just by default, you have entered other people's information in the database."

But she still declined to say that nobody should investigate what their DNA can teach them about their family history and future health.

"People have their own reasons for using these kinds of services," Lynch said. "That's a decision that everybody has to make."

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Rob Pegoraro tries to make sense of computers, consumer electronics, telecom services, the Internet, software and other things that beep or blink for a variety of online and print outlets.