Fire Emblem: Three Houses and the Illusion of Choice

It's all about being a people-pleaser

Fire Emblem: Three Houses is an incredibly fun and frighteningly addictive tactical RPG -- it even earned a spot on our best Switch games page. That said, it’s not a true role-playing game.

Instead of controlling the narrative and shaping your character's personality, you take control of Byleth: a glorified panderer, and more importantly, a bad professor. All of this is facilitated by the choices presented to you, and it’s the linearity of those choices that make Fire Emblem feel like a test taking simulator.

The illusion of choice

With a few obvious exceptions, such as choosing your house, the decisions you make in Fire Emblem: Three Houses are either right or wrong -- not to be confused with good or evil, but simply a pass or fail question. If you choose the incorrect dialogue option in a conversation, you’ll lose support points with the character you’re talking to. Receiving support from an NPC means you gain certain benefits when you’re next to them in the field, so your goal throughout the game is to gain the support of your allies.

What makes this so challenging is that the choices you have to make are based on how well you know the character you’re talking to, of whom you literally just met. This game of multiple choice got so frustrating that I gave up and Googled some of the answers because I didn't want to run the risk of reducing the support I already built up.

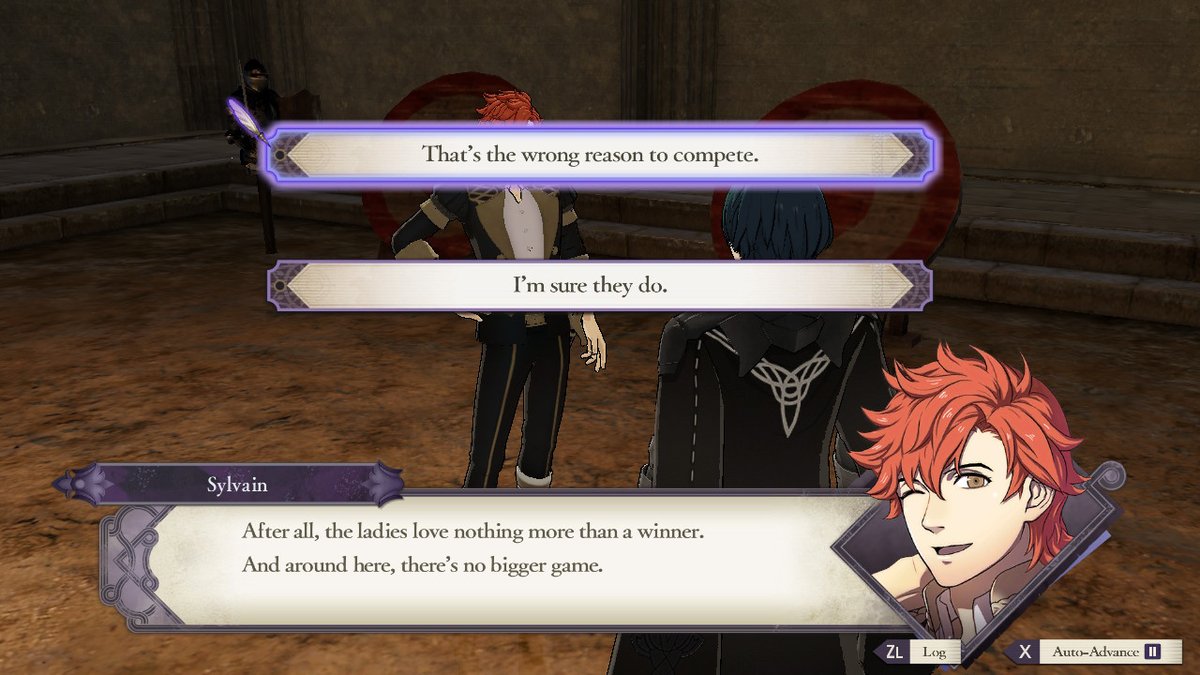

Because support points are at stake, the conversations are less about roleplaying your personality, and more about adhering to whatever wild nonsensical point of view the character you're conversing with has. Byleth runs around campus appealing to every student's wacko personality rather than cultivating their own and being the voice of reason, making them an awful professor.

One of the best examples of this is when there are two students complaining about each other in the Dining Hall. Instead of setting them straight, like a good professor should, the correct choices were to agree with each of their points of view. I told both students, separately, that they were right and that the other student was wrong. Who even gave me my degree? Oh, that’s right, I don’t have one.

Another example was when Bernadetta, an introvert, was locked in her room, and to get her to talk to me I had to say “Hey, what's this cake doing out here,” which was the right answer, but an outright lie. What kind of monster would lie about cake? Nevermind be rewarded for it.

Some of the choices are easy enough to suss out, but it gets difficult when you're stuck between two equally sincere answers like "You seem a bit down" and "What were you thinking about?" Nothing is wrong with either of them, and both would eventually lead to the same place in a real life conversation, but "You seem a bit down" is the only one that'll net you support.

Decisions that matter

I recently came off playing The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, an RPG in which I felt the weight of every choice, whether it was contained to a small tavern or affected an entire kingdom. The Witcher immerses you with every piece of dialogue because your choices not only spice up the conversation, but they affect the overall outcome. Choices in Fire Emblem do neither.

Most conversations start and end leading to the same outcome, regardless of the choice. Games like The Witcher and the Divinity series excel in doing the exact opposite, which is why they’re so beloved.

To dive a little deeper, the dialogue choices in Fire Emblem also start and stop with whatever you're shown in the prompt. Your character doesn’t bother to expand beyond that one snippet of dialogue in text, nor is there a voice over to help deliver the lines. (This is especially jarring since Byleth's combat lines are voiced over).

This makes a decent portion of the game feel like a test-taking simulator. And what’s worse, it doesn’t stop with conversations. There are mini-games too.

Tedious tea

After sinking 20-plus hours into Fire Emblem: Three Houses, I am knee-deep in the oh-so-epic Tea Party portion of the gameplay -- you know, the part where you can invite one of your students for tea and you have to play an arbitrary guessing game to deduce what they’re interested in talking about.

When you choose to roam the campus in your free time, you can spend activity points to take part in a Tea Party, which allows you to gain more support points than you typically would in a casual interaction -- given that you know what your plus-one is interested in.

This minigame consists of three conversation starters and one reaction, which acts as a bonus if you pass the first three. I kid you not, I have a text document on my phone filled with correct answers specifically for Tea Parties that I’ve gathered through trial and error -- just one character has accumulated 24 separate correct answers, and that’s only from my personal findings.

Not only does this mini-game suffer from linearity, but it also doesn’t deliver on the interesting conversations meant to be had over a cup of tea. Once you select a topic, like “Tell me about yourself,” the character you’re talking to replies with a short, predetermined response. So getting to know one of your students or colleagues really becomes just a frivolous minigame with nothing to offer, apart from support points.

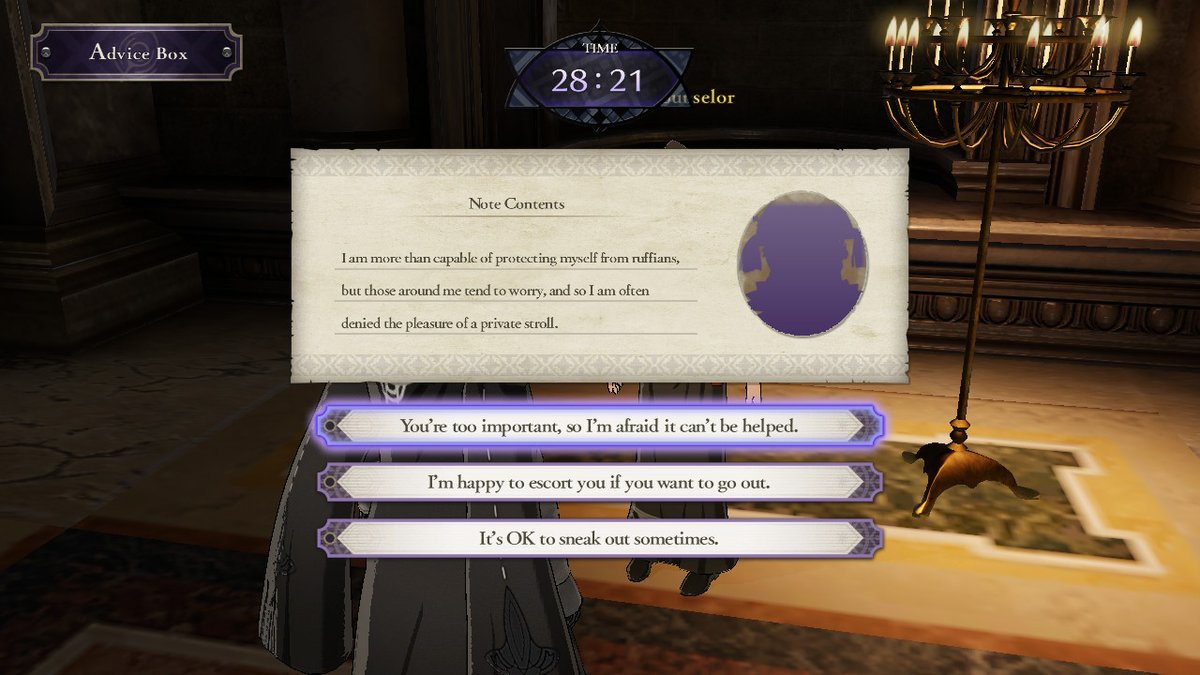

Another wonderfully crafted minigame is the Advice Box, which is a stripped down version of Tea Party that focuses solely on giving a character (unknown at the time) advice. Once you fail or succeed, the character’s face will be revealed. This is almost worse than Tea Parties in that you don’t know who you’re advising when they ask a question. Sometimes it's obvious, but other times I’m driving myself nuts trying to figure out whose broken personality I’m supposed to be appealing to.

Bottom line

Fire Emblem: Three Houses excels as a strategy game, but when it comes to finding its footing as a role-playing game, it falls so hard that it breaks the immersion. When I say Byleth is a bad professor, it’s not just to be cheeky -- Byleth is the sad result of shallow character development.

The main character is used only to validate the beliefs of other characters, and while there are key choices that shift the narrative, those ultimately don’t change your character’s personality. You’re not roleplaying a character of your own device, but one that incessantly has to please everyone; One so devoid of personality that they take on the disposition of the people they interact with. Fire Emblem: Three Houses is not a role playing game; it’s a glorified test-taking simulator.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.