AI image generators need just 200 sample images to perfectly recreate an artist style — here's how

If imitation is the best form of flattery, where does that leave AI?

Recent research from the University of Washington and the Allen Institute for AI has shed clearer light on the reality of our new world of AI and copyright.

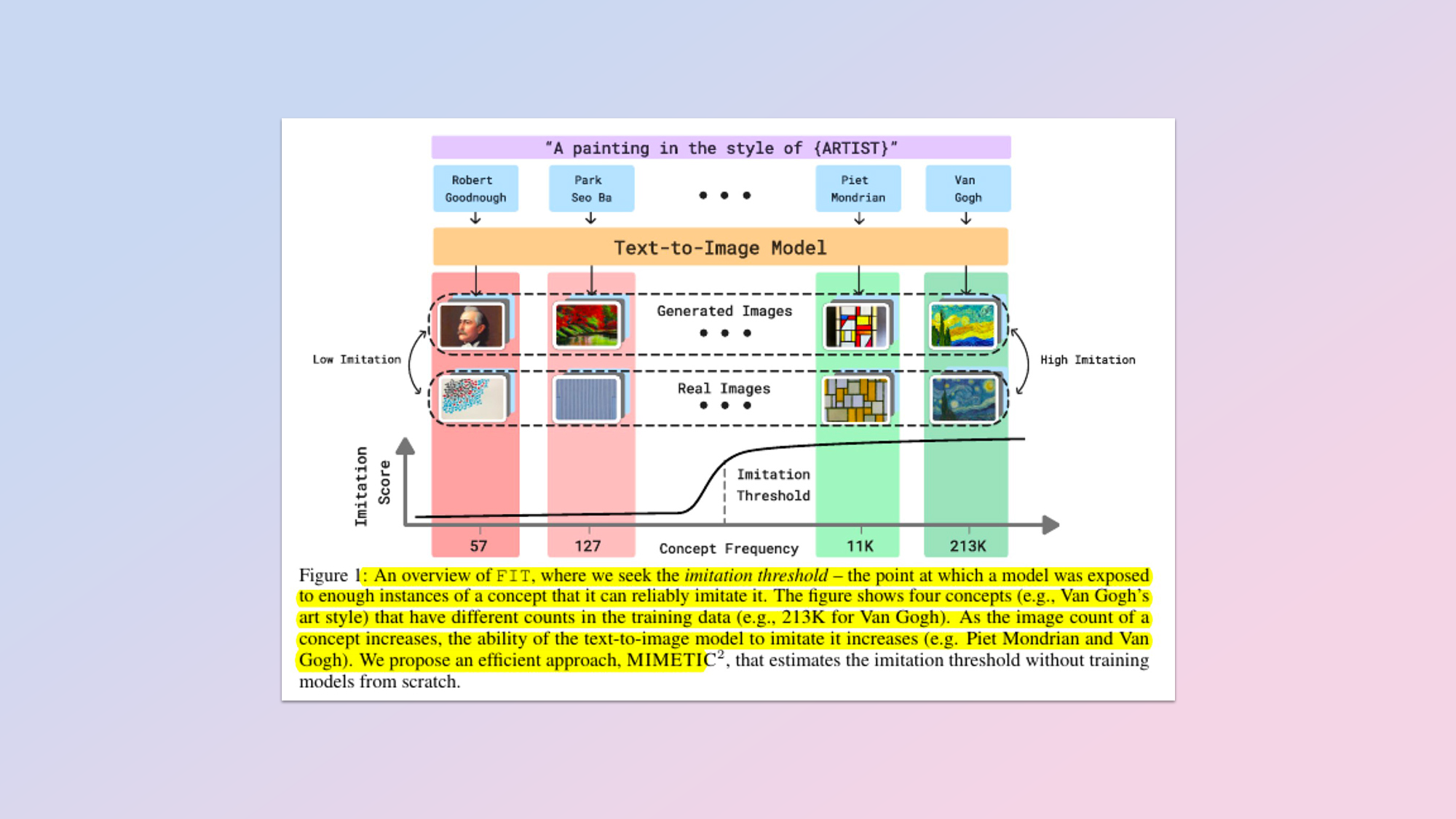

The Study, titled How Many Van Goghs Does It Take to Van Gogh? Finding the Imitation Threshold, suggests there’s a specific threshold that is important for determining when an AI model is effectively copying a likeness.

The research focused on two main domains, human faces and art styles, which are two of the most contentious parts of the AI copying controversy.

The researchers found that the point at which a model could replicate something from its training data was surprisingly low, at just 200 to 600 images. In other words, show an AI model around 600 images and it will probably be able to recreate it perfectly.

This has deep implications for the future of AI training because it should give developers a benchmark to aim for, and so save huge sums of training money going forward.

What are the implications of the study?

The other huge implication of this study relates to copyright infringement. Text to image model makers can now point to the research as a proof point against copyright claims if they can show that their model was subject to a smaller number of training exposures, say 100 or so.

“The imitation threshold can provide an empirical basis for copyright violation claims and acts as a guiding principle for providers of text-to-image models that aim to comply with copyright and privacy laws.”

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

By encoding AI imitation into a specific formula like this, dubbed MIMETIC2, courts and privacy advocates will be able to use this as evidence of whether or not an AI was capable of imitating a piece of work, or whether the training threshold was not reached.

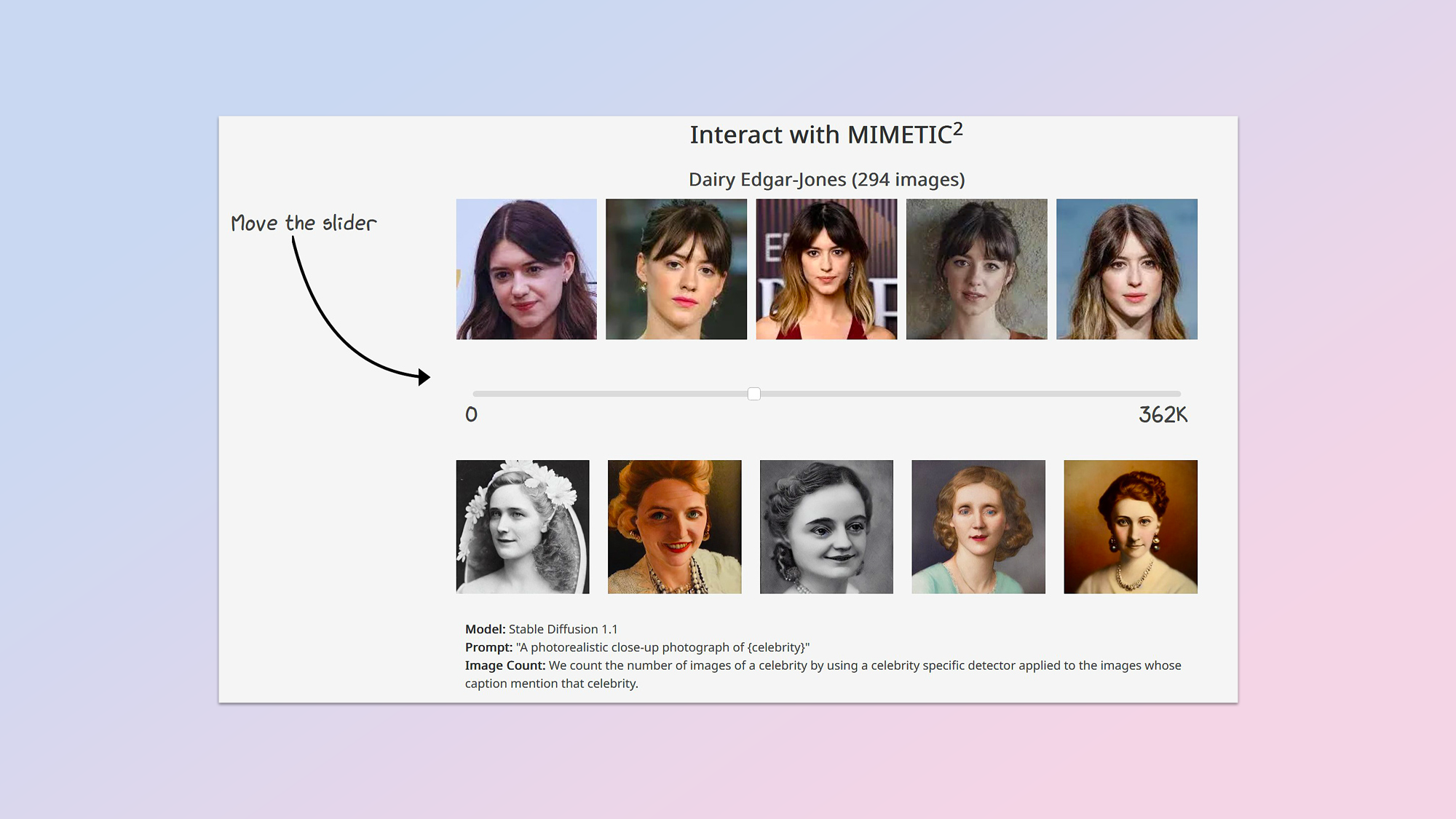

As part of the study, the team has produced a live imitation evaluator, which is available on its Github page, which demonstrates the formula in action using a slider and real person images.

The mockup demonstrates that any number below around 450 images produces severely distorted AI imagery, while above 600 the imitation became significantly stronger - until eventually the similarity is clear and obvious.

You can almost hear lawyers around the world rubbing their hands together in anticipation of juicy future fees.

So this solves the copyright issue?

The reality may not be quite so clear as it seems. The major copyright defense currently being lined up by the AI titans is a universe away from scientific formulas and academic research. The key question their lawyers are asking is, does an AI company have the same rights to enjoy fair use as human beings?

It’s long been established that anyone, especially students and academic organizations, can rely on the doctrine of fair use when replicating original forms of media such as art and photography.

How else can a student learn if they can’t copy an artistic style, and learn what makes certain brushstrokes and color combinations so powerful and compelling?

Similarly, students of photography are deliberately trained in the style of iconic photographers, like Cartier-Bresson, Adams and Leibovitz, in order to properly learn the use of tone, lighting and composition.

AI models, the argument goes, are doing nothing more than these students when they are being trained. They are ingesting the foundational aspects of the art, and being taught how to use those features to create new and original works worthy of their own status.

The fact that an AI can deliberately or inadvertently mimic a famous artist of history, is no different to the many students who deliberately copy significant styles in homage to legends of the past.

What happens next?

The core principle in this kind of copyright question has always been that imitating a style is not copying. Styles are something which are free from restraint, and producing clever academic formulas is not going to, or definitely should not, change this paradigm.

The result could be a world where any form of artistic study, style experimentation or innovation is sued to extinction. Copyright was never designed to stifle artistic development or cultural respect.

The research team itself acknowledges some of the limitations of the study. Imprecise labeling (e.g. calling a Rembrandt, a Van Gogh), images with multiple subjects, and general factors such as resolution and even diversity all have an impact on the quality of the final scores.

It may be unwise for us to assume anything about their future capabilities right now. As scary as it sounds, this is a story which is only just beginning.

So basically this may not be the complete answer the world is hoping for. For example how good does a reproduction have to be before it can be considered ‘infringing’. Does a terribly composed imitation of a Warhol classic count?

These questions and many more will no doubt be exercising AI lawyers and pundits for the next decade at least, during which time we’re going to see the kind of technological advances which may make it all irrelevant. At what point does any of this matter, if an AI of the future can produce original works which are so sublime that all historic work pales in comparison?

We’re a mere two years into public exposure of the power of AI artistry, and right now we’re watching a toddler learn how to metaphorically hold a paintbrush. Two years ago AI systems were thought to have an equivalent human age of around 7 years old, now, their developers are tagging them as teenagers. AI is growing up fast.

It may be unwise for us to assume anything about their future capabilities right now. As scary as it sounds, this is a story which is only just beginning.

More from Tom's

- I can’t wait for artificial intelligence to take this job away from humans

- I test AI for a living and these are the 5 most amazing AI tools of the year

- Anthropic just published research on how to give AI a personality — is this why Claude is so human-like?

Nigel Powell is an author, columnist, and consultant with over 30 years of experience in the technology industry. He produced the weekly Don't Panic technology column in the Sunday Times newspaper for 16 years and is the author of the Sunday Times book of Computer Answers, published by Harper Collins. He has been a technology pundit on Sky Television's Global Village program and a regular contributor to BBC Radio Five's Men's Hour.

He has an Honours degree in law (LLB) and a Master's Degree in Business Administration (MBA), and his work has made him an expert in all things software, AI, security, privacy, mobile, and other tech innovations. Nigel currently lives in West London and enjoys spending time meditating and listening to music.