How to play Dungeons & Dragons online with Roll20

Roll20 can help you play Dungeons & Dragons online

Playing Dungeons & Dragons online can be a challenge, but Roll20 is a tool that can help make digital adventures feel seamless. Since many of us are stuck at home right now and craving a bit of social contact, tabletop RPGs are arguably just the pastime we need.

Not only do you get to escape into a fantastical world and solve someone else’s problems for a while, but you get to do so with your friends. If you’ve been playing D&D or a similar RPG in real life, now is the time to take it online — and if you haven’t been playing, now is the perfect time to start your own campaign.

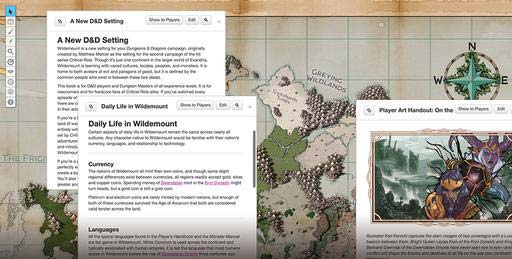

The only trouble with playing Dungeons & Dragons online is that the game is definitely designed with a physical tabletop in mind, with real people gathered around it to roll dice, move miniatures and collaborate on outlandish plans. This is where Roll20 comes in. This free program provides everything you need to run D&D — or almost any other tabletop RPG — right from your computer. You can build maps, customize character tokens, roll digital dice and even incorporate extras like music and private notes.

Roll20 can be a little abstruse, particularly if you’re new to playing RPGs online. As a player in one Roll20 game and a Game Master in another one, I’ve compiled a few tips to help new players get up and running with this powerful tool.

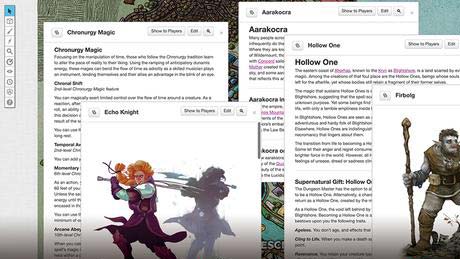

One important note: While Roll20 is optimized for Dungeons & Dragons Fifth Edition, it’s technically a system-neutral tool. You can run just about anything in it — some games have even their entire rule sets to Roll20. We’ll talk more about that later, but the bottom line is that D&D is just one possibility among many.

Getting started in Roll20

I’d say that the first thing you need for Roll20 is a group of friends who want to play an RPG with you — but that’s not strictly true. Roll20 offers a whole host of options for seeking players, joining groups and even hunting down Game Masters. Whether you’re a total newbie, an experienced dungeon delver or even a professional GM looking to get paid, you can put yourself out there and find a game to suit your tastes.

Let’s take a step back, though, and assume that you’ve never tried a tabletop RPG before. As discussed above, now is a great time to get involved, especially since they provide both entertainment and social interaction at a time when both are sorely needed.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Briefly, a tabletop role-playing game (RPG) is sort of the halfway point between a board game and an improvisational theater group. You and three to five of your friends pick a game — for example, Dungeons & Dragons. You create a character who inhabits this fantasy world, such as a clever human wizard, a brave dwarven fighter or a cunning elven ranger. One of your friends acts as the Dungeon Master or Game Master (DM or GM), who guides the rest of the players through a story. You roll dice to resolve any encounter that’s in doubt, whether it’s fighting off a horde of goblins, or talking your way past a recalcitrant town guard. The GM can buy licensed adventures from the RPG’s publisher, or create his or her own.

If it sounds complicated, try watching a session online, or playing in one yourself; you’ll “get” how it works within a few minutes. It’s basically a game of make-believe, but with rules and continuity.

In any case, if you don’t have a group, you can use Roll20’s Join a Game feature. If you do, you can dive right in and create an account. It’s a pretty standard username/password/profile setup.

Roll20 tutorial and basics

Whether you’re a GM or a player, you’ll still need to understand Roll20’s basic controls. Essentially, the program is a digital mapmaking tool, which lets you design areas on a grid, then move player “tokens” around them. If you just need to keep track of player location and combat distance, you could get by with a bunch of colored dots on featureless gray tiles. (I am not knocking this idea, incidentally; it saves a lot of work, and players are going to conjure up something elaborate in their imaginations, anyway.) You could also get artistic and deck out a map with gorgeous custom artwork, elaborate character models and complex level designs. Either way, the principles are the same.

While I can’t explain every feature of Roll20 (partially because there are a lot of features, and I haven’t explored them all yet), the built-in tutorial is a great place to start. The tutorial walks you through creating a map, adding character tokens, roll dice, program macros, add music to your game and so forth. Players don’t really need to go through the whole thing, but GMs should, particularly since part of the tutorial covers revealing parts of the map to players over time. (If players can see the whole map from scratch, it obviously spoils a lot of the surprises they’d find while exploring.)

Roll20 is a complicated program, and learning it requires a lot of trial and error, even with the long, complex tutorial. As such, some additional resources I’ve found useful are the Roll 20 Crash Course, as well as walkthrough videos from the Roll20 team. These include an overview of the toolkit, a brief video on designing maps, and a long, comprehensive walkthrough of the entire Roll20 system.

To give you the bare-bones version of what you’ll need to learn: Use the draw tool to design maps. Import assets into your art library for level features and character tokens. Move characters around the map. Program dice rolls for each character, unless you plan to roll in real life (and you trust your players to do so). Reveal the map as players encounter new territory. If you can do all of these, you’re at least 80% of the way there.

Furthermore, Roll20 has built-in voice and video chat. I’ve never found video chat necessary, and it can eat up a lot of bandwidth. Voice chat works well enough, although my groups still prefer to use Discord instead. If you find you don’t want the Roll20 voice chat, it’s easy enough to mute.

When to use Roll20 — and when not to

Having spent a fair amount of time in Roll20 over the past few weeks, I’ve found that it can enhance a tabletop RPG —but it can also drag the experience down. Just as you wouldn’t necessarily make a battle map and make your players measure their movement speed for every encounter in a game, you don’t need to play out an entire session in Roll20. (You can, but it’s exhausting for both the players and the GM.)

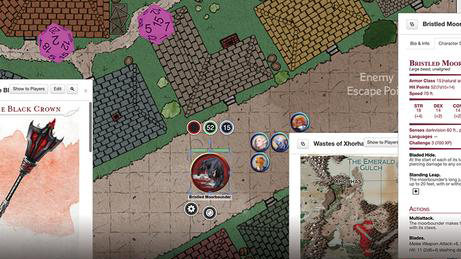

First off, you should use Roll20 for combat encounters. Positioning, environmental obstacles, movement speed and weapon ranges are all vital, and it’s extremely hard to keep track of all this in your head. (This is especially true since your conception of the battlefield may be quite different than another player’s.) If you suspect your players are going to get into combat in a certain area, you should design that area and populate it with the necessary foes. Even if they somehow bypass it, it’s better to be prepared.

On the other hand, you generally don’t need Roll20 for simple social encounters. If your party is wandering through a town, stopping in taverns and talking with a few characters at a time, Roll20 is not really going to add anything to the experience. You can design every tavern, shop and castle if you’re really into mapmaking, but functionally, there’s no purpose. It’s a lot easier on both you and your players if you stick to “theater of the mind” for most noncombat encounters. The same is true of traveling from place to place; it’s enough to say “you move through a forest” rather than making players drag their tokens across a mass of trees.

Of course, there are some marginal cases, such as scenes that involve extended skill checks, or social settings where positioning is extremely important. (Think about a chase through a crowded city for the former, or a fancy nobleman’s gala for the latter. These are just examples; they could be anything.) Generally speaking, if you think that you might need to roll dice to determine distance and movement, a Roll20 map — even a very simple one — could be a huge boon. The maps are not easy to design on the fly, so try to have one ready in advance.

Beyond that, a lot of Roll20 is trial and error, so go ahead and experiment with features like character sheets, system compendiums, mobile apps and licensed, purchasable content. Nothing is going to replace getting together with a bunch of friends to run a game in-person, but under the right conditions, Roll20 can come close.

Marshall Honorof is a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.