Air conditioner vs. heat pump: Which is best for your home?

Too hot? Here’s two alternatives for beating the heat.

Air conditioner unit outside

(Image credit: Shutterstock)As the dog days of summer start to growl and bite with temperatures pushing 100 degrees Fahrenheit, it gets harder to keep your cool at home. While air conditioners have been the go-to choice for decades, a newer technology — heat pumps — are starting to become more popular, as they can also pull double duty by heating your home in the winter.

While both air conditioners and heat pumps are electrically powered and are based on similar engineering, several key differences separate them. Here’s a look at how they’re alike, how they differ, and which might be best for your home.

How does an air conditioner work?

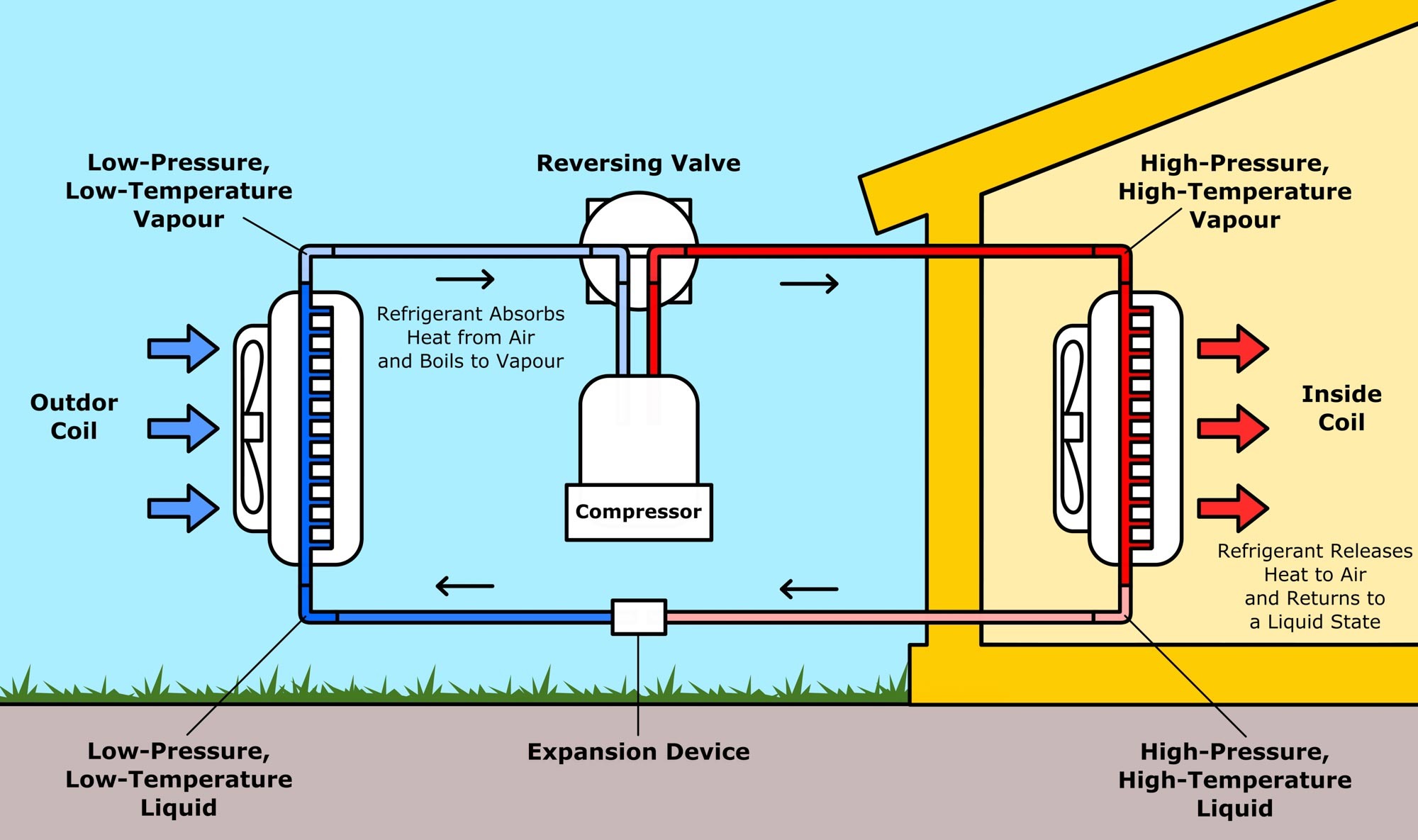

A traditional air conditioner has a closed loop of piping filled with a refrigerant that easily undergoes phase changes from a liquid to a gas and back again.

To cool your home, an air conditioner compresses the gas, and then allows it to expand. As the refrigerant evaporates into a gas, it lowers the surrounding temperature to something like 40 degrees Fahrenheit. This cooled gas runs through a series of metal pipes; the air conditioner then blows the cooled air over those pipes and into your home.

Plus, on a hot and humid day, the AC’s evaporator is generally well below the air’s dew point, the temperature at which water from the air condenses. In other words, an AC not only lowers the temperature but the humidity as well, making the room feel less damp and more comfortable.

How does a heat pump work?

There’s no thermodynamic free lunch; when an air conditioner compresses the gas back into a liquid complete the cooling cycle, it creates lots of heat, which a conventional air conditioner dumps into the outdoors through a radiator.

Heat pumps use this to their advantage. While they cool in a similar manner to air conditioners, they use the heat generated by condensing and compressing the refrigerant back into a liquid to keep the house toasty warm in the winter. In essence, a heat pump cools in the summer by delivering cold air from the hot outdoors and provides heat in the winter by moving heat from a cold outside. It might seem paradoxical, but it works.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

These days, heat pumps are available in a variety of shapes and sizes for windows, in wall installation as well as designs with separate evaporators and condensers. Some are even small enough to heat and cool electric cars like the Nissan Leaf or Tesla Model Y. The EcoFlow Wave 2 portable heat pump can even run on battery power for the ultimate in year-round glamping comfort.

Heat pumps seem custom made for areas that need cooling and heating. They’re popular from New England to the South to the Pacific Northwest with 16 percent of American homes using heat pumps. South and North Carolina lead the way with 46 percent and 42 percent of homes using this technology to heat and cool homes.

The challenges with heat pumps

It might be hard to imagine on a 90-degree day, but heat pumps have a serious gotcha when it gets really cold. As the mercury drops below zero Fahrenheit, a heat pump’s efficiency declines rapidly and can have trouble keeping up on a cold night. That’s why many heat pumps have old fashioned resistance coil heaters inside that kick in when the heat output lags, like a February morning in Grand Forks, North Dakota.

The other factor holding back widespread adoption of heat pumps is price. Owing to their relative novelty, they’re more expensive than traditional HVAC systems. For instance, I’m contemplating replacing the 15-year-old heating and cooling equipment for my 650 square foot basement, but the room would need an $800 15,000 BTU air conditioner to guard against the hottest summer day. By contrast, a $1,100 heat pump of the same capacity would cost $1,100. And while you can find both whole-home and split air conditioners and heat pumps, window air conditioners are far more common than window heat pumps.

Despite $300 price difference, the heat pump might be a better bet because it would also heat the room in the winter. Additionally, there are a slew of rebates and incentives available. Although some depend on your income, the inducements from local utilities, states and the Federal government, could come to $10,000 for a whole-home heat pump system.

Should you get a heat pump or an air conditioner?

Ignoring the financial inducements, the heat pump’s higher efficiency and all-season comfort could help the equipment pay for itself on its own. I’ll need to be patient, but the Department of Energy’s heat pump cost calculator estimates that an up-to-date Energy Star certified heat pump could save as much as 570 kilowatt hours annually in electricity. That’s about $140 a year in power bills for my area.

It adds up to a payback period of a little more than two years. That’s not bad, but over the equipment’s estimated lifetime, it could yield $1,890 in savings versus an AC unit. This means that the heat pump could pay for itself and give me a nice profit.

There’s a green payoff as well. By using less electricity, it can reduce my carbon footprint by an estimated 890 fewer pounds of heat-trapping carbon dioxide each year. That adds up to nearly five tons less greenhouse gas emitted over its lifetime.

Sure, heat pumps are a viable alternative to conventional air conditioning but are not for everybody. If all I cared about was the upfront cost, I should beat the heat and kick back with an inexpensive air conditioner. On the other hand, only a heat pump can warm and cool while paying me and the environment dividends, letting me chill while laughing all the way to the bank.

AC vs. heat pump: Pros and cons

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Air conditioners | Heat pumps |

| Pros | Inexpensive | Cools and heats |

| Row 2 - Cell 0 | Established technology | More efficient |

| Cons | Only Cools | More expensive |

| Row 4 - Cell 0 | Row 4 - Cell 1 | Newer technology |

More from Tom's Guide

Brian Nadel is a freelance writer and editor who specializes in technology reporting and reviewing. He works out of the suburban New York City area and has covered topics from nuclear power plants and Wi-Fi routers to cars and tablets. The former editor-in-chief of Mobile Computing and Communications, Nadel is the recipient of the TransPacific Writing Award.