Full-Scale USS Enterprise Will Take $1 Trillion to Build

An anonymous engineer has figured out how to build a real USS Enterprise that could trek to Mars in 90 days.

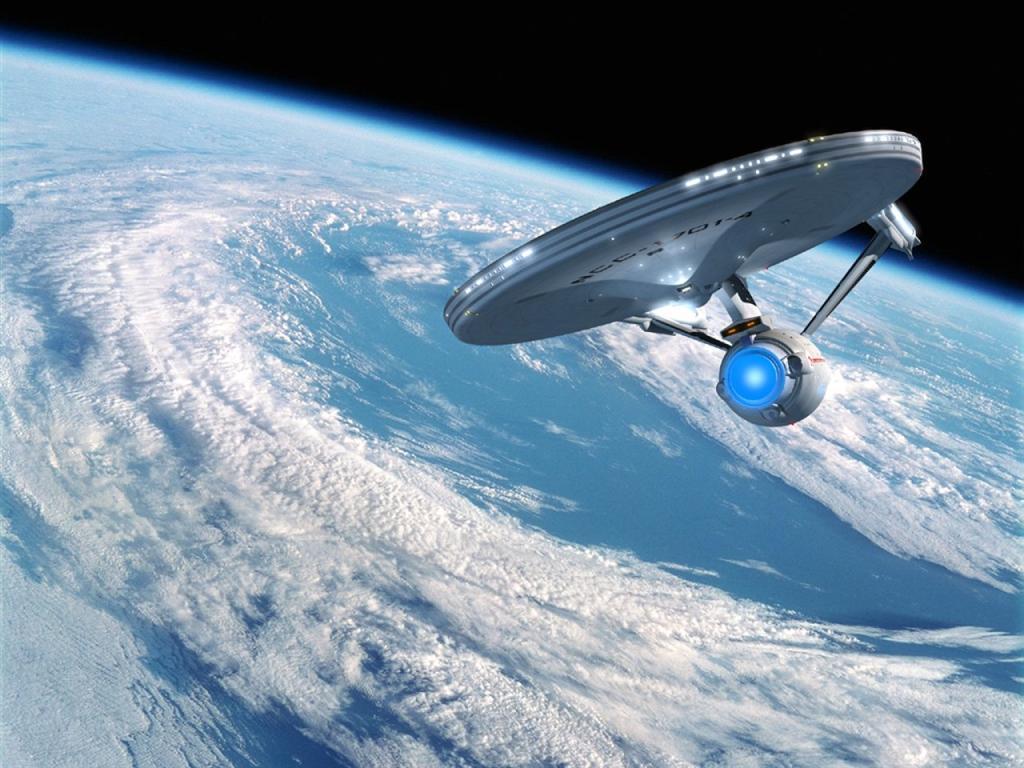

An anonymous electrical and systems engineer -- we'll call him Scotty -- has determined that by using today's technology, it would take $1 trillion and 20 years to build a working USS Enterprise that could travel to Mars in 90 days. Even more, the saucer would support 1g of gravity so that the crew wouldn't float around and banging heads. Its length from the front of the saucer to the rear tip of the nacelles would be 960 meters -- twice as long as the former World Trade Center towers were tall.

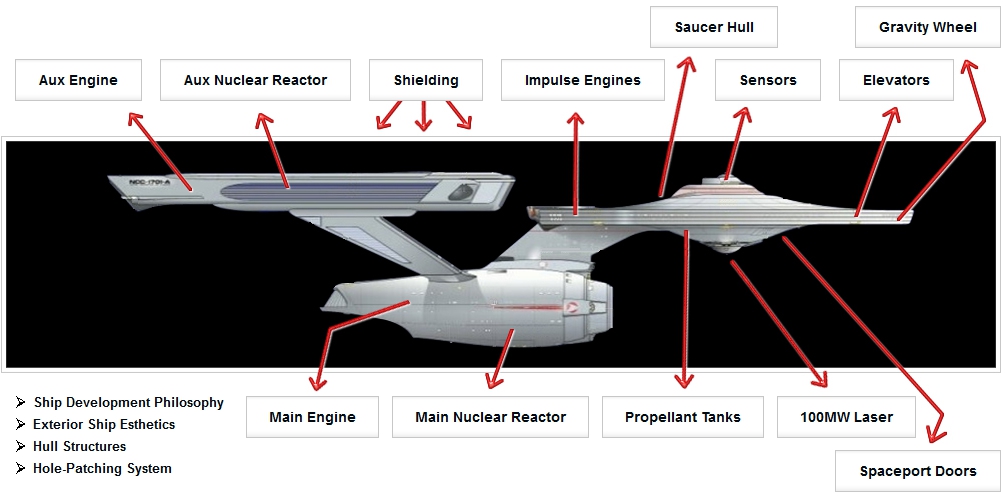

"The Gen1 Enterprise will be powered by three ion propulsion engines," Scotty writes on his dedicated website, BuildTheEnterprise. "These will provide constant acceleration, and versions of this technology are already used in spacecrafts. These engines are powered by electricity, and thus using nuclear reactors to generate this electricity is a natural fit."

According to his diagram, the ship will come packed with a laser mounted in or near the dome located at the bottom center of the saucer hull. The laser output power goal will be 100MW which could be sustained for at least one minute. This laser, the most powerful ever that could achieve a sustained output, would be powered by the electricity generated by the main 1.5GWe nuclear reactor mounted in the main body of the ship. But there's a drawback to using this proposed weapon.

"When the laser is on at full power, the main engine must be shut down since there is not enough electrical power generated by the main reactor to power both the laser and the main engine," he writes. "The laser will generate a lot of waste heat since the process of converting electrical power into light power is not 100% efficient. The aluminum outer surface covering the hulls of the Enterprise will act as a radiator to radiate heat into space and prevent the ship and the laser itself from overheating while the laser is on."

The engineer's diagram shows that the spaceship will have three primary ion propulsion-type engines (or ion thrusters): the main engine which will eject "thrust" out the former shuttle bay opening, and an auxiliary engine in each nacelle. "The thrust created by an ion propulsion engine is very small compared to conventional chemical rockets, but these engines have a very high specific impulse, meaning they use propellant very efficiency," he explains. "This high propellant efficiency is achieved by accelerating the propellant to very high speeds."

The saucer will be where the crew will live and perform their duties. It will be 1500 feet in diameter (.28 miles) and 75 feet thick around the perimeter -- near the center of the saucer hull it grows to 300 feet thick. It will also house a magnetically suspended gravity wheel that will be sealed in a donut-shaped cavity lined around the interior perimeter. It will generate 1g of gravity inside the interconnected pods that make up the gravity wheel, but all other locations inside the ship will not have gravity.

Compared to the fictional Enterprise ships, the proposed real-world version is somewhat bigger -- the USS Enterprise NCC 1701-D was 642.51 meters. There are a number of reasons for this: it needs to house a gravity wheel large enough in diameter so that the gravity seems reasonably Earth-like. It needs to be a hybrid, serving as a spaceship, a space port and a space station supporting up to 1000 crew members at any time (the 1701-D supported up to 6,000). It also needs plenty of cargo room to haul probes, landers, and base-building equipment to Mars and elsewhere.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom's Guide direct to your inbox.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

"Simply put, if we want to get serious about establishing a permanent human presence in space, with robust and sustainable capabilities to do big things up there, we need a big ship," Scotty writes.

Out of the twenty-year construction timeframe, nine will be dedicated to research while the remaining eleven will be actual development including hauling the parts into space, piecing it all together, testing the systems and performing a trial run to the moon in three days. And given that it won't give off any warp signatures, there's a good chance the Vulcans will just drive on by and not give the flying monkeys another glance.

Kevin started taking PCs apart in the 90s when Quake was on the way and his PC lacked the required components. Since then, he’s loved all things PC-related and cool gadgets ranging from the New Nintendo 3DS to Android tablets. He is currently a contributor at Digital Trends, writing about everything from computers to how-to content on Windows and Macs to reviews of the latest laptops from HP, Dell, Lenovo, and more.