Mojo AR contact lenses hands-on: A new way to look at the world

We had the chance to see Mojo’s AR-powered contact lenses in action. Here’s what to expect.

I'm staring straight ahead, going about my daily business, when suddenly it hits me that I should check for traffic on the way home. Without even breaking stride — or pulling out my smartphone — I flick my eyeballs upward until a little green dot appears, floating in front of me. When I stare at that dot, it expands into a pop-up window with a small, easy-to-digest list of routes home, and how long each one will take me. I can make that info disappear by looking away, without even turning my head.

This is the future that Mojo wants to bring us. And while the demo I'm experiencing is taking place courtesy of a virtual-reality (VR) headset, the startup has a much smaller computing device in mind — a contact lens that sits right on your eyeball and serves up contextual information as needed.

We're a way off from slipping on contact lenses capable of serving up augmented reality (AR): While Mojo has built a working model that employees of the startup have been testing around the office, there's still regulatory reviews by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to complete. That process is likely to take a couple years and even then, the first iteration of Mojo's contact lenses will likely be designed to help people with impaired vision. But the eventual goal is to create an AR-enabled product that anyone would be able to use.

"Ultimately, we want this to be something that any consumer would be able to to get and wear and experience," said Steve Sinclair, senior vice president of product and marketing at Mojo.

Mojo lenses: ‘Information you want when you want it’

Mojo's contact lens is based on the concept of invisible computing — "a platform that delivers the information you want when you want it but disappears the rest of the time," Sinclair said. Think of it as a different approach to what you're currently doing with your smartphone. That device requires you to stop what you're doing and pull it out and look at the screen to find the information you need – whether it's directions, upcoming appointments or playback controls for the songs you're listening to.

Placing that information on a screen that's always in front of you — like a contact lens directly in front of your eyeball — means that you don't have to stop what you're doing to look something up. And the minute you've got what you need, that information disappears.

"Our goal is to bring people's eyes up, to get them more engaged in the world around them, get their heads out of their screens, Sinclair said. "And to do that, counterintuitively, we're putting a display basically on the eye, because we want people to be engaged in the real world [and] bring up the information contextually that matters and then have it go away."

AR glasses and headsets were supposed to deliver the same experience, but even glasses that have been slimmed down since the awkward days of Google Glasses remain very noticeable, not just to people who wear the devices but to everyone around them. Speaking personally, the best part of any AR glass or headset demo I've experienced in the past five years is the moment that I can take that device off.

As something designed to be worn all day, Mojo's contact lenses are aiming for a different experience. "You put [Mojo lenses] on in the morning, take it off at night, and get value from it throughout the day," Sinclair said. "It's not intended to be 'I put it on and I do a specific task for an hour or two.' Then I get tired of it and I take it off."

How Mojo’s lenses work

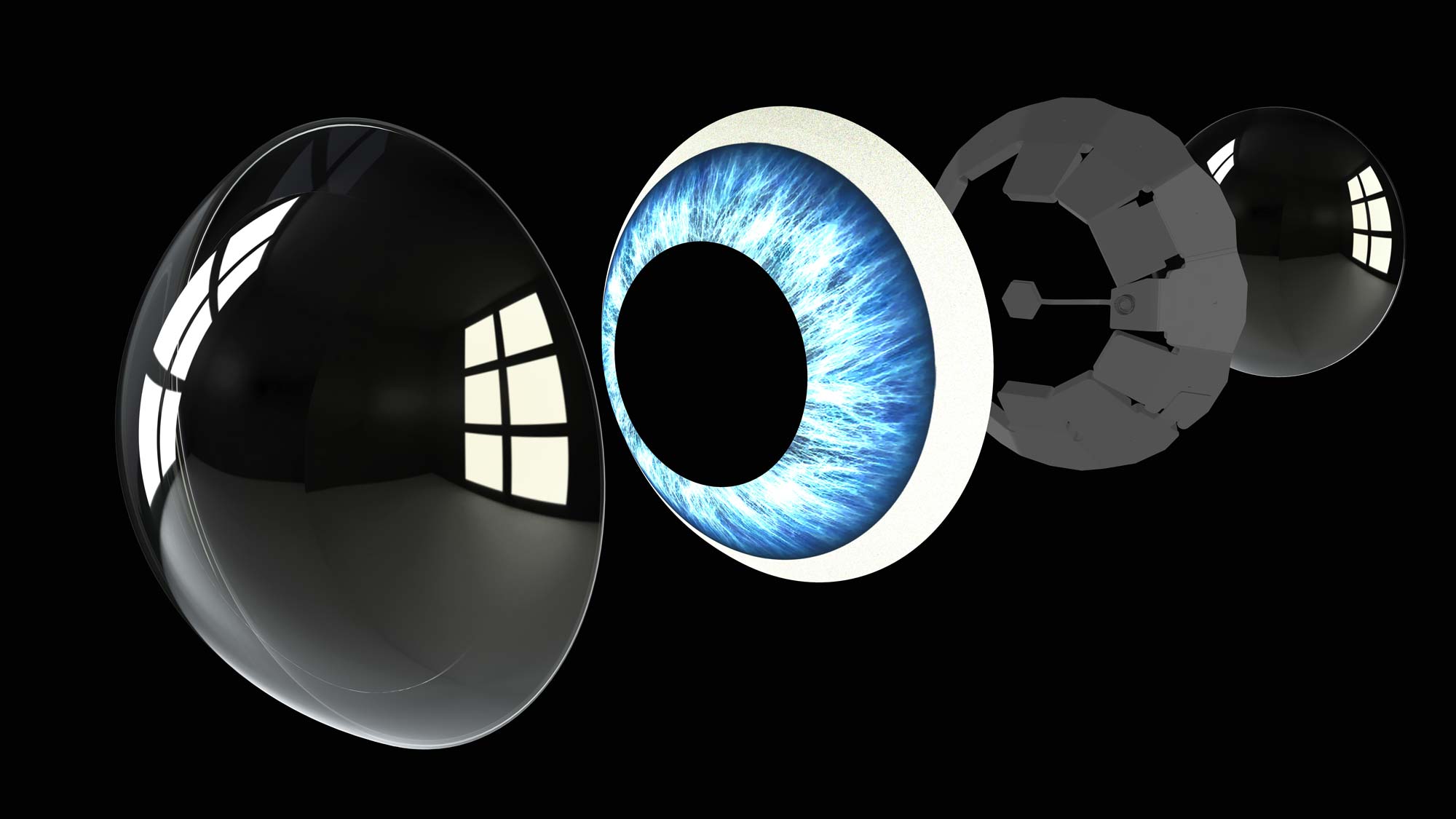

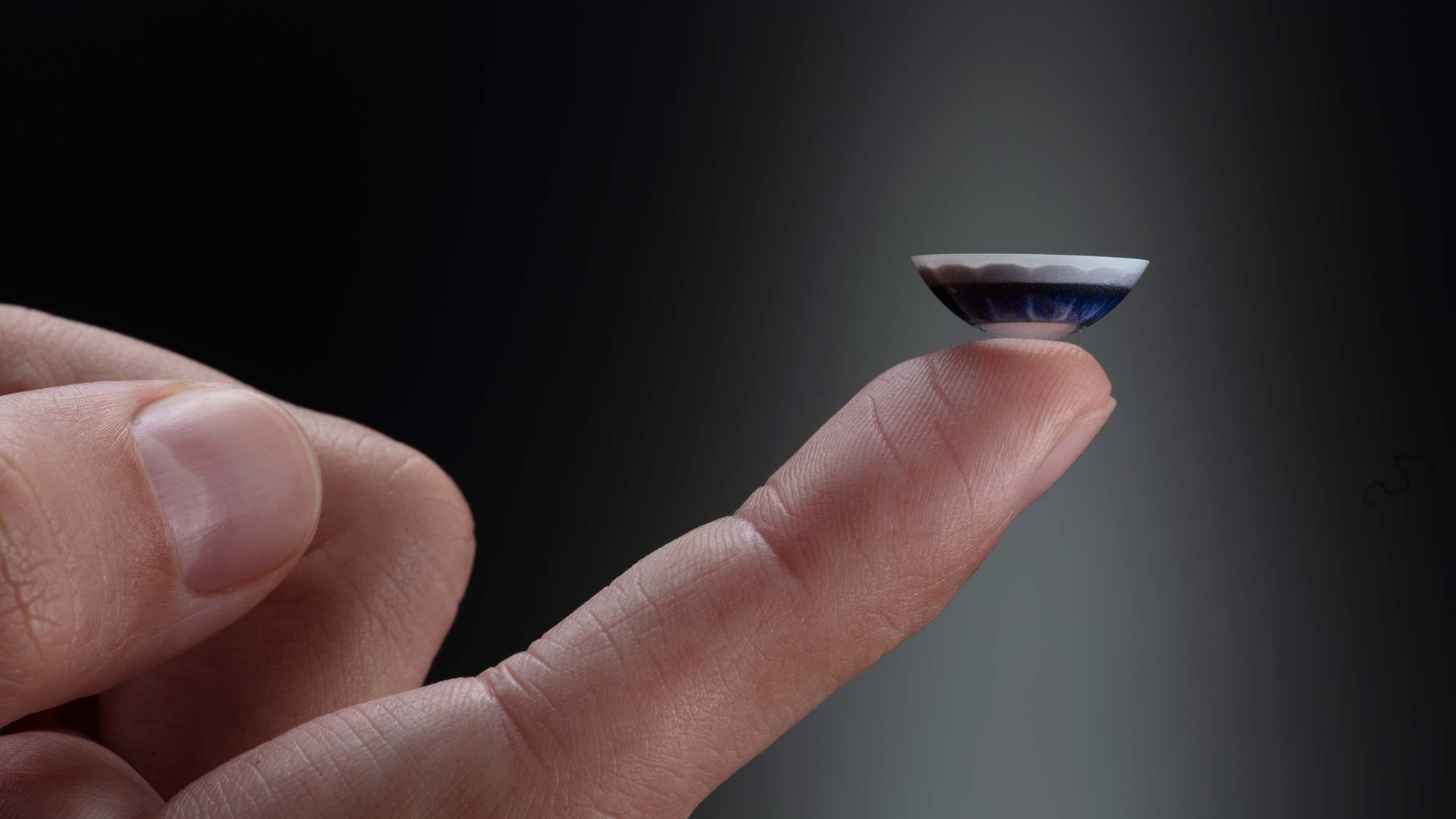

Unlike soft contact lenses that are made of flexible plastic, the Mojo lenses are rigid gas permeable lenses that rests on the sclera — the white of your eye — forming a vault over your cornea.

The lenses are specifically designed for the specific topology of the wearer's eyes. That way, Sinclair said, they don't rotate or slip during the day, keeping the display embedded on the Mojo lens pointed at your fovea, where the center of your field of vision is found.

This required customization explains why the demos I used at Mojo's Saratoga, Calif., headquarters featured VR headsets and exterior lenses, rather than the extensive fitting needed for a pair of contact lenses.

The Mojo lens features a built-in display and is currently powered wirelessly, though the plan is to eventually add a small battery onto each lens itself that will provide a day's worth of power. (Since you'd take out the lenses at night to sleep, that's when you'd charge them.) The lenses are worn in both eyes, so that the augmented image on the display –– like the traffic and weather information I was able to summon on Mojo's demo headset –– appears in 3D, floating in front of you.

The current version of Mojo's lenses feature oxygenation, which allows the company's employees and testers to wear the lens for extended periods. (Sinclair says it's quite comfortable.) The future version, in addition to adding a battery, will have a higher-resolution display, motion sensors for tracking eye movements, and an image sensor that can see what you're seeing, for computer vision purposes. In other words, the lenses will be able to recognize the objects you're looking at and bring up contextual information.

The Mojo lenses will connect wirelessly to an accessory you wear near your head, Sinclair said, and that device will be tethered to a smartphone that pulls data from the cloud — most likely over 5G by the time the Mojo device is ready — that's transmitted to the display in front of your eyeballs.

"Once we have all those pieces together, then we have the full system," Sinclair said.

Mojo lenses in action: What are the use cases?

What Mojo has in place now is a series of demos that give you an idea of what to expect once the contact lenses are publicly available. In one demo, I held up a lens as close to my eye as possible and looked through it. I saw a black-and-white display superimposed on a screen, showing data like a timer counting down, the speed of a bicycle going by, and the heart rate of someone exercising. (This kind of data hints at some of the information Mojo believes its contact lenses can serve up in specific-use cases, like athletic training.)

The demo showed images on an 8,000-pixels-per-inch (ppi) display; a second-demo showed off how a 14,000-ppi display might look. That's the goal Mojo is working toward with its contact lenses, and the demo images are noticeably sharper.

A third demo of Mojo's contact lenses illustrated how they could be used to help people with impaired vision – by creating an overlay of the surrounding world. I stood in a pitch-black conference room where I couldn't even make out my hand in front of my face. Holding up the Mojo lens to my eye, though, caused the display to tap into near-infrared technology that displayed the outlines of road signs and even people.

"We give people superpowers in this case," Sinclair said.

It's easy to see how such a product could help someone with diminished vision, whether it's due to glaucoma, macular degeneration or some other condition; this accounts for the FDA's interest in what Mojo is working on. Seeing outlines of signs and other objects could help someone move around safely and independently.

Mojo lenses: Looking beyond health

Sinclair and other executives at Mojo see potential uses beyond just health-related ones. The ability to see clearly, even in low-light, could help security guards in dark environments, whether at a concert venue, bar or just a facility that needs guarding after dark. And that's the next step in Mojo's evolution, even as it pursues medical uses for its AR-powered contact lenses.

"We are looking at enterprise applications and vertical applications where we can see immediate use for something like this," Sinclair said. "A lot of those fall into any situation where someone needs to do a job where they have a customer service or customer-facing element to their job where they want to look normal, like they're not wearing gear [and that lets them] get the information that's useful to do their job and allows them to be hands-free."

That will mean opening up the Mojo contact lenses to app makers so that they can create software that works with the company's heads-up display.

Mojo lens concerns: Distractions, doctors visits and privacy

It’s one thing to fill up a smartphone screen with a lot of detail, but a display for a contact lens requires focusing on pertinent information that doesn't distract the viewer.

"We have to be really careful and design very well for this idea that it is persistent information that can be on over your eyes, and to not add to distraction but actually build a system that helps with distraction," Sinclair added.

Other issues will need to be addressed as Mojo's contact lenses go through further development. Because the lenses will need to be fitted to your eyeballs, that will require a prescription and a visit to the optometrist — not necessarily a bad thing from Mojo's perspective, though it could limit widespread adoption as the contact lenses branch out to wider-use cases.

Also, there's the issue of privacy, and how much of the data that flashes across the contact lenses' displays will be for your eyes only. That object-recognizing image sensor, for example, could raise concerns that the people you're looking at are being photographed without their knowledge or consent, though Mojo stresses that its sensor will be used for computer vision purposes only, not for snapping photographs that are shared or circulated.

"We know that if we want to do something developed on the premise of invisible computing that privacy has to be key," Sinclair said.

Outlook

But that's a few years off. For now, the work at Mojo is going to focus on efforts to shepherd the contact lenses through the FDA-approval process now that the basic idea behind these AR-powered devices looks solid.

"We're wearing them. We see content. We know that it's not a matter of if now, it's just a matter of when and proving the safety and efficacy so the FDA certifies it," Sinclair said.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Philip Michaels is a Managing Editor at Tom's Guide. He's been covering personal technology since 1999 and was in the building when Steve Jobs showed off the iPhone for the first time. He's been evaluating smartphones since that first iPhone debuted in 2007, and he's been following phone carriers and smartphone plans since 2015. He has strong opinions about Apple, the Oakland Athletics, old movies and proper butchery techniques. Follow him at @PhilipMichaels.