Ad Block Apocalypse? Here's How to Save the Web

Ad blockers are endangering the web's revenue model and over 230,000 jobs. Can users be convinced to unhide the ads? Will lawsuits help? How about anti-blockers? We look at five ways publishers are fighting back and whether they are working.

Pop-ups. Streaming commercials that autoplay with sound. Animated banners sitting next to the text of your favorite articles. It's no wonder that an increasing number of Web users are installing ad blockers, which remove all advertisements from the page to deliver a clean and hassle-free reading experience. According to an August report by PageFair, a company that tracks the phenomenon, nearly 200 million Web users run ad blockers.

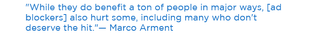

However, most Web publishers rely on advertising fees to keep the lights on, and PageFair's report estimates that blocked ads will result in $21.8 billion of lost revenue this year alone, a number it expects to nearly double in 2016, particularly with Apple recently adding ad-blocking capability to the iPhone and iPad. That also means potentially hundreds of thousands of lost jobs and the end of the free Web as we know it.

Content creators, advertisers and even ad-blocking companies are hard at work, looking for ways to save the Web publishing industry. Their efforts fall into five main categories: lawsuits, moral suasion, improved ad quality, anti-blocking software and new revenue streams (native ads, e-commerce, paywalls). Just how bad is the problem of ad blocking and can any of these methods combat its dangerous effects?

Web Becoming a Walled Garden

Without Web advertising, those publishers who survive will either put up paywalls on their sites or move content onto platforms where ad blockers don't work, such as mobile apps or Facebook's Instant Articles program. In either case, publishers will lose a lot of money and eyeballs as their articles live in walled gardens like iOS apps.

Users who run ad blockers may be inadvertently helping one ad company win out over another. While enabling ad blocking in Safari browser, Apple has not allowed it to disable the iAds that it serves in mobile software.

"Who's going to make all that content we love so much, and what will it look like if it only makes money on proprietary platforms," The Verge Editor Nilay Patel asked in a recent article.

230,000+ Jobs in Danger

"While it is not evident that it is costing jobs today, we believe that in the future add blocking could be a seismic event within the digital media ecosystem and if left unchecked could drive quite a few publishers out of business," said Ben Barokas, CEO of Sourcepoint, an anti-ad blocking software vendor.

It's impossible to figure out exactly how many jobs will be lost or never created because of ad blocking, but our back-of-the-envelope calculations equate the $21.8 billion loss in 2015 with approximately 230,000 jobs. We base this on an average compensation of $89,000, which we get by averaging the average salaries of Web-publishing-related jobs (developers, writers, IT managers, designers) as listed on Indeed.com (NYC area) and deducting a 5 percent profit margin. Globally, average salaries are probably lower and other expenses detract from the total.

MORE: Is Ad Blocking Stealing?

Is Ad Blocking Wrong?

"Stealing content has become effortless, which is likely why so many consumers have a false sense that it isn't stealing at all. The same mentality applies to thinking that ad blocking isn't a problem." That's Rob Rasko, an IAB executive adviser and CEO of the 614 Group consulting firm, writing in an article on Marketing Land. "When you visit a site, that publisher has a right to show you an ad in order stay in business. It’s that simple."

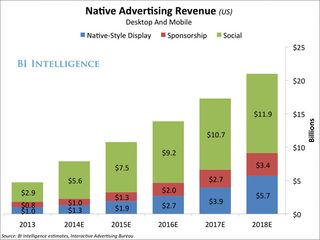

Developer Marco Arment seems to agree. A couple of days after releasing the Peace ad blocker, which was briefly the No. 1 paid app in Apple's App Store, he decided to pull it down, citing a crisis of conscience. "Ad blockers come with an important asterisk," he writes on his blog. "While they do benefit a ton of people in major ways, they also hurt some, including many who don't deserve the hit."

However, some professional ethicists don't see it that way.

Jack Russell Weinstein, a University of North Dakota philosophy professor who runs the Institute for Philosophy in Public Life, argues that there's no implied agreement between readers and publishers not to block ads.

"Seeing ads is not 'the price we pay' for visiting a website, in part because prices are a negotiation," he writes. "There is no negotiation with Web traffic; there is no actual communication."

Business ethicist Chris MacDonald, a professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, agrees, arguing that "the relevant property rights are not well established. Users don't invite advertisers to invade their screens, so in the absence of some clear tradition or law, they may well be justified in kicking the invaders out."

Coming at the question from a utilitarian point of view, Cyberethicist David Whittier told Digiday that "ad blocking is completely ethical because it by far benefits more people than it harms." However, he doesn't explain why the benefit of avoiding annoying ads outweighs the downside of losing the free, open Internet and putting hundreds of thousands of jobs in danger.

"Online advertising is really the price we pay for a so-called 'free' Internet," business ethicist Emmanuel Tchividjian, an SVP for PR firm Ruder Finn, told Tom’s Guide. "I believe most would agree that in a 'cost-benefit' analysis, the annoying distractions of online ads are well worth the Web content we enjoy."

Solution 1: Moral Suasion (aka Please Whitelist Us)

One possible way to limit ad blocking is through moral suasion. If users believe that their actions are harming people's livelihoods and endangering the free content they enjoy, perhaps they will voluntarily uninstall or never install the blockers. For more than a decade, music and movie industry groups have run massive consumer-education campaigns explaining the problems with illegal content downloading. In 2007, Universal Music Group created a series of posters showing disembodied eyes, fingers and ears with the tagline "Stop destroying the band you like. Say no to music piracy."

While Web publishers haven't united against ad blockers, a number of sites, including Wired and New Grounds, a gaming site, have posted messages imploring their readers to whitelist them. The Washington Post recently put up a message, requiring users to sign up for its newsletter if they run ad blockers and want to view the content.

So far, such appeals have fallen on deaf ears. According to PageFair, just 0.33 percent of ad- blocking users whitelisted a site after seeing an appeal from the publisher asking them to do so. Of those users, a third eventually un-whitelisted the site.

What are readers thinking? In the case of music piracy, consumers seem more concerned with danger to themselves or their reputations than with the potential harm they are doing to content providers. A 2007 study of college students who download illegal music found that increased threats of negative consequences (fines, jail time, lawsuits) were effective in curbing the behavior but raising awareness of the damage done to artists and record companies was not. However, researchers found that subjects were less likely to pirate songs when they thought that their peers would perceive it as wrong.

"The use of social norms as a disincentive to download music may be particularly effective for certain consumers," Aron M. Levin, Mary Conway Dato-on and Chris Manolis write in the Journal of Consumer Behavior. They then suggest that the music industry run PSAs similar to those that have been effective against underage drinking and smoking.

In order to use social norms to stop ad blocking, publishers must convince readers that this behavior is unethical. As we've seen, not everyone agrees on this point.

Solution 2: Lawsuits

The Record Industry Association of America (RIAA) made headlines in the late 1990s and early 2000s when it sued music sharing services like Napster and drove them out of business. Could publishers or advertisers sue the ad-blocking companies and win? Don't count on it.

AdBlock Plus prevailed this spring in two different German lawsuits brought by publishers. In both cases, the courts ruled that the software company did not violate anti-competition laws by asking publishers to pay for inclusion in its whitelist and did not violate copyright by helping users remove ads.

So far, the issue hasn't been extensively litigated in the U.S. or other parts of Europe. However, David Moore, the chairman of the IAB Tech Lab's board of directors, told Ad Age that "there is work being done to explore" the trade group's legal options and whether they could sue a blocker.

The IAB would probably have an airtight case against ad blockers . . . if it sues in China. In August, a Shanghai court ordered the makers of MoreTV, an app that shows video streams from other sites, to pay 100,000 yuan ($15,610) in damages to iQiyi, a popular content site whose content was shown with the ads removed.

Solution 3: Better Ad Standards, Less Annoyance

Along with asking users not to block their main source of revenue, everyone from advertising groups to the ad blockers themselves is trying to improve the quality of ads and get rid of the worst offenders.

"You cannot really stand over a claim that you're doing all you can to survive and please, buddy, switch the ads back on," said PageFair Innovation and Systainable Media Leader Johnny Ryan. "The industry needs to start looking at how it advertises."

The Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), a leading trade group for advertisers and publishers, recently launched its Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG), which is working to combat malware and fraud in ads. In August, the trade group released a new set of proposed guidelines that prioritizes the user experience and urges adoption of HTML5 over flash.

"The entire supply chain in many ways bears the burden of reconciliation here from marketers, and anyone who's creating advertising and publishers to help solve these problems," said Scott Cunningham, IAB's vice president of technology and ad operations.

Perhaps surprisingly, Eyeo, which makes and distributes the popular AdBlock Plus suite, also wants to help improve the quality of ads. The company has created a program it calls the "Acceptable Ads Initiative," which whitelists certain publishers or ad networks, as long as they meet certain standards, such as avoiding pop-ups, ads that cover content and blinking animations.

"Once you click on the ad, it can do anything it wants. The reader didn't necessarily ask for the ad to take over the screen. I think It's about engaging with them on a level where they're not intruded upon," said Ben Williams, the company's operations and communications director.

The Acceptable Ads Initiative has generated some controversy because Eyeo charges larger publishers ─ those who need to unblock over 10 million ad impressions per month ─ to stay on the whitelist, a practice some publishers consider extortion. Williams wouldn't disclose the amount of money companies pay, but said that it is generally a percentage of the revenue they see on the unblocked ads.

Though Eyeo has created its initial standards by surveying users, Williams said his company wants to work with publishers on a set of guidelines that balances marketers' needs with users. "We're trying to invite more people under the tent," he said.

PageFair also wants to bring publishers, marketers, even ad blockers and users together to agree on better ad standards.

"Now we have to think about advertising 2.0 and the people who need to lead that discussion are publishers," Ryan said. "We’re having round tables now with the leading publishers globally and we are trying to start a conversation that questions what isn't acceptable. Is it OK for someone to take data from your reader? Is it OK for an ad to jump around the screen? If it isn’t, then say it now."

Unfortunately, none of these efforts to improve advertising on the Web addresses one of the reasons why ads have become so obtrusive ─ the need for direct response. Where advertisers in television, radio, print and outdoor signage are usually more than happy to get a broad message across, online marketers usually measure success in immediate interaction. If a click or a sale is your primary success metric, your incentive is to do anything you can to grab attention. With more places to advertise than ever, publishers aren't in a strong position to set the rules of engagement. It can't help, though, when sites place dozens of ads on the same page.

"If you look at some sites if you have AdBlock Plus on, you'll see the ad counter rack up to like 25 or 30," Williams said. "If you're an advertiser on that site, you have a 1/30th chance of being the brand that the person sees and that's not too good. So if I'm a brand, I'm like, 'Get me out there, bigger than the other guy.'"

The ad improvement solution assumes that users will agree to stop using ad blockers or whitelist sites voluntarily. If publishers decide to run fewer, less-obtrusive ads, there's a good chance that the 198 million ad blocking users won't even notice. Eyeo's Acceptable Ads Initiative whitelist is enabled by default in AdBlock Plus, but users can turn it off and AdBlock Plus is just one of several blocking applications.

And even if ad standards improve across the board and everyone knows it, users may just prefer an ad-free experience.

"Users will not uninstall ad blockers full stop," Barokas, the Sourcepoint CEO, said.

Solution 4: Anti-Blocking Software

A few companies offer anti-ad blocking software that's designed to get advertising through the filters so users see it, even if they are running a blocker. PageFair delivers non-obtrusive ads that get through the filter, while Sourcepoint gives publishers the choice of delivering a non-obtrusive ad, trying to get the same type of ad past the blockers or offering an ad-free subscription.

However, the companies that make the blockers aren't standing still, either, as they undoubtedly modify their software to get around the anti-blockers. Anti-blocker companies will then update again. It's an arms race.

Publishers also have the option of removing all the content when someone visits with an ad blocker on. Moore told Ad Age that, at a recent IAB summit, he "advocated for the top 100 websites to, beginning on the same day, not let anybody with ad blockers turned on [to view their content]," but members failed to heed his call.

Perhaps these sites are worried about alienating users who, even if they are blocking ads, still contribute to their total audience metrics and drive potential revenue through e-commerce links or native advertising, both of which make it through the filters. In 2010, Ars Technica briefly hid content from ad block users but turned the feature off after just 12 hours and a lot of angry comments. In a post, Editor-in-Chief Ken Fisher described the content-hiding as "an experiment gone wrong" and concluded that periodically asking readers to whitelist the site should take the place of blocking the blockers.

It almost goes without saying that the three largest companies that make browsers and operating systems could put an end to ad blocking tomorrow if they wanted to. If Apple, Google and Microsoft programmed Safari, Chrome and IE / Edge Browser not to work with ad-blocking software, few users would run it. However, two out of three are doing just the opposite with Apple adding Ad Blocking capabilities to iOS 9 and Google listing ad blocking plugins in the Chrome Web Store. More than half of all ad blocking users ─ 126 million of them ─ are on Chrome, according to PageFair's report.

Solution 5: Native Ads / E-Commerce / Subscriptions

Though traditional banner and text ads make up the lion's share of revenue for most publishers, there are a few blocker-proof ways they can earn revenue today.

Native advertising is the practice of including promotional units in the site content, without sending them through an ad server or often making them look like ads. Advertorial articles are a common form of native advertising but so are paid results in a site's internal search engine and ad units that appear as story listings in a site's content feed (perhaps on the home page). If properly labeled, these custom promotions provide a unique and immersive way to weave advertising into the fabric of a site.

However, the best native advertising is customized by the publisher and pitched directly to the marketer. That type of manual effort won't scale as easily as running standard-size ads through trafficking software and may not even be possible for smaller publishers.

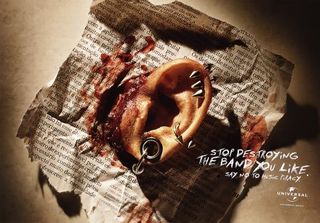

While growing, native promotions make up only a fraction of the ad market. According to a May report from BI Intelligence, native revenue for 2015 accounts for $10.7 billion, a fraction of the estimated $170 billion digital ad market, of that, only $3.2 billion is sponsored content or display advertising, the kind that most benefits Web publishers.

E-commerce referrals to vendors like Amazon and NewEgg also provide a way for content sites to pay the bills. However, not every topic lends itself to product recommendations and not every reader is ready to buy something every time he or she visits.

Subscription revenue sounds like an appealing solution, but few have been able to make a lot of money from it. The New York Times is one of the most successful sites with a paywall, but it has only 1 million digital subscribers out of the 57 million visitors it gets each month [].

Bottom Line

Though Web publishers have other ways to make money, advertising remains the key revenue driver for most and will be for the foreseeable future. If ad impressions continue declining due to ad blocking, many online media companies will go away, taking jobs and the open Internet with them — along with a lot of great stories.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.