iPhone security hole lets apps access your private data

iOS’ clipboard is wide open for any snooping app or widget

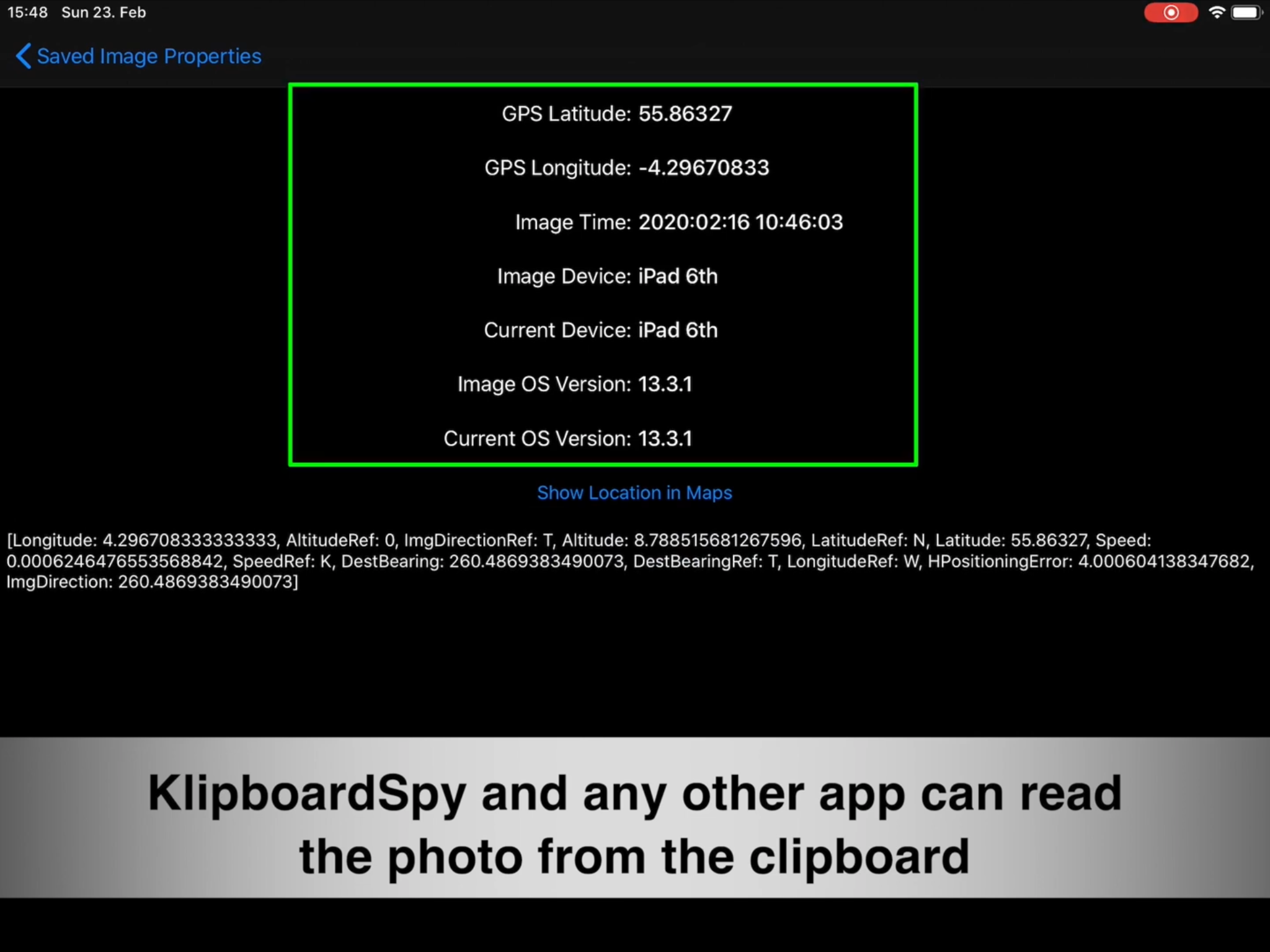

Any iOS app can silently read any confidential information from the clipboard even if the app doesn’t include any copy-and-paste functionality, according to a new report. This opens the door for a snooping app to get information (such as your location), no matter what its permissions are.

The warning comes from Mysk (via 9to5mac), a security firm that developed both an app and a widget that can silently access anything you copy in iOS.

- iPhone 11 review: the best phone for the money

- Here is the best antivirus you can get

- BREAKING: iPhone 12 will gain new multitasking powers with this upgrade

How this vulnerability works

Mysk's app — called KlipboardSpy — simply works by constantly monitoring the contents of the iOS clipboard and analyzing them. If you copy an image, for example, it will get its metadata and dig for location information that will pinpoint exactly where you took it (and potentially where you are any given time). As soon as you open the app, KlipboardSpy will tell you about any information it can find.

In the case of the widget, as long as the widget is active — like in the iPad’s home screen — your clipboard data will be accessed and analyzed.

It’s that simple, because this is what iOS’ clipboard functionality is designed to do.

- Can a free iPhone VPN match up to paid versions?

Is this a real risk?

Mysk’s app and widget inform the users about its actions and works like any other iOS app. Like KlipboardSpy, many apps constantly keep an eye on the clipboard to offer added functionality. When you open an app or have an active widget, they can prompt actions based on what is copied. That happens because this apps read the clipboard content in the background.

But if this happens by design, is it really a risk?

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

After being informed by Mysk, Apple dismissed any potential threat. The company alleged that this is how clipboards are supposed to work not only on iOS but also on macOS.

However, there is a case to be made that free access to the clipboard fundamentally affects the security of the entire system and your privacy. Passwords, location, images, and any other copied data could be easily and silently shared by a rogue app or widget posing to be something else without the user ever noticing.

- More: Keep your sensitive data protected with the best iPhone VPN

The case for limiting clipboard access

Plenty of apps have avoided Apple’s security filters on multiple occasions. And the same could be said about Google and its faulty Play Protect.

So if apps can pass Apple and Google’s safety system, why should we assume that having free access to the clipboard is fine?

Apple already asks users to give app permissions to access things like location data, but an open clipboard is a clear path to access location data without any limitation. The same could be said about any sensitive information that could be copied.

It seems there is a good case to make clipboard access an specific user permission, just like we grant permissions to access location, microphone, camera, photos, or stored files. It may seem like a pain because we have become so used to have this functionality always on, but when you think about it, a large number of apps shouldn't need access to the clipboard at all.

There’s no reason for not adding a user permission to an app’s clipboard access. It will just result in an operating system with an extra layer of security and privacy. And that’s always a good thing.

- More: Don't get caught out - browse the best mobile VPN apps

Jesus Diaz founded the new Sploid for Gawker Media after seven years working at Gizmodo, where he helmed the lost-in-a-bar iPhone 4 story and wrote old angry man rants, among other things. He's a creative director, screenwriter, and producer at The Magic Sauce, and currently writes for Fast Company and Tom's Guide.