Nier Replicant's Yoko Taro understands that life is a comedy. At least, that’s what I can surmise, based on the answers he gave to my interview questions. His answers suggest that, no matter how hard one tries to influence the world, that effort often devolves into the absurd. This Camusian sentimentality permeates his work, where he often makes rash narrative justifications just to link disparate threads, rather than just start fresh. He brushes off any deeper meta analysis by fans or critics as strained interpretation. I can only imagine his blasé expression as he answered my questions forwarded to him by Square Enix’s American PR team.

Why did I trouble myself to interview a man who doesn’t want to be interviewed? It’s because I find his worlds to be some of the most bizarre, avant-garde and philosophically dense in gaming.

Last week (April 23) saw the release of Nier Replicant ver. 1.22474487139… It’s a “version upgrade” — not a remake or remaster — of his 2010 title, which initially debuted to middling reviews and less-than-stellar sales. Our review was decidedly more positive, and the new version of the game currently sits at an 83 on Metacritic. Its sequel, 2017’s Nier: Automata, completely flipped Yoko Taro's fortunes, becoming a critical darling and a commercial success.

The Nier series is a mish-mash of genres, with outstanding action gameplay and an enthralling score. Automata’s subversive narrative served as a fascinating critique of the meaning of God, our own existence, and the issues and causes we fight for. Its on-the-nose callbacks to the giants of philosophy may have been heavy-handed, but its world was rich in mystery and lore. It’s one of those games that’s so drenched in ingenuity that it quite literally obfuscates your own understanding.

Plus, it has hot androids in skimpy outfits.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Square Enix wasn’t able to fly Taro, producer Yosuke Saito and composer Keiichi Okabe out for a press tour. Since I couldn't interact with them in person, I wasn't able to pick up on the subtle nuances of a face-to-face discussion. Instead, I had to email my questions, which Yoko Taro could have easily dismissed.

Not that a face-to-face conversation would have helped.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

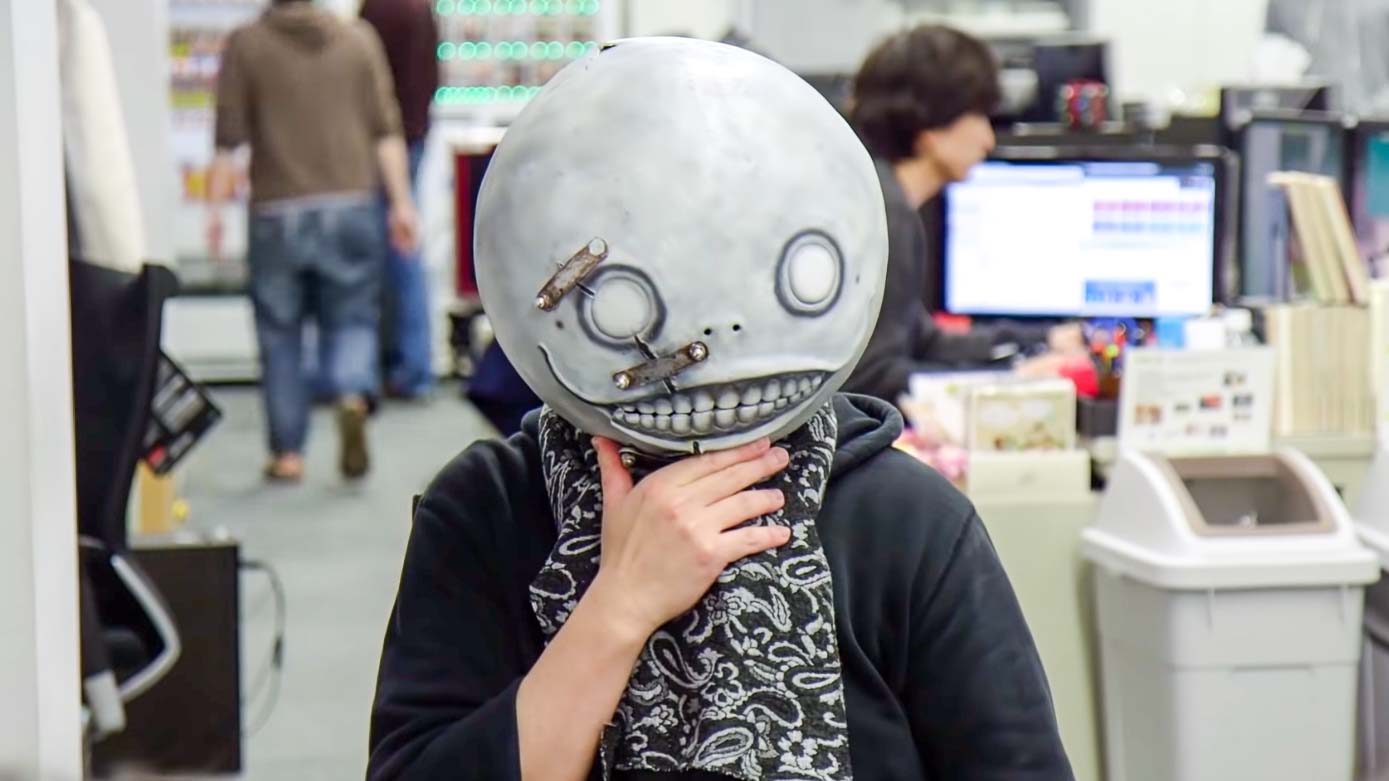

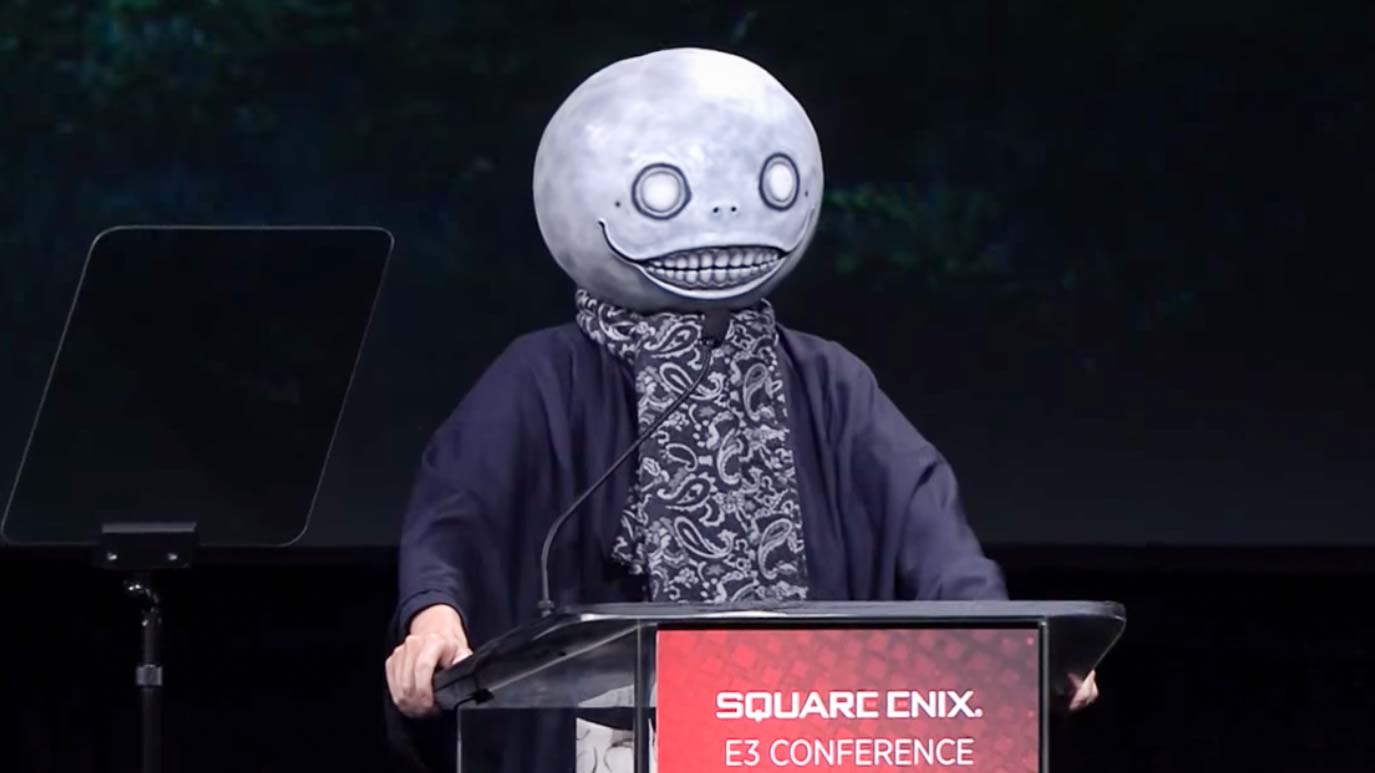

Yoko Taro, a Japanese game designer, is an odd character. He conducts interviews wearing a giant mask, and generally acts in a manner that can be best described as expressive, yet introverted. In an interview with Kotaku, when asked why he wears a mask, Yoko Taro said, “when you find out that the person writing pornographic novels is an older gentleman, you kind of lose that excitement.” He went on to add, “some people might lose that kind of expectation or excitement toward a game if they find out who’s actually behind it.”

Yoko Taro has a wall around him, and that mask makes it all the more difficult for journalists to suss out his feelings.

In video interviews, he can equally be contemplative and jumpy. It’s often difficult for journalists to get a straight answer out of him. He’d rather joke and quip than engage in a discussion, although he’s clearly capable of having an intellectual back-and-forth. He has a wall around him, and that mask makes it all the more difficult for journalists to suss out his feelings.

“I feel like my personality became twisted after being dumped like crazy by girls when I was young,” said Yoko Taro in an email interview with Tom’s Guide when asked about the depressing storylines throughout Replicant.

Taro is also humble to the point of self-deprecation. He often feels that he brings very little to a project — that instead, it’s his young and dynamic team of developers who pick up much of the slack. While his games are rich with quandaries and existential ruminations, he himself brushes off praise for the stories he puts together.

Replicant takes place in the year 3,361, years after an inter-dimensional catastrophe infected the world with disease. This illness cripples society and brings civilization back to the days of castle walls and candle lights. Yet, that disease is actually linked to Taro’s previous game from the PS2 generation: 2003’s Drakengard.

The first Drakengard game had five different endings. One of those endings was meant to be a joke, in which the final boss transports to another dimension (a modern-day Tokyo), where your character must defeat it. Upon finishing the fight, the final boss turns to ash. Unfortunately, that ash causes the plague that nearly wipes out humanity in the Nier universe. It’s a very roundabout way to link a game about talking dragons to one with androids in revealing leotards.

That fifth ending from Drakengard was meant to be a joke — nothing more than a referential callback to Evangelion, an anime series that was popular in the early 2000s. But this “backwards-scriptwriting,” as Yoko Taro calls it, is a technique he revels in. In some sense, deciding on the ending first and writing the narrative around it fills Yoko Taro's story threads with suspense and intrigue. Playing his games multiple times to get the true endings allows players to consider their actions with the benefit of hindsight, now that they know what the outcome will be.

Moving ahead, Nier: Automata takes place in the year 11,945. This is so far into the future that humans don’t even live on Earth anymore, choosing instead to reside on the moon. Meanwhile, alien-made robots have taken over the planet. To recap: the death of an inter-dimensional being infects the modern world, sending humanity into the dark ages over the course of 1,300 years. Humanity later escapes to the moon 8,500 years after that so androids can fight alien robots on Earth.

The worlds that Yoko Taro has made in each one of his games, all seemingly connected, are highly imaginative. Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy is pervasive throughout both Replicant and Automata. But when pressed on his predilection for philosophical admiration, Yoko Taro deflected.

“You’re reading too much into this. Yoko is only ever thinking shallow thoughts,” said Yoko Taro, who refers to himself in the third-person.

But there was a time when Yoko Taro was more forthright in his inspirations. The story in Replicant was inspired by 9/11 and the Iraq War, and how societies can create enemies to justify violence. In the early 2000s, Yoko Taro noticed that games often glamorize and gamify killing, such as congratulating a player for defeating 100 enemy soldiers. In a video posted on PlayStation’s official YouTube channel, Yoko Taro, who speaks through a sock puppet, discusses the strangeness of congratulating players on extreme levels of violence. For example: A serial killer gloating about his hundredth victim would not be a cause for celebration. Instead, society would call that person insane.

During the Iraq War, as Japanese media was reporting on terrorist organizations and the violence occurring in the Middle East, Yoko Taro came to a different conclusion:

“You don’t have to be insane to kill someone. You just have to think you’re right.”

It was in developing Drakengard that Yoko Taro, somewhat naively, believed he could exact societal change through his narratives. This was at a time when a large portion of the gaming audience was still young, and when banner franchises from Sony included kid-friendly titles such as Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon.

But even if Drakengard were rereleased today, gaming continues to occupy a lesser place in media criticism. Critics view gaming as either too intimidating, too othering or simply not worthwhile. (I refer here to larger single-player, narrative-driven games, not quick on-the-go mobile puzzlers.)

When asked if Replicant is a commentary on either American or Japanese society, Yoko Taro felt there was little use in answering.

“I have failed before at changing the world through games, and I continue to fail now,” said Yoko Taro. “But I still believe in the potential that lies within games, and I dream that someone new and young will break through for us.”

Contradictorily, while Yoko Taro wants games to be able to influence the world in a positive way, he himself isn’t totally comfortable with fame. When asking him what he makes of his post-Automata celebrity, he quipped, “no matter how much success I achieve as a video game director, I am not popular with the ladies. The world is so full of despair.”

(I should note that Yoko Taro’s lamentations regarding the opposite sex are somewhat exaggerated. The man is happily married to video game artist Yukiko Yoko, known for her work on the Taiko no Tatsujin rhythm game series. She also worked with him on Drakengard 3.)

His quirkiness aside, Yoko Taro has found a benefactor in Yosuke Saito, a producer and lead at publisher Square Enix.

“I think the reason Square Enix supports me is because producer Yosuke Saito, who I’m close with, won in a fierce political struggle that took place within the company and became an executive,” said Yoko Taro.

A Square Enix PR representative did clarify that Yoko Taro was joking here. Even then, Saito has shared a similar sentiment in the past.

"I said very strongly, I said, 'If you don't let me do this project, I'm going to quit the company,'" said Saito in an interview with Engadget, recalling how Automata came to life.

It’s not just Yoko Taro and Saito who have banded together for the better part of the last two decades; so has composer Keiichi Okabe. Think of Okabe as Yoko Taro’s Hans Zimmer. The music in Drakengard and Nier often receives the same reverence as Yoko Taro’s stories and settings.

“The world of Nier overflows with despair and sadness, but there is also a contradictory feeling, similar to a faint sense of hope or love" — Keiichi Okabe

The music in both Nier titles wavers between ominous operatics to more pop-inspired vocals, with jazz progressions and diminished chords. A fictional language, made up Scottish Gaelic, Spanish, Italian, English, French, Portuguese and Japanese elements is used throughout, sung wonderfully by vocalist Emi Evans.

In an interview with Original Sound Version, Evans said Okabe “wanted me to image [sic] how our languages of today would sound after thousands of years.” Okabe opted for Western-sounding languages as it felt more fictional and far removed from the real world. This is opposed to using Eastern languages, which “evoke the feeling of an everyday and very real world.”

“The world of Nier overflows with despair and sadness, but there is also a contradictory feeling, similar to a faint sense of hope or love,” said Okabe in an email interview with Tom’s Guide. “I created the tracks with the hope of including those multifaceted human emotions.”

While the trio do take game development seriously, Yoko Taro especially likes to keep things lighthearted. During a panel discussion at PAX East 2017, he revealed that 2B, the goth-lolita-fashion-clad protagonist of Automata, was not meant to be sexy at first. But upon receiving the initial designs from artist Akihiko Yoshida, Yoko Taro mentioned that “if the modeler can’t make her backside — her behind — look as exceptional as it does in the 3D model, they’d be fired.”

This same kind of ribaldry extended to how Yoko Taro engages with fans. Following the release of NieR Automata, images began circulating online of graphic details of 2B’s rear-end when looked at from a specific camera angle. Yoko Taro, instead of quelling the internet by claiming the image was doctored, opted to inflame. On Twitter, he lamented that due to the controversy, many obscene images of 2B were being made, and it was becoming too difficult to gather them all. He asked fans to compile it into one large .zip file for him to peruse. The internet, of course, obliged.

In a follow up Tweet, as translated by Niche Gamer, Yoko Taro stated, “When I said that I wanted people to gather images of 2B and put them in a zip file for me, the tweet got all kinds of exposure. Now people are actually collecting them. The internet is amazing.”

Yoko Taro’s aloof attitude is more of a front, from what I can tell. He might claim, as he did at that PAX East panel, that "I was drinking beer all the time, so I essentially didn’t work much." Yet, that’s not the sense I get from Saito, or the other interviews I’ve read regarding working with Yoko Taro.

"I love how he approaches creating so earnestly," said Saito in an email interview with Tom's Guide. Although he added, "I hate how he doesn’t buckle down and get serious until the last minute in our schedule." So maybe there’s some truth to Yoko Taro drinking too much.

Another aspect that defines Yoko Taro’s games has been the lack of funds they receive during development. His games don’t share the enormous production budget of last year’s Final Fantasy VII Remake, which reportedly cost more than $100 million to make. While Square Enix has never confirmed the budgets for Nier Replicant and Automata, we do know the latter title’s finances were too tight for any meaningful DLC. But fans have appreciated how much heart there is Nier and Drakengard, regardless of B-tier budgets.

"I feel the restrictions constantly, but no matter how much money is put in, there will always be restrictions that come up somewhere. Therefore, whether we were to have $100 million or $10,000, I'll just work hard at my job and do what I can."

Yoko Taro’s shtick of constant sarcasm and wisecracks should be grating. Yet, Saito, Okabe and the rest of Square Enix continue to support him. I think it’s because they genuinely like him. In a society that can be very rigid in expectations, Yoko Taro opts to be jovial and unprofound.

Even with a mask on, it relieves tension in a room and puts people at ease. Yoko Taro seems to feed off the reactions he gets from his colleagues, the audience at a panel and the poor interpreter that has to translate his unfiltered perversions into English. The comments section of any YouTube video featuring Yoko Taro will only sing praise of his jests, calling him an international treasure.

It’s often said that comedy and tragedy are two sides of the same coin. Clearly, Yoko Taro has reserved tragedy for his games, because in real life he’s having too much fun.

Imad is currently Senior Google and Internet Culture reporter for CNET, but until recently was News Editor at Tom's Guide. Hailing from Texas, Imad started his journalism career in 2013 and has amassed bylines with the New York Times, the Washington Post, ESPN, Wired and Men's Health Magazine, among others. Outside of work, you can find him sitting blankly in front of a Word document trying desperately to write the first pages of a new book.